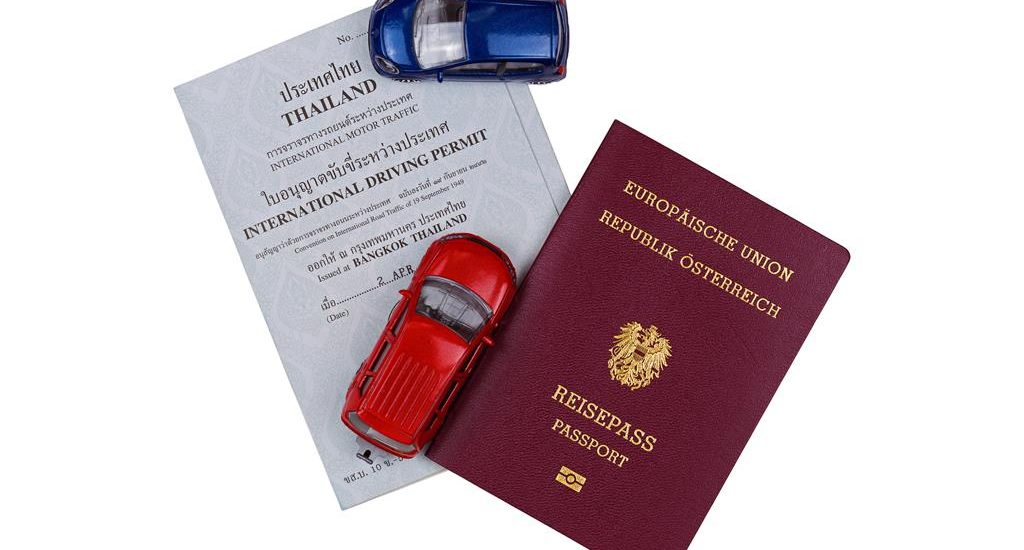

An International Driving Permit (IDP) is an official document that translates a motorist’s home country driver’s license into multiple languages, allowing them to drive in foreign countries that recognize it. Sometimes referred to as an “international driver’s license,” the IDP is not a standalone license – it must be carried alongside a valid domestic driving license to be valid. An IDP is printed as a small A6-size booklet (slightly larger than a passport) with a standardized format, typically a gray cover and multiple pages of translations in major languages (English, French, Spanish, Russian, etc.). Because it contains an official multilingual translation of the driver’s information and license classifications, an IDP helps local authorities interpret a foreign license and verify that the holder is qualified to drive. This document is regulated by United Nations road traffic conventions and is a legal requirement or recommended in many countries for visitors driving abroad. The sections below outline the latest international regulations governing IDPs, the countries that recognize them, and the process for obtaining one, with up-to-date information and official guidance.

Legal Framework and Regulations

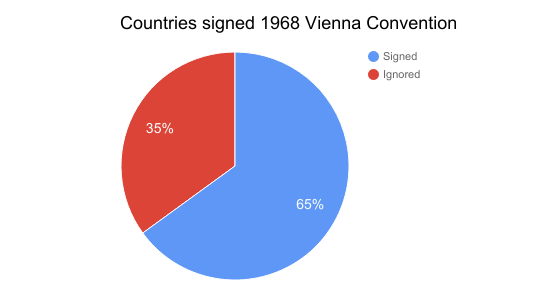

International Driving Permits are governed by international treaties that set uniform standards for driving documents. There are three historical conventions that established IDPs: the 1926 Paris Convention, the 1949 Geneva Convention on Road Traffic, and the 1968 Vienna Convention on Road Traffic. Today, the 1949 and 1968 conventions are the primary legal frameworks, with the 1968 Vienna Convention being the most recent and comprehensive. Countries that are parties to these conventions agree to recognize IDPs issued by other contracting states, subject to the conventions’ rules.

Under the 1949 Geneva Convention, an IDP is valid for one year from its date of issue. The permit is a paper booklet that mirrors the content of the holder’s national license (including name, photo, and vehicle categories) translated into standardized categories and multiple languages. The 1949 Convention’s IDP model must be honored by all 102 countries that are party to that convention (as of 2025). The document cannot be used for driving in the country where it was issued – it is intended only for international travel. In fact, the convention specifies that an IDP is not valid in its country of issuance and only the country in which a driver is licensed may issue that individual’s IDP.

The 1968 Vienna Convention introduced updated regulations for IDPs. It modernized the IDP format (with amendments in 2011 to standardize license categories and layout) and extended the possible validity period. According to the 1968 Convention, an IDP must have an expiration no more than three years from the issue date (or until the domestic license’s expiration, if sooner). However, regardless of its longer validity, when used abroad it is generally only valid for up to one year in a given foreign country. After one year of continuous residence, most countries require the driver to obtain a local license. As of the latest update, 83 countries have ratified the 1968 Convention, and for those countries the 1968 rules supersede the older 1949 rules. If a nation is party to both conventions, the newer convention’s provisions take precedence. Notably, some countries – for example, the United States, China, and others – have not ratified the 1968 Convention. Those countries typically recognize IDPs under the 1949 Convention instead, or through separate reciprocal arrangements.

Requirements for Valid Use: In all cases, the IDP is only valid when presented together with the original driving license from the driver’s home country. The IDP is essentially a translation and certification of the home license, so the two documents go hand-in-hand. If a driver cannot produce their actual domestic license, the IDP alone is not sufficient to legally drive. Additionally, an IDP does not confer any driving privileges beyond what the home license allows – it carries the same vehicle category endorsements as the home license. Drivers must still meet any minimum age or other requirements of the country they are visiting. (Under international rules, countries may refuse to recognize foreign licenses – even with an IDP – if the driver is under 18 years old, or under 21 for certain heavy vehicle categories. In practice, most issuing agencies will only issue an IDP to drivers aged 18 or above for this reason.) It’s also important to note that an IDP cannot be used to drive in the license holder’s own country – for example, a British driver’s UK-issued IDP is not valid for driving within the UK.

Most Recent Updates: The Vienna Convention of 1968 (with its 2011 amendments) represents the most up-to-date international legal standard for IDPs. This introduced the now-standardized booklet format and the longer validity period mentioned above. Many countries have updated their national laws to align with the 1968 Convention’s provisions. For instance, since the convention’s amendment came into force in March 2011, all contracting states issue IDPs in the new format defined in Annex 7 of the convention. In practical terms, this means the IDP you obtain today will likely be valid for up to three years (if your local license remains valid) and will contain standardized information that is recognized by all countries party to the convention. Always check the specific rules of the country you plan to visit, as some countries have additional requirements or variations (for example, some may require an IDP only after a certain period of driving on a visitor’s license, or may have their own national permit for long-term residents).

Global Recognition and Participating Countries

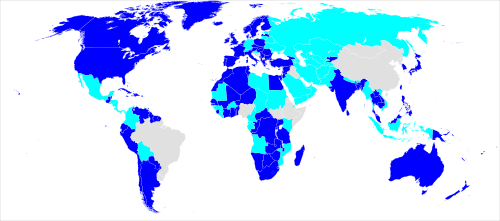

Global recognition of International Driving Permits: Countries shaded in blue recognize the IDP under the 1949 and/or 1968 UN Road Traffic Conventions (grey indicates countries or regions that do not). International Driving Permits are widely recognized around the world. In fact, the vast majority of countries accept an IDP as the proper document for foreign visitors to drive legally, in addition to carrying their home license. IDPs are a product of United Nations treaties, and any country that is a party to the 1949 or 1968 convention will honor a properly issued IDP from another member country. As of 2025, over 100 countries are parties to the 1949 Geneva Convention and over 80 countries are parties to the 1968 Vienna Convention on Road Traffic. This includes most of Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa – covering nearly all popular travel destinations. In total, an IDP is recognized as a valid form of identification for driving in over 140 countries worldwide. Automobile associations often cite an even higher number – for example, the American Automobile Association notes that an IDP is useful in 150 countries worldwide as an officially recognized identification document for drivers. In many of these countries, driving without an IDP (if your license is foreign) could be a violation resulting in fines or difficulties with authorities, especially if the local police cannot read the language on your home license.

It’s important to understand that some countries require an IDP by law for foreign drivers, while others highly recommend it as a best practice. “Required” means that if you drive without an IDP (and local license) in those countries, you are technically driving illegally. “Recommended” means that while it might not be strictly mandatory under law, having one will greatly smooth interactions with rental agencies and traffic officials. For example, Japan, India, Brazil, Australia, and Turkey are among the countries that explicitly require an IDP for most visitors driving with a foreign license. Countries like Mexico and Canada officially recognize an IDP (and some sources recommend carrying one), even though in practice short-term visitors from certain countries (e.g. the U.S.) may be allowed to drive with just their home license for a limited time. Because regulations can vary, it is wise to check the specific requirements of each country on your itinerary. Government travel sites or that country’s embassy can provide guidance on whether an IDP is needed.

There are also cases where an IDP is not needed due to multi-national agreements. Notably, within the European Union and European Economic Area (EEA), a valid driving license from one member state can be used in another member state without an IDP. For instance, a French citizen can drive in Germany or Italy on their French license alone, thanks to EU law recognizing mutual driving privileges. Similarly, certain other regional agreements (for example, among member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council or within ASEAN in Southeast Asia) allow visitors from neighboring countries to drive without an IDP. In addition, some countries have bilateral agreements that honor each other’s licenses. Always verify if such an arrangement exists for your destination; otherwise, obtaining an IDP is the safest course.

Finally, a few countries are not parties to either the 1949 or 1968 conventions and may not recognize IDPs at all. The largest example is Mainland China, which does not recognize international driving permits and generally does not allow foreign licenses to be used; visitors in China must obtain a local temporary driving permit or license. Vietnam is another country where an IDP might not be valid unless it has been exchanged for a local permit (though rules have been evolving). Ethiopia and Somalia are examples of countries that were under the older 1926 Convention rules; Somalia, in particular, requires a 1926 Convention IDP (a special case, since most countries no longer use that older format). These exceptions are relatively few, but they underscore the importance of checking country-specific driving rules. If you plan to drive in a country that is greyed out on the map (non-participating), contact that country’s embassy or consult official travel advisories for instructions – you may need to obtain a local permit or meet other requirements to drive there legally.

The Vienna Convention was adopted by 84 states:

| Participant | Signature | Accession(a), Succession(d), Ratification |

| Albania | 29 Jun 2000 a | |

| Andorra | 25 Sep 2024 a | |

| Armenia | 8 Feb 2005 a | |

| Austria | 8 Nov 1968 | 11 Aug 1981 |

| Azerbaijan | 3 Jul 2002 a | |

| Bahamas | 14 May 1991 a | |

| Bahrain | 4 May 1973 a | |

| Belarus | 8 Nov 1968 | 18 Jun 1974 |

| Belgium | 8 Nov 1968 | 16 Nov 1988 |

| Benin | 7 Jul 2022 a | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1 Sep 1993 d | |

| Brazil | 8 Nov 1968 | 29 Oct 1980 |

| Bulgaria | 8 Nov 1968 | 28 Dec 1978 |

| Cabo Verde | 12 Jun 2018 a | |

| Central African Republic | 3 Feb 1988 a | |

| Chile | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| Costa Rica | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 24 Jul 1985 a | |

| Croatia | 23 Nov 1992 d | |

| Cuba | 30 Sep 1977 a | |

| Czech Republic | 2 Jun 1993 d | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 25 Jul 1977 a | |

| Denmark | 8 Nov 1968 | 3 Nov 1986 |

| Ecuador | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| Egypt | 15 Dec 2023 a | |

| El Salvador | 27 Aug 2024 a | |

| Estonia | 24 Aug 1992 a | |

| Ethiopia | 25 Aug 2021 a | |

| Finland | 16 Dec 1969 | 1 Apr 1985 |

| France | 8 Nov 1968 | 9 Dec 1971 |

| Georgia | 23 Jul 1993 a | |

| Germany | 8 Nov 1968 | 3 Aug 1978 |

| Ghana | 22 Aug 1969 | |

| Greece | 18 Dec 1986 a | |

| Guyana | 31 Jan 1973 a | |

| Holy See | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| Honduras | 3 Feb 2020 a | |

| Hungary | 8 Nov 1968 | 16 Mar 1976 |

| Indonesia | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| Iran | 8 Nov 1968 | 21 May 1976 |

| Iraq | 1 Feb 2017 a | |

| Israel | 8 Nov 1968 | 11 May 1971 |

| Italy | 8 Nov 1968 | 2 Oct 1996 |

| Kazakhstan | 4 Apr 1994 a | |

| Kenya | 9 Sep 2009 a | |

| Kuwait | 14 Mar 1980 a | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 30 Aug 2006 a | |

| Latvia | 19 Oct 1992 a | |

| Liberia | 16 Sep 2005 a | |

| Liechtenstein | 2 Mar 2020 a | |

| Lithuania | 20 Nov 1991 a | |

| Luxembourg | 8 Nov 1968 | 25 Nov 1975 |

| Maldives | 9 Jan 2023 a | |

| Mexico | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| Monaco | 6 Jun 1978 a | |

| Mongolia | 19 Dec 1997 a | |

| Montenegro | 23 Oct 2006 d | |

| Morocco | 29 Dec 1982 a | |

| Myanmar | 26 Jun 2019 a | |

| Netherlands | 8 Nov 2007 a | |

| Niger | 11 Jul 1975 a | |

| Nigeria | 18 Oct 2018 a | |

| North Macedonia | 18 Aug 1993 d | |

| Norway | 23 Dec 1969 | 1 Apr 1985 |

| Oman | 9 Jun 2020 a | |

| Pakistan | 19 Mar 1986 a | |

| Peru | 6 Oct 2006 a | |

| Philippines | 8 Nov 1968 | 27 Dec 1973 |

| Poland | 8 Nov 1968 | 23 Aug 1984 |

| Portugal | 8 Nov 1968 | 30 Sep 2010 |

| Qatar | 6 Mar 2013 a | |

| Republic of Korea | 29 Dec 1969 | |

| Republic of Moldova | 26 May 1993 a | |

| Romania | 8 Nov 1968 | 9 Dec 1980 |

| Russian Federation | 8 Nov 1968 | 7 Jun 1974 |

| San Marino | 8 Nov 1968 | 20 Jul 1970 |

| Saudi Arabia | 12 May 2016 a | |

| Senegal | 16 Aug 1972 a | |

| Serbia | 12 Mar 2001 d | |

| Seychelles | 11 Apr 1977 a | |

| Slovakia | 1 Feb 1993 d | |

| Sloveniа | 6 Jul 1992 d | |

| South Africa | 1 Nov 1977 a | |

| Spain | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| State of Palestine | 11 Nov 2019 a | |

| Sweden | 8 Nov 1968 | 25 Jul 1985 |

| Switzerland | 8 Nov 1968 | 11 Dec 1991 |

| Tajikistan | 9 Mar 1994 a | |

| Thailand | 8 Nov 1968 | 1 May 2020 |

| Tunisia | 5 Jan 2004 a | |

| Türkiye | 22 Jan 2013 a | |

| Turkmenistan | 14 Jun 1993 a | |

| Uganda | 23 Aug 2022 a | |

| Ukraine | 8 Nov 1968 | 12 Jul 1974 |

| United Arab Emirates | 10 Jan 2007 a | |

| United Kingdom | 8 Nov 1968 | 28 Mar 2018 |

| Uruguay | 8 Apr 1981 a | |

| Uzbekistan | 17 Jan 1995 a | |

| Venezuela | 8 Nov 1968 | |

| Viet Nam | 20 Aug 2014 a | |

| Zimbabwe | 31 Jul 1981 a |

It should be noted that you should have no problems driving a car in these countries, unlike countries not included in the list. In practice, most offices of car rental companies require an International Driver’s License, even if the driver shows a printed copy of the Vienna Convention to the rental manager.

There is a list of countries where the IDP is mandatory (the states in which the Geneva Convention was adopted):

| Participant | Signature | Accession(a), Succession(d), Ratification |

| Albania | 1 Oct 1969 a | |

| Algeria | 16 May 1963 a | |

| Argentina | 25 Nov 1960 a | |

| Australia | 7 Dec 1954 a | |

| Austria | 19 Sep 1949 | 2 Nov 1955 |

| Bahrain | 11 Mar 2025 a | |

| Bangladesh | 6 Dec 1978 a | |

| Barbados | 5 Mar 1971 d | |

| Belgium | 19 Sep 1949 | 23 Apr 1954 |

| Benin | 5 Dec 1961 d | |

| Botswana | 3 Jan 1967 a | |

| Brunei Darussalam | 12 Mar 2020 a | |

| Bulgaria | 13 Feb 1963 a | |

| Burkina Faso | 31 Aug 2009 a | |

| Cambodia | 14 Mar 1956 a | |

| Canada | 23 Dec 1965 a | |

| Central African Republic | 4 Sep 1962 d | |

| Chile | 10 Aug 1960 a | |

| Congo | 15 May 1962 a | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 8 Dec 1961 d | |

| Croatia | 7 Feb 2020 a | |

| Cuba | 1 Oct 1952 a | |

| Cyprus | 6 Jul 1962 d | |

| Czech Republic | 2 Jun 1993 d | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 6 Mar 1961 d | |

| Denmark | 19 Sep 1949 | 3 Feb 1956 |

| Dominican Republic | 19 Sep 1949 | 15 Aug 1957 |

| Ecuador | 26 Sep 1962 a | |

| Egypt | 19 Sep 1949 | 28 May 1957 |

| Estonia | 1 Apr 2021 a | |

| Fiji | 31 Oct 1972 d | |

| Finland | 24 Sep 1958 a | |

| France | 19 Sep 1949 | 15 Sep 1950 |

| Georgia | 23 Jul 1993 a | |

| Ghana | 6 Jan 1959 a | |

| Greece | 1 Jul 1952 a | |

| Guatemala | 10 Jan 1962 a | |

| Haiti | 12 Feb 1958 a | |

| Holy See | 5 Oct 1953 a | |

| Hungary | 30 Jul 1962 a | |

| Iceland | 22 Jul 1983 a | |

| India | 19 Sep 1949 | 9 Mar 1962 |

| Ireland | 31 May 1962 a | |

| Israel | 19 Sep 1949 | 6 Jan 1955 |

| Italy | 19 Sep 1949 | 15 Dec 1952 |

| Jamaica | 9 Aug 1963 d | |

| Japan | 7 Aug 1964 a | |

| Jordan | 14 Jan 1960 a | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 22 Mar 1994 a | |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 6 Mar 1959 a | |

| Lebanon | 19 Sep 1949 | 2 Aug 1963 |

| Lesotho | 27 Sep 1973 a | |

| Liechtenstein | 2 Mar 2020 a | |

| Lithuania | 4 Feb 2019 a | |

| Luxembourg | 19 Sep 1949 | 17 Oct 1952 |

| Madagascar | 27 Jun 1962 d | |

| Malawi | 17 Feb 1965 d | |

| Malaysia | 10 Sep 1958 a | |

| Mali | 19 Nov 1962 d | |

| Malta | 3 Jan 1966 d | |

| Monaco | 3 Aug 1951 a | |

| Montenegro | 23 Oct 2006 d | |

| Morocco | 7 Nov 1956 d | |

| Namibia | 13 Oct 1993 d | |

| Netherlands | 19 Sep 1949 | 19 Sep 1952 |

| New Zealand | 12 Feb 1958 a | |

| Niger | 25 Aug 1961 d | |

| Nigeria | 3 Feb 2011 a | |

| Norway | 19 Sep 1949 | 11 Apr 1957 |

| Papua New Guinea | 12 Feb 1981 a | |

| Paraguay | 18 Oct 1965 a | |

| Peru | 9 Jul 1957 a | |

| Philippines | 19 Sep 1949 | 15 Sep 1952 |

| Poland | 29 Oct 1958 a | |

| Portugal | 28 Dec 1955 a | |

| Republic of Korea | 14 Jun 1971 d | |

| Romania | 26 Jan 1961 a | |

| Russian Federation | 17 Aug 1959 a | |

| Rwanda | 5 Aug 1964 d | |

| San Marino | 19 Mar 1962 a | |

| Senegal | 13 Jul 1962 d | |

| Serbia | 12 Mar 2001 d | |

| Sierra Leone | 13 Mar 1962 d | |

| Singapore | 29 Nov 1972 d | |

| Slovakia | 1 Feb 1993 d | |

| Slovenia | 13 Jul 2017 d | |

| South Africa | 19 Sep 1949 | 9 Jul 1952 a |

| Spain | 13 Feb 1958 a | |

| Sri Lanka | 26 Jul 1957 a | |

| Sweden | 19 Sep 1949 | 25 Feb 1952 |

| Switzerland | 19 Sep 1949 | |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 11 Dec 1953 a | |

| Thailand | 15 Aug 1962 a | |

| Togo | 27 Feb 1962 d | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 8 Jul 1964 a | |

| Tunisia | 8 Nov 1957 a | |

| Türkiye | 17 Jan 1956 a | |

| Uganda | 15 Apr 1965 a | |

| United Arab Emirates | 10 Jan 2007 a | |

| United Kingdom | 19 Sep 1949 | 8 Jul 1957 |

| United States of America | 19 Sep 1949 | 30 Aug 1950 |

| Venezuela | 11 May 1962 a | |

| Viet Nam | 2 Nov 1953 a | |

| Zimbabwe | 1 Dec 1998 d |

This means that an international drive’r document is needed in addition to the national driver’s license. In its essence, it is a translation of the national driver’s license into the main languages of the world:

- English;

- Russian;

- Spanish;

- French.

However, the list of languages could be longer, which is better.

The IDL is not a stand alone document

Drivers should take into account that the IDL is recognized as valid only if a national driver’s license is also present. An international license has listed the number of the domestic one. When traveling abroad, you must have both licenses.

The new International Driver’s License (starting in 2011) is a book of A6 format, filled by hand or by using a printing device. Records of documents are entered only in Latin letters and Arabic numerals. The front side of the document indicates the date of issue and the period of validity of the license, the name of the body that issued the document, and country in which the document was issued. In addition, the series and numbers of the national driver’s license is written or printed on the front page. If the driver has restrictions, then these are put on the second sheet. The third sheet indicates the driver’s data: first and last name, date of birth, place of birth, and place of residence or registration.

All categories necessary for driving must be marked with an oval seal; other categories are crossed out.

What if you don’t have an IDL?

There are consequences for not having an IDL for the driver:

1. If there is no driver’s license of an international standard, the driver may be denied the right to cross the border.

2. When renting a car abroad, staff may refuse to serve you.

3. If you drive abroad in Europe without an IDL and authorities of the country receive confirmed information of this, you can be fined up to 400 euros. If there is a significant violation of the rules, it is likely the driver could go to jail.

4. In the case of an accident, insurance companies may refuse to recognize the driver as the insured if they do not have an IDL.

In any case, first you should carefully study the local traffic rules. In many cases, foreign drivers have been fined abroad just because they did not know the local requirements and driving rules of the country in which they were driving.

Summary

Automobile tourism is developing rapidly. International Driver’s Licenses are in demand today in many countries in the world. When traveling abroad, it is necessary to have a document that is relevant to the national driver’s license and understandable in the conditions of the specific country.

Plus having an IDL makes it easy to rent a car, as the insurance will become more affordable.

Published January 10, 2017 • 15m to read