They might be 68 years old collectively, but I’m not one for the “retro-test” sign. These “Bumers” are still going strong, hitting the road almost every day and delivering on their promise. Think about pleasure? Absolutely, they deliver that too. Three brothers, three legends, three moods—or three diagnoses of BMW?

Picture this: it’s eight in the morning, minus ten on the thermometer, and we’re on the empty roads of the test track, with snow, ice, and powdered asphalt. It’s March sixth, the perfect petrolhead spring. In the E39, the contact is somehow inadvertently lost somewhere in the speed sensor circuit, and the stability system off lamp lights up on its own. Need more hints?

“Three-thirty,” “five-thirty,” “seven-forty”—music in numbers. Riding in such company is already a holiday, but seriously imagining a comparative test between them, agree, is difficult, because these sedans have always been not competitors, but a gang from the same yard. Moreover, these models were produced for a very short time, from 1995 to 1998. But in my opinion, that time was the zenith of the classical, crossover Bavarian triad, and after twenty-something years, the E36, E39, and E38 “threes”, “fives”, and “sevens” became classmates of the “necropremium” segment—and this is already a reason to clarify relations.

There is another reason. There are now 312 thousand kilometers on the odometer of my “thirty-nine”, and a similar number I will see on the calculator if I dare to calculate all my expenses for a year and a half after purchase. Considering that I myself drove only 15 thousand kilometers, the average money outlay per hundred slightly does not fit reasonable norms, so sometimes I still wonder—was it worth disposing of these funds a little more rationally? For example, to buy the E36 or E38. In general, you all understood correctly: I just took advantage of my official position to close the winter season on legendary cars and once again check the correctness of my choice.

BMW 740iL (1999)

Time is the best critic. Put the E38 next to the “sevens” of all subsequent generations and say who among them is a true aristocrat. This design is eternal. Cars from the E65 and even F01 projects today already find it difficult to hide their age, while the E38, like Dorian Gray, only gets better with age. It is sad that since then BMW has not been able to release a more elegant large sedan. Chris Bangle is often blamed for this (the E38 was one of the last projects completed before the arrival of the American chief designer), but the direct author of the masterful silhouette, the Austrian Boyke Boyer, remained the chief exterior designer at BMW for a long time and retired only in the mid-2000s. It’s not just about people. The entire concern at the end of the 20th century changed priorities in favor of engines that needed more air and more space. The hood line rose, followed by an increase in roof height and the level of the stern, and as a result, we now have the G11 series flagship, which even in the base version, the 730i with four cylinders accelerates faster than the dazzling “seven-forty” from the 90s.

But the E38 shines with a low silhouette (lower than that of the modern third series) and exemplary proportions. And you haven’t even seen the BMW 740i in the M Sport version, with 180,000 kilometers, which my friend Georgiy restored to collector’s condition. I dreamed that this car would participate in the test, but almost all Russian “sevens” in a condition close to ideal share one thing—they don’t leave the garage in winter, or even in summer in bad weather. So welcome another “seven-forty”—slightly dulled luster and a mileage of 215 thousand kilometers, but in the extended version and without signs of “do not touch with hands”.

Stretched BMW 740iL is 100 mm longer than the base sedan. The chances of finding a functional “seven” are slightly higher among those “il” that worked in corporate parks and were well serviced.

About the interior of the E38, the well-known blogger Doug DeMuro once said, “Behind the wheel of this car, you feel like the director of a company who is going to the office to fire a subordinate for stealing paper clips.” I would add that at the same time, you’re wearing a broad-shouldered double-breasted jacket, baggy trousers, and a tie with cucumbers. Some might argue that the jacket must necessarily be burgundy, but personally, the “new Russian” image and the “seven” are not synonymous—it’s the foam of the days, almost washed away by time—and the feeling of “oversize” from the 90s is still alive.

A quartet of dials, orange backlighting, a sprawling console — timeless classics. Just like the sense of quality in the “thousand little things” such as velvet inside the door pockets, but the flagship status against the “five” is expressed solely in size.

The interior of the E38 boasts the same impeccable and timeless details as my E39 “fifth series”. It’s just that the armrest is wider, the deflectors are larger, the handbrake is in a different place—and there are slightly more buttons on the central console. For example, here, separately, not only the temperature is regulated, but also the speed of the airflow in the right and left zones, and in richer versions, there were also massage buttons. But there are almost no visible attributes of luxury.

The similarity of the interior can be explained by the fact that the “seven” and the “five” were developed on the same platform and were released with a one-year difference. However, this also indicates that BMW engineers were primarily concerned with the driver’s experience, rather than flashy displays of opulence. Although when it comes to the driver’s experience, I would say this: the E38 is like the E39 on vacation.

The sporty nature of the E38 likely set it apart from its contemporary competitors, but today it’s just a serene sedan with smooth responses and a fairly soft suspension. Thanks to the fat winter tires 235/60 R16 for comfort, but the rolls and slight sway—it’s probably in the genes. The stability is still excellent, although the steering wheel is unexpectedly long—almost four turns from lock to lock—and during lane changes, the “seven” feels a bit sluggish.

I also came to realize that the 740iL version is the minimum living space for the E38, and this may not be the happiest news for vintage car hunters. Sedans of this generation were produced from 1994 to 2001, with ten different engine variations, including the first diesel “sevens,” but the mainstream options were the naturally aspirated V8 gasoline engines. This BMW 740iL, released in 1999, came after the facelift of 1998, which brought narrowed headlights, reconfigured taillights, DSC, side airbags in the basic equipment, and most importantly—a new 4.4 engine instead of the four-liter “eight”. The power almost remained the same (286 versus 282 hp), but aluminum-silicon alloy liners and the famous VANOS mechanism on the intake were introduced.

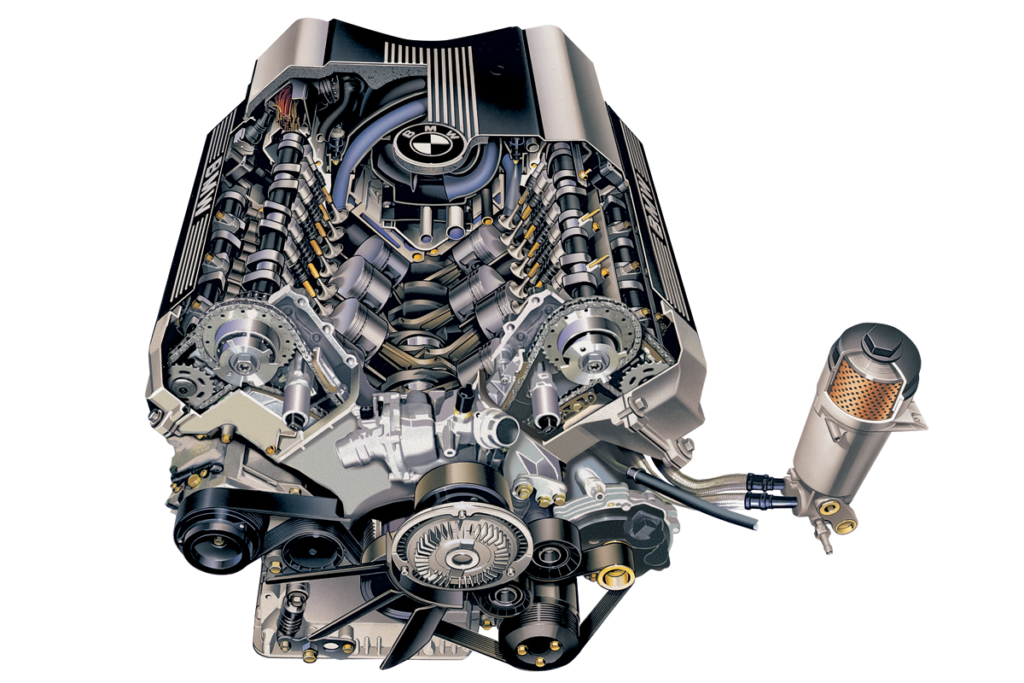

In 1992, BMW returned to V8 engines after a quarter of a century and encountered maximum bumps. Alusil, mass replacements of M60 engines under warranty, and the rushed launch in 1995 of the improved but no less controversial Nikasil V8 M62, which in 1998 also received the VANOS mechanism in M62TUB44 versions (pictured).

In good condition, this engine promises almost two-ton “seven” energy and acceleration to “a hundred” even better than my E39 530i—6.9 seconds. Although in reality, both the acceleration rate and the sharpness of the accelerator are perceived as more subdued. The thrust increases smoothly, without a sharp pickup, the sound is noble yet restrained, and animal instincts remain dormant. Boniface on vacation.

This, I repeat, if the engine is healthy. If not, it’s easier to find a new Boniface from Japan for 150-200 thousand rubles. Otherwise engine overhaul will cost almost twice as much.

I’m also skeptical about old cars with “automatics”: the ancient transmission most of all reveals the age of the technique and more often hinders communication with the old-school motor than provides comfort. In the case of this “seven,” the logic and speed of gear changes seem to be in order, but there are already jerks, and it’s unclear how much pleasure you will lose in the next shift. With a “manual,” everything would be simpler, more spirited, and cheaper, especially since the E38 is the last “seven” with manual gearboxes. Although where can you find one now?

In short, my initial impression of the “seven-forty” wasn’t too impressive, but then I drove it first on a serpentine road, and then on ice… Listen, it’s just a turn fighter. Well, a bomber-interceptor. Despite weighing in at 1964 kg with half a tank, there’s slightly less than 51% of the mass on the front axle. On a mountain road, the E38 effortlessly thrusts its nose into the turn, draws an arc, and rushes to complete the turn under the pull. However, when the rear slides, you need to steer a lot and with anticipation, taking into account the size and mass.

With such a combination of comfort and handling, the E38 is perfectly suited for the role of a Sunday family youngtimer. Indeed, in this capacity, it spent almost a year with its owner, but soon after this test, it was sold for 420,000 rubles. Someone got a very decent specimen. Although I don’t regret that it wasn’t me. I take off my hat to the “seven” as a work of art—the E38 is the only one of this BMW triad that can claim collector’s value in the future. Of course, to achieve this, you need to invest another three to four times the price of the car, but we are still talking about a budget of around two million rubles, in which Octavia or Camry, of course, look like a much more reliable investment, but only if the residual value is all the emotions you expect from a car.

BMW 320i (1995)

A living BMW E36 for three hundred thousand rubles—that’s a yeti. A legend. Many believe, but no one has seen. So feast your eyes on a true miracle, because the light-purple sedan, released in 1995, was bought three years ago for only 225,000 rubles. Plus tickets to Chelyabinsk and a car carrier to Moscow. So, for the half a million that my E39 cost, could I have also gotten a spare “thirty-sixth” for parts?

Arithmetically—yes, but in reality, solving such a problem will take an eternity. There won’t be more phenomena like the E36, because they have already been bought up by automotive journalists.

The thirty-sixth youth of this model flared up three years ago. It all started, of course, with Melnikov, and now among my friends-colleagues, I know at least five adepts. Although Vladimir himself recently sold his BMW 325i: he says he’s tired of it and outgrown it. These cars are passed from hand to hand, cherished, and generously fertilized. Especially beautiful is the story of the “three,” which was built by the racer Sergei Udutov, probably familiar to you from participating in several of our “ring” tests—let him tell it from firsthand experience. But personally, I’m more interested in this budget “three twenty” from the garage of former Avtorevyu advertising director Nikita Sitnikov. A whole car—for the price of repairing the E39.

Such horses don’t look a gift in the mouth. Or rather, they don’t look at the color of the interior or even at the engine displacement. If the sills and PTS are in place—you should take it. For what?

The “threes” of this series stand out among BMWs of the 90s. The E30/E32/E34 grouping was a mafia in Italian suits. The population of E38/E39/E46—careerists. And the E36 is just an alien, starting with the unique platform and ending with design details. For example, doors that go onto the roof have never appeared in BMWs again. Just like Saab-like deflectors around the dashboard.

In the base configuration, the steering wheel does not adjust for reach or even for height—and it’s strongly turned to the left, although sitting is still comfortable. The seat is low and holds tight, the transmission lever moves crisply. But the mood here is set by the first response to the gas pedal. What a personality has gone!

The “golden age” of BMW also includes crooked steering wheels, strange color schemes, and ergonomic quirks. Automatic air conditioning — with knobs, climate control — with buttons.

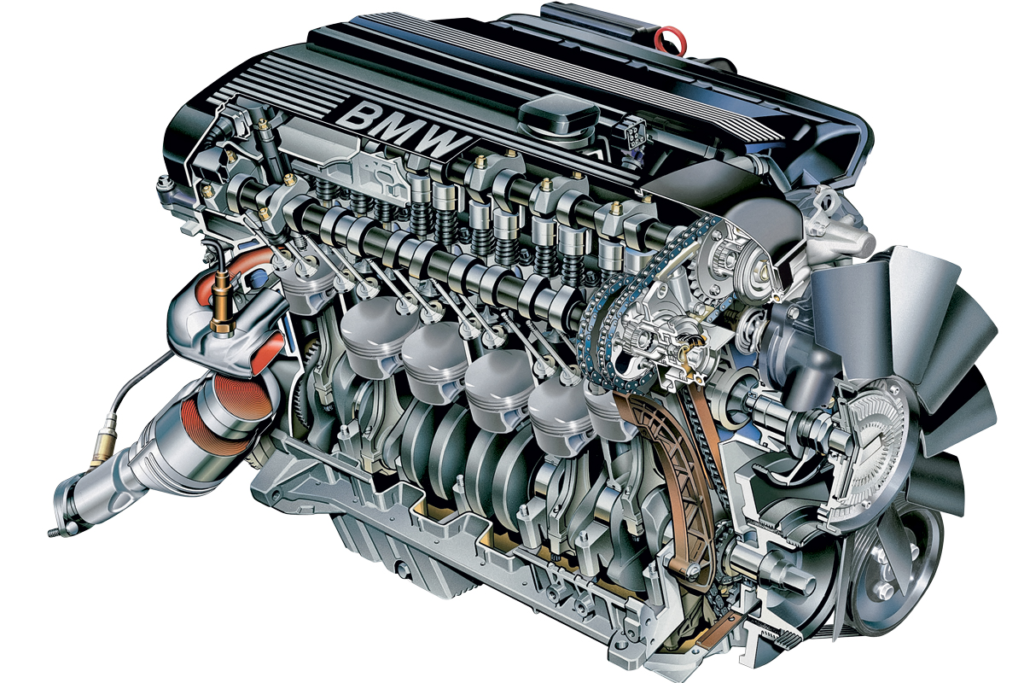

Six cylinders for two liters. Once, engines in this configuration were made not only by BMW but also by Alfa Romeo, Honda, Ford, Mazda, Renault, and even Nissan. But only at BMW, the cylinders were in a row and sounded like an orchestra. The “single-nozzle” aluminum engine M52B20 develops 150 hp, however, the sedan in the standard configuration on the scales showed 1345 kg, that is, the power-to-weight ratio is at the level of the Vesta Sport. But what a sensitive accelerator, what a bright pickup after 3500 rpm—and what a voice. Unlike the “seven,” the acceleration here is perceived brighter than it actually is.

Non-standard Koni Street shock absorbers made the “three” stiff, but did not change the DNA—50.3% of the mass is on the rear wheels. It seems that the E36 simply doesn’t know what understeer is, and on a winter road, it goes sideways both when reducing and when adding gas. The steering mechanism is “long” (3.5 turns from lock to lock), however, there is no feeling that you are wrapping yourself around the steering wheel, shifting the car from slide to slide. On the contrary, you want to steer more and more because there’s a natural effort under your fingers, which always makes it clear what’s happening under the front wheels. It seems I’m in the cult now too.

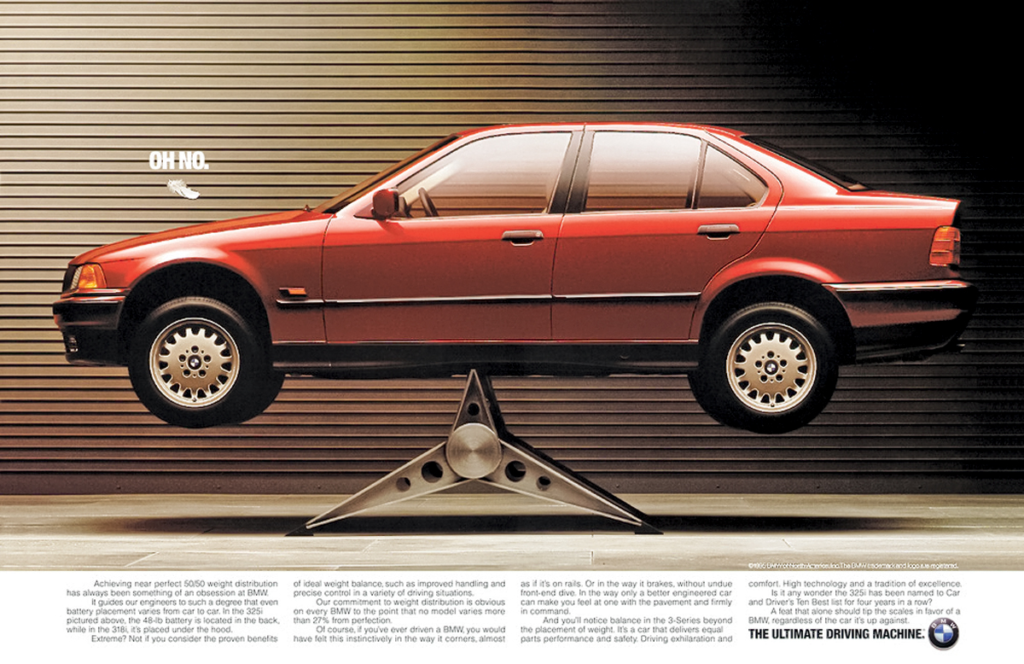

One of BMW’s many famous ads about the perfect balance of the E36. For this, the BMW 318i had the battery under the hood, and on the BMW 320i and 325i — in the trunk.

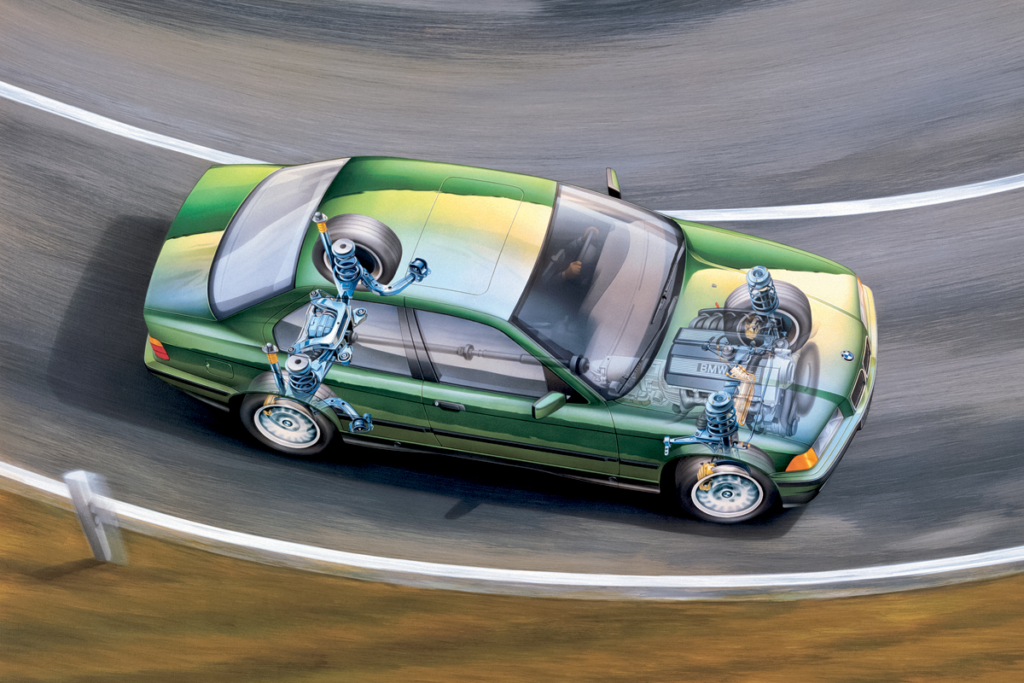

It’s no wonder that it was the three-link concept from the E36 in the 90s that served as the basis for the rear suspension of the new Mini and is still used to this day, even though the third series itself has long since changed its scheme. A phenomenal chassis. The world champion in figure skating.

The E36 “three,” along with the low-volume Z1 roadster, pioneered the new rear three-link suspension with a longitudinal trailing arm. The design was inherited by the next third series (project E46), as well as the new Mini, Rover 75, the first-generation X3 crossover (E83), and the BMW Z4 of the first two generations (E85 and E89).

Or rather, the champion’s simulator. Driving it every day is noisy, cramped, pitiful, and unsafe, and to become a true sports projectile, the “three twenty” lacks power, limited-slip differential, and a safety cage. But ask Sergey Udutov about the road to perfection, and the true greatness of the “three twenty” today is that at the price of a Lada, it is a car with a capital “B.”

In 1992, BMW discontinued all-wheel drive on the “threes” and “fives,” so all E36, E38, and E39 models were exclusively rear-wheel drive. Versions with “xDrive” returned to the third series only after the release of the X5 in 2000.

BMW 530i (2001)

Let’s not deceive ourselves; I expected my E39 to be the golden mean, the perfect mix of the excitement of the “three” and the comfort of the “seven.” But in reality, it turns out that the “five hundred thirty” is made up of two unequal halves.

The first is the M54B30 engine. And at twenty years old, it’s still a hurricane. Mathematically, 231 hp on 1631 kg is almost equivalent to today’s BMW 530i. But the surge of torque after 4000 rpm is spectacular, and in this aspect, the “five hundred thirty” is more thrilling than many modern cars. However, here I’m slightly cheating. One of my acquaintances reprogrammed the throttle control program, removing the dampers that BMW installed for the sake of ecology and comfort. This doesn’t change the engine’s external speed characteristics; it just makes the pedal sharper in the first part of its travel. It’s more fun in the city, making throttle blips easier, and the main surprise is the reduced fuel consumption to 11.5 liters per hundred kilometers. However, even with the reprogrammed accelerator, the “five hundred thirty” is less sharp than the E36.

I’m pleased that over the year and a half and 15,000 kilometers, the engine hasn’t presented any fundamental problems, except for the thirst for a liter of oil every 3000 km and hydraulic shock. Wait, haven’t I told this story? Oh, it’s worthy of a separate episode.

In general, the engine is the soul of the BMW 530i, but its body lives by its own laws. The smoothness of the ride and the handling of the E39 are much closer to the “seven” than to the “three.” I had no doubts about the comfort: soft, quiet, cozy. The roll wasn’t a surprise either, but it turns out that the E39 is the most front-heavy BMW in this company: 51.1% of the mass hangs on the front axle. And this is despite the fact that my originally “automatic” car now drives with a lighter “manual” transmission, and at the rear, on the contrary, a limited-slip differential has been added.

One percent is 16 kg. It may seem insignificant, but on a serpentine road, the front end goes out first, and what E36 does naturally, E39 requires effort. Before a slippery turn, you need to position the car with throttle or a shift; it doesn’t willingly turn into the corner on its own. But here the powerful engine and limited-slip differential come in handy, and when the angle is already set, the “five hundred thirty” steers more reliably and faster than the “three twenty.”

Was it better before? Yes, there’s soft plastic even under the handbrake in the “five,” and front headrests with electric drive, but the manual gearbox has a maximum of five gears, the side airbags are still in the form of “sausages,” and navigation maps for expensive versions took up to eight compact discs.

I’m often asked if it’s worth buying an E39 as a winter car. So, in summary—it’s worth it, but with three conditions. Firstly, a manual transmission to help with traction—both when inducing and controlling a slide. Secondly, good tires. At the beginning of this winter, I swapped worn Pirellis for new studded Continental IceContact 2s, which grip great on both snow and ice, are good on asphalt, and don’t lose studs, although I’m not being gentle. Well, and the third condition is a limited-slip differential. In the case of the E39, this is only available aftermarket, but without it, in my opinion, it will be boring and unsafe.

Unlike the preceding E34 “five,” standard “thirty-nines” did not come with a factory differential lock (just like the six-speed manual, which was only for the “M”), but it’s precisely the self-locking differential that makes the BMW 530i a vivid winter car — both in terms of driving experience and off-road capability.

And what to do in the summer? Last spring, I had a ready answer to this question—look for a new suspension, with which the E39 will ride tighter and more composed. For example, the BMW M Tech II kit, which came on the “fives” with an M package—or something from tuning kits. But the pandemic prevented the realization of that plan, and now I’m not so sure about the original idea. A new factory suspension will cost about as much as an E36, but it’s unlikely to turn the E39 into a comfortable “three.” So, maybe instead of a summer suspension, a summer car? Or still tuning? Okay, Bimmer, it seems I need another test.

Hydraulic shock laborer

The “five” with the atmospheric M54B30 engine mixes joy and pain much like gasoline mixes with air. Its design is a splendid illustration of how German engineering genius helps you find troubles out of nowhere and gracefully gets you out of them. All novices of the E39 movement know two main buzzwords when dealing with the “five” — “rust” and “engine rebuild.” But there’s a third one — “drainage.” That’s life. I learned about it last summer.

If the drains are clogged, rainwater from the windshield doesn’t drain into the wheel arch but starts accumulating in the tray to the left in front of the engine shield, where, by a stroke of luck, the brake booster is located. On a twenty-year-old car, the “booster” doesn’t guarantee sealing, so when the “bath” fills at least halfway, the vacuum starts sucking water inside. The sloshing under the brake pedal is easy to miss when starting off, and then it all depends on the owner’s luck. If it’s not great, you’ll accelerate nicely, hit the brakes — and BMW will avenge Stalingrad by directing a stream of water straight into the intake manifold. Hydraulic shock guaranteed even on dry roads.

And if the karma is okay, then you, like me, will simply slow down before a speed bump near the store — and the engine will stall at idle. The diagnosis will be the same in both cases — water in the cylinders — but the consequences will be different. I got away with a “flooded” throttle and washed compression. The connecting rod-piston assembly of the M54 engine withstood the hydraulic shock without consequences for geometry and without emulsion in the oil. The “five” started after drying the cylinders and still flies to this day. The repair, new booster, system bleeding, and brake disc replacement as a bonus cost 30,000 rubles. But the experience is priceless. I’m sharing it — check the drains.

Georgy Balabadzhyan

Georgy Balabadzhyan

It’s amazing, but the E38 “sevens” on the secondary market in Russia cost as much as in Germany and much more than in the USA. However, this doesn’t mean it’s easier to find a car here. Fans of the “sevens” here are divided into those looking for a copy of the BMW from the movie “Bimmer” — and everyone else. Moreover, there are plenty of daring sedans “black on black” for every taste and budget. But I was looking for something else and fruitlessly monitored the market for many years.

By the way, it’s surprising that with such a number of E38s for sale, they are almost non-existent on the roads—mostly they are used on weekends or sit in garages.

In the end, I bought my short “American” BMW 740i, produced in 2000, in Armenia with a mileage of 175 thousand kilometers. A rare color, Stratus Metallic, with a light interior (only about five hundred restyled “seven-forties” were made in this color). An equally rare M Sport package includes Sachs shock absorbers and a Shadow Line kit, foldable seats, and much more. The body is in perfect condition, as is the engine and automatic transmission — thanks to the years in California. And the price is only $7500. But this is just the down payment on the “youngtimer mortgage.”

Due to the California heat, the interior dried out along with the seals, the moldings deteriorated, and the headlights became cloudy. I’ve been working on this car for exactly a year, and to bring it to the desired condition, I’ve already spent about 1.5 million rubles. And that’s almost without bodywork. The money went to new optics, small decorative elements, interior trim, wheel restoration, missing fasteners, and other little things. By the way, many parts are already out of production.

It will get even worse next. After all, this is an expensive high-class car — and the prices of spare parts correspond. Moreover, it’s a very complex car with lots of electronics and sophisticated solutions. Restoring each function is a whole story.

Investment potential? A well-maintained, well-preserved, or restored example will appreciate over time — possibly even by an order of magnitude. But among the whole variety, the most valuable will be the BMW Individual versions in rare color combinations. It’s precisely these that are worth investing time and resources into — definitely not the “black Bimmers.”

I don’t expect great financial results; I just enjoy it. And by the way, that’s why I don’t drive it in the winter: I spent a whole year restoring the “seven” to its beauty, and snowdrifts, slush, and dirty feet in the light interior will ruin all the magic. A “seven” in the mud is violence against beauty.

Sergei Udotov

Sergei Udotov

If BMW had made this sedan themselves, it would be called the M316i, but they didn’t, so my friend and I took on the task. It all started two and a half years ago when we bought a green “three” for 220,000 rubles. The idea was to build a beautiful classic car capable of enriching the bloodstream with gasoline both in the city and on the racetrack. We looked at several “thirty-sixes” and were horrified: replaced panes, rotten sills, holes in the floor. But one day, among this raw material, we found a pleasant four-cylinder sedan BMW 316i in the most basic configuration with a mileage of 200 thousand, but without any signs of rust and almost entirely in the original paintwork.

To fulfill our vision, we promptly acquired an M52B28 engine (2.8 liters, 193 hp), subframes, brakes from the E36 M3, a differential with a lock, wiring, brake lines, and various other components. Despite the master’s assurance of a two-week completion timeline, the project extended to six months. After approximately one thousand kilometers, the engine overheated on the service center’s premises following a thermostat replacement—thus, the cycle began anew. With parts, a rebuild amounting to 150,000 rubles, and more waiting ensued. The BMW, now a 328i, performed admirably. We even triumphed on the Moscow drift track several times, showcasing the car’s ability to gracefully navigate the entire course. However, one race concluded with a loss of power, necessitating a tow truck—signifying compression loss in the engine. Reluctant to undergo another repair, I opted to purchase an engine from an M3 for 300,000 rubles, the inline “six” S52B32 (3.2 liters, 243 hp), along with Bilstein PSS coilover suspension. Despite these upgrades, my enjoyment was short-lived as this engine too required repairs after another thousand kilometers.

In essence, if I were a blogger, the E36 would be the quintessential project. It’s a content generator: capturing moments in auto shops, streaming from a tow truck, participating in Matsuri events, and delivering thrilling drift angles. However, in terms of track driving, it falls short. Even with the new suspension, driving the car lacks the excitement found in modern vehicles like the Toyota GT86.

We invested 2.5 million rubles into the car post-purchase, covering 20,000 kilometers over three years, only to sell the “three” for 800,000 rubles. Yet, the most significant loss was time—spending it on visits to service centers is justifiable only when it’s your profession. Moreover, purchasing aged vehicles for this purpose is wholly unnecessary.

Ilya Khlebushkin

Ilya Khlebushkin

Conducting an academic review of reliability for these cars seems peculiar, as the primary issue with 1990s BMWs stems from age, rendering the year of manufacture irrelevant beyond the ‘youngtimer’ concept. While one could discuss Nikasil, Alusil, or cylinder liners in M52 engines, or the varying reliability of ZF and GM automatic transmissions, uncovering a pristine ‘time capsule’ is as improbable as finding pirate treasure. Contrary to the optimistic odometer readings, many examples have surpassed 400,000 kilometers, with numerous undergoing overhauls or unit replacements. Hence, it’s worth noting that the best engines in the BMW E36 are the cast-iron petrol “sixes” 2.0 and 2.5 from the revered non-VANOS M50 series, while the BMW E39 and E38 boast the equally legendary diesel “sixes” of the M57 series.

Cooling system malfunctions, electrical issues, suspension problems, or steering failures are commonplace, yet, at this age, virtually any component can fail. Ultimately, it’s not the year of manufacture that’s crucial, but the condition—which often reflects a challenging last decade of service. Did you know, for instance, that an almost irreparable water-cooled generator costs nearly two average monthly salaries of a Russian?

Unfortunately, many BMWs were subjected to ruthless cost-cutting measures, including the installation of heaters from Zhigulis, power steering pumps from Nivas, or fuel pumps from Gazelles. In such conditions, they’re prone to sudden failures, which occur across the country.

While the likelihood of finding a well-preserved E38 “seven” is slightly higher than for the E36 due to later and lesser cost-saving measures, the greater complexity and initially modest population size pose challenges. Conversely, the abundance of E39 “fives” on the market is about sevenfold, owing to production in Kaliningrad. Moreover, until 2009, remarkably fresh E39s were imported from Japan—a market where left-hand drive “fives” were popular. Yet, due to the exorbitant customs duties (over 1 million rubles), importing BMWs from Japan is viable only as a source of spare parts.

Regarding nearby “Eurasian” territories, the situation is even bleaker. Cars from Armenia can now be registered in Russia only if they were initially imported before 2014, while those from Belarus must comply with Euro-5 standards or be older than 30 years—significantly limiting options. Moreover, these regions often imported vehicles from the lower end of the European market, rather than collectible specimens.

The key when navigating our secondary market lies in avoiding temptingly low prices. The disparity between top and bottom prices for each model is staggering! The third series ranges from 80,000 to 800,000 rubles, the “five” from 100,000 to a million, and the “seven” from 150,000 to one and a half million.

Corrosion poses a significant threat to all three models, with the E36 being particularly susceptible. Instead of focusing solely on fender holes, inquire about the strength of suspension mounts and the car’s ability to be lifted with a jack. The “five” and “seven” are not far behind, with sills, floors, and arches often exhibiting signs of corrosion. Thus, it’s advisable to seek out specimens with southern residence permits to minimize exposure to salt. Additionally, remain vigilant of any past criminal activities associated with prospective purchases.

However, there’s a silver lining: BMW E36, E39, and E38 models in genuinely good condition have ceased depreciating and hold promise for future appreciation—provided they survive.

Photo: Georgy Balabadzhyan | Dmitry Pitersky | BMW Company | Nikita Kolobanov | Sergei Udotov

This a translation. You can read an original article here: Ок, бумеры: «тройка», «пятерка» и «семерка» из девяностых

Published March 13, 2024 • 24m to read