We typically steer clear of exhibits in such a state of disrepair in our “Kunstkamera.” But in this case, there’s nothing we can do; there were only around 36 of these limousines, like this one, built almost six decades ago, and even fewer have survived to the present day.

For many years, the Chrysler Corporation considered it essential to have at least one high-class multi-passenger vehicle in its product line. The prestigious model called the Imperial had crowned the corporate lineup since 1926; initially, this term only referred to a specific type of body, but it quickly transformed into the name of a distinct series of Chrysler cars – a luxury series.

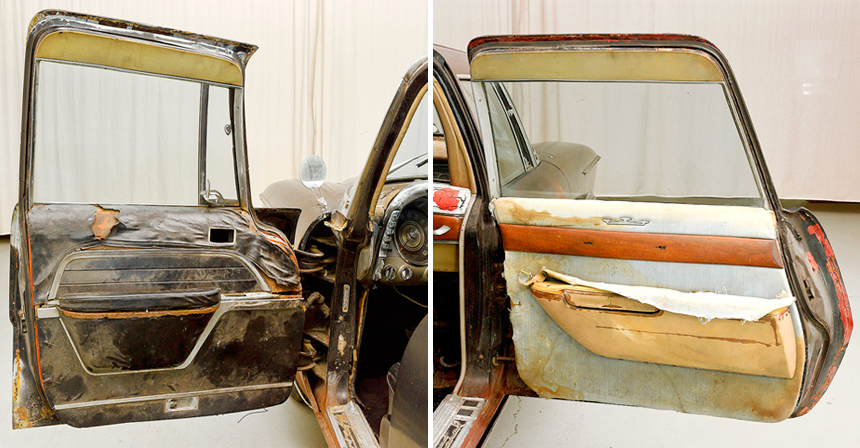

The remnants of former luxury. It’s mind-boggling how such an expensive and rare vehicle ended up in such a dismal state. Judging by the odometer, it has driven just over fifty thousand miles. Achieving complete authenticity during restoration is unlikely, as the upholstery fabric that was available in 1957 is a rare find today. Finding a close match is the only option. The leather for the front section of the cabin, however, will likely be easier to match, and it has held up better than the fabric.

Until the mid-1950s, there was always a long-wheelbase limousine in the Imperial lineup, and they were manufactured directly at the company’s factory, although the Chrysler Corporation didn’t shy away from using the services of external coachbuilders. However, in 1956, it was time to reconsider the matter. Imperial had just been made into a separate brand (up until 1955, it was always sold as the Chrysler Imperial), and demand for limousines in the country had steadily declined since the post-war years. Competitors were one by one leaving the segment, leaving it to the mercy of the victor, the General Motors Corporation, which steadfastly kept producing its Cadillac Fleetwood 75 model. Lincoln had already retreated after 1945, making limousines, if at all, only on special orders from the White House. Packard held on for a while longer, relying on help from their long-time partners at the Henney coachbuilding company. But with the transition to the 1955 models, it withdrew as well, leading to the immediate demise of the Henney firm, left without orders.

Winning the competition in this special market segment was an uphill battle. Yet the Chrysler Corporation didn’t give in without a fight, courageously producing 198 vehicles, entirely on their own, between 1955 and 1956 with an extended wheelbase of 3797 mm. However, 85 of these vehicles couldn’t be considered limousines, as they didn’t have an internal partition in the cabin. By 1957, the corporation was planning a “quantum leap” with a complete replacement of all the models being produced at that time with more modern designs. A separate factory department for multi-passenger but low-volume vehicles didn’t fit into this new picture. It had to be excluded.

A solution was found, not just anywhere but overseas, in the Old World. From the early 1950s, practically all of Chrysler’s promising prototypes were sent to be realized by the Italian coachbuilding atelier, Carrozzeria Ghia. Over the years, the relationship between Virgil Exner, the head of the corporate styling division, and Luigi Segre, one of the two owners of the Ghia coachbuilding company, had become very warm and friendly. So, it’s not surprising that the idea of engaging Italian partners in the production of limousines for the American corporation was met with enthusiasm from both sides. The challenge then was to deal with logistics; after all, one thing is prototyping, and another is a series, even if it’s a small one.

In practice, the process of producing American limousines in Italy looked something like this. Italian craftsmen received a car kit shipped from the United States, by sea, not air. This kit consisted of a production two-door body of an Imperial car, mounted on the frame of an open model from the same brand, a convertible. The convertible frame had an additional X-shaped crosspiece, making it more rigid. The engine, transmission, and all other components of the chassis were already assembled on the frame. Instead of the two standard-length doors, a full set of doors from a four-door Imperial sedan was installed in the cabin. Additional external finish elements, front and rear bumpers, curved side windows, various internal fittings, and other necessary items were added, including extended fuel lines, brake lines, exhaust manifolds, and driveshafts – everything that the coachbuilders needed to install on-site during the final vehicle assembly. Every detail had to be considered to avoid the hassle of shipping a suddenly needed part back and forth across the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea. In the trunk, insulating and finishing materials in rolls, as well as cans of paint in the color specified for each particular vehicle, were usually stored. All these items were then shipped by rail to the seaport and further transported to Italy by sea. In the port of Genoa, the recipients collected the car kit and delivered it to their workshop by road.

Upon arrival at Ghia, the first step was to cut both the body and frame in half, extending each by about half a meter. The roof, however, was removed from the body and worked on separately. The choice of the two-door body from the car kit was due to the specific configuration of the rear part of the roof. During the extension of the wheelbase of the chassis, extra reinforcements were added at necessary points. Afterward, all the aforementioned conduits and driveshafts were mounted in place on it.

Italian craftsmen then worked on the doors. The upper part of the doors had to be modified to slightly overlap the roof, and the external finishing was replaced at the rear, eliminating the cutouts on the rear edge since, after extending the base, they were no longer supposed to encircle the wheel arch cutouts. At this stage, the central body pillar was also mounted in place; it had to be fabricated first because the original body didn’t have this pillar at all. Simultaneously, they extended and formed the roof panel, later adjusted to fit the shape and positioning of the upper part of the doors. After assembling and fitting everything together, the craftsmen installed the ventilation ducts of the air conditioning system (the Airtemp system came from the factory as part of the car kit, but its standard ducts weren’t suitable for the extended limousine and needed extensions). Only after this did they add the headliner to the interior. It used a fabric originally intended for expensive men’s suits and had to be steamed before it would conform to its place properly.

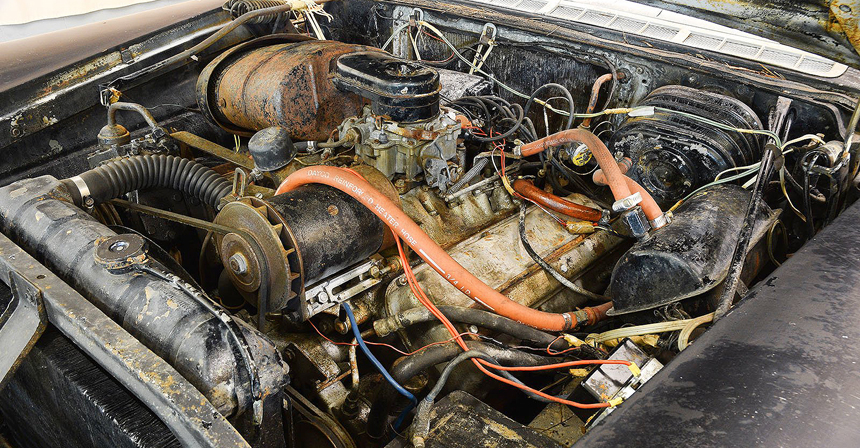

The trunk floor clearly required replacement, but the residing air conditioner seems to have survived.

Once the body was assembled, it was ready for painting. In Ghia’s body workshop, this was a time-consuming and labor-intensive procedure, sometimes taking more than two weeks. The body arrived as part of the car kit, already primed. However, the remade parts were first sanded, and their surfaces were leveled (the technology used involved heating these surfaces with a special lead-based solder, with up to 60 kg of solder used on a single car). Then, the primer was applied. Just before painting, the doors were finally hung, all joints and gaps on the body were aligned to a width of four millimeters (which sometimes required 17 man-hours of work); afterward, the surface was cleaned of any potential contaminants with a special solution and covered with a layer of pale green “stucco” – the signature compound of the Italian masters, serving as the basis for the initial paint layer. This layer was applied immediately after drying the green chromo-zinc matte primer, which allowed any surface defects to be fully revealed. These imperfections were then puttied and sanded, and only then could the actual painting begin.

Only four colors were offered for the limousine – black, dark blue, dark green, and dark red. These were applied in multiple layers, with each layer being sanded after drying, ensuring thickness and uniformity. To finish, a dried body was hand-rubbed with a special “polish” containing an exotic substance known as “sepia” – the same “ink” that octopuses use to protect themselves from predators. Jeffrey Godshall, an automotive historian and former Chrysler stylist, claims that the “sepia” was extracted from certain purely Mediterranean species of cephalopods. This process gave the body surface a unique mirror-like shine. After achieving this finish, all the shiny decorative details, both those that came with the car kit from across the ocean and those specially manufactured on-site, were attached – moldings, window frames, emblems, nameplates, and so on. Finally, as a “final touch,” a cream-colored pinstripe was applied along the sides of the body by hand with a fine brush, running from the front to the rear.

The engine will certainly need an overhaul. It’s likely not worn out but has simply been sitting idle, requiring meticulous attention. The automatic transmission, and indeed the entire suspension, will also need a thorough inspection and refurbishment.

Next came the turn of the interior. The seats arrived from the United States without upholstery. The front seats, as customary in limousines, were covered in genuine leather, while the rear seats used noble fabrics, mostly of gray or beige hues, mainly of Italian origin. The internal door trim was also made of leather for the front section and a corresponding fabric for the rear. An internal partition with a drop-down window was installed in place, wiring was run to the electric window mechanisms, additional foldable seats were mounted, and a carpet covering was placed on the floor (nylon in the front and trunk, wool in the rear). In total, five interior finishing options were offered, which, combined with four body colors, resulted in 32 different combinations of the vehicle’s interior and exterior solutions.

The faux radiator grille design from the 1957 model year is combined with the headlight design from the 1958 model year. Limousines Imperial began appearing on the market much later than all other body variants, and by that time, the issue of using paired front headlights had been successfully resolved across all states.

A fully completed limousine underwent a test drive on Italian streets to ensure it didn’t squeak or rattle during motion. If any shortcomings were identified, they were addressed before shipping. The car was once again wrapped entirely in soft fabric and packed into a wooden transport container, meticulously crafted just like the car’s bodywork at Carrozzeria Ghia. In a documented case, a custom-made limousine for an Arabian sheikh was transported by train through the Arabian desert. Bandits attacked the train, took the car out of its container, and left the luxurious vehicle behind. No surprise there, as what use is such a car in the desert where camels reign supreme?

Before reaching the port of Genoa, the packaged cars traveled on auto trains through narrow and winding Italian roads of varying quality. A modern highway was constructed by Fiat for its import-export needs, but it was open to the public only on weekends, requiring a fee for use during the week. This intricate transportation process took a significant amount of time, so from placing an order to receiving the finished car, it could take up to half a year.

Chrome also needs to be updated. In short, it’s a lot of hassle… but it’s worth it!

Working on each Crown Imperial limousine took about a month. Those considering restoring a vehicle like the one shown here must realize what they are getting into. The body will need to be stripped down to the metal and then completely repainted. Of course, it’s not 1957 anymore, and nobody will use cephalopods for their magical “sepia.” New paint materials have emerged over the years. However, restoring the paint will still take a considerable amount of time. The interior will need to be completely replaced as it’s not suitable in its current condition. Plus, you’ll need to source suitable materials; otherwise, the restoration won’t be considered authentic. Surprisingly, this car is still in running condition, but both the engine and the transmission will need overhauling to bring them to perfect working order. The electrical system will also require thorough attention, and it would be wise to obtain a wiring diagram in advance because it’s a complex system that can’t be easily figured out. Significant problems will undoubtedly arise with the rubber door seals. The old ones will likely crumble to dust; the car is already sixty years old, and it’s simply hard to find new ones as they are non-standard. Certain elements of the external decor and some of the hardware are missing – it seems that someone in the past made attempts to restore it but quickly gave up due to the enormity of the task. Fortunately, nothing is lost; the car is quite complete.

This vehicle, though battered, is not beyond hope. With dedicated work and a love for the craft, it can be restored to its original splendor.

Restorers, this is your call to bravery. The Crown Imperial Limousine awaits its revival.

Photo: Sean Dugan, Hyman Ltd.

This a translation. You can read an original article here: Комплектный, под реставрацию. Crown Imperial Limousine by Carrozzeria Ghia в рассказе Андрея Хрисанфова

Published January 03, 2024 • 10m to read