In 1946, as the world emerged from the shadows of World War II, the renowned British company Rolls-Royce embarked on the production of civilian vehicles once again. Among their offerings was a direct post-war descendant of their pre-war model – the Wraith. The immense 12-cylinder Phantom III was deemed too extravagant for the challenging post-war era, both in terms of production and practical use. On the other hand, the Wraith, which means “Spirit,” was a direct descendant of the 20/25 model. This car was conceived and designed as a “driver-owner’s car,” relatively compact and easier to handle compared to the colossal Phantoms, which required a physically robust and well-trained professional to manage.

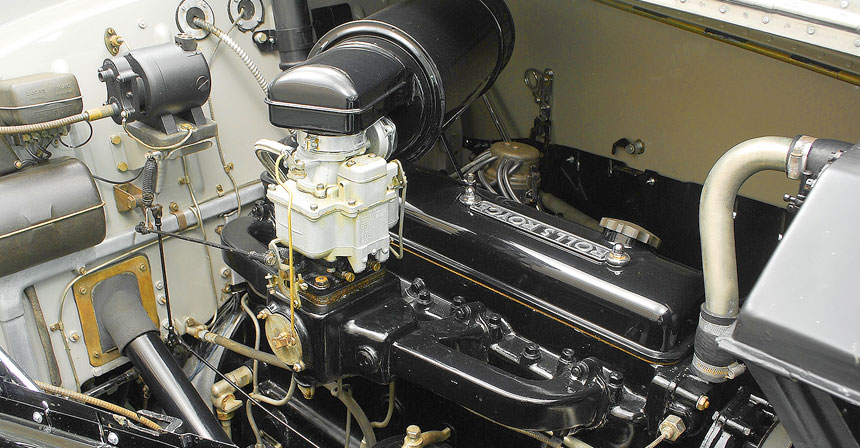

Of course, the post-war Rolls-Royce was not a mere replica of its pre-war counterpart. The chassis featured a new frame and a revised design of an independent front suspension with coil springs. The improved inline-six engine, with its characteristic F-head configuration, purportedly generated a robust 125 horsepower – a figure the manufacturer traditionally held close to its chest. Several other minor refinements were introduced to distinguish the new Rolls-Royce from its predecessor. And to underscore this transformation, they added “Silver” to its name. What was once the “Wraith” became the “Silver Wraith,” a step up the ladder of opulence.

As was customary for Rolls-Royce, they offered the Silver Wraith primarily as a chassis, without a body. Affluent buyers were expected to commission a coachbuilder to craft a body tailored to their individual tastes and preferences. Most of these custom body orders were handled by local British coachbuilders, the ones that had survived the challenging wartime years. However, in our story, the elegant two-door body on this Rolls-Royce was crafted by the renowned French atelier Franay. This unique creation was the result of a commission by a discerning Swiss doctor, Dr. M. Adel Latif, a man of refined taste and considerable means.

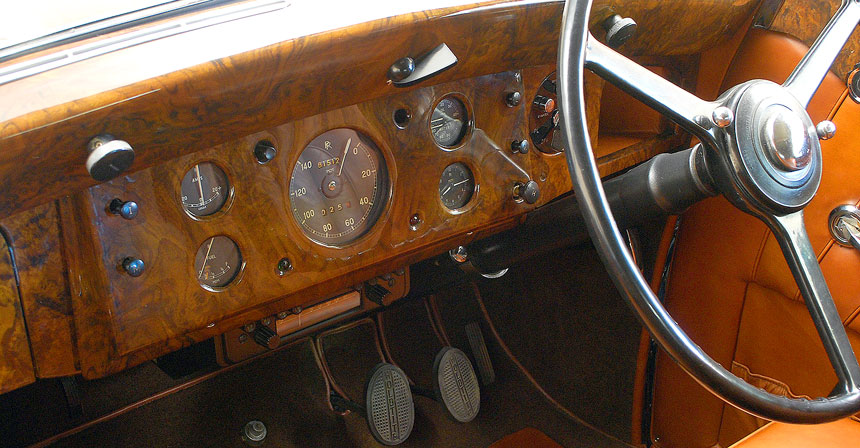

View of the driver’s workplace. The glove compartment on his side has no cover.

The upholstery of all seats is leather. The driver’s seat cushion is slightly “trimmed” to facilitate gear shifting; the lever for the four-speed transmission is located by the driver’s right hand.

Until 1951, the Silver Wraith was available in only one wheelbase length – 3,226 millimeters. The “long chassis” version (3,373 millimeters) was introduced after Rolls-Royce had plans for a “senior” model to replace the aging Phantoms. In the interim, they designated the modified Bentley Mk. VI as the new “junior” model, fitted with a standardized closed four-door body. This transition to the “Silver Dawn” model marked the end of an era when all Rolls-Royces, whether stately sedans or sporty convertibles, were built on the same chassis, and the coachbuilder put the finishing touches according to the buyer’s taste.

The dashboard is made of natural wood of precious varieties. The instrument gauges are symmetrically grouped in the center, with the oil level and water temperature indicators in the cooling system displayed on a single dial (top right).

The Carrosserie Franay was established in Levallois-Perret, a suburb of Paris, by the master craftsman Jean-Baptiste Franay in 1903, just as the automotive era was dawning. Within a mere decade, the firm rose to prominence in the French coachbuilding industry. Unfortunately, World War I disrupted operations, and, like many others, they had to start anew after the war. Thankfully, by then, Jean-Baptiste’s son, Marius, had come of age and was able to lead the family business from 1922, taking it back to its former glory. During the interwar period of prosperity, the firm worked with vehicles from the world’s finest marques, both from the Old and New World, including Hispano-Suiza, Packard, Duesenberg, and Delage. Therefore, it’s not surprising that Rolls-Royce (and Bentley) buyers, as long as they weren’t bound by old British traditions, were happy to engage their services.

In this photo, the gleaming chrome details on the foldable front seats and the soft-top roof that lowers are especially evident. In the back, it might feel slightly snug. The rear bench features a fold-down central armrest. The rear bench features a fold-down central armrest.

The business proved to be astonishingly resilient. It weathered World War II as well as it had World War I. However, its customer base in the late forties was dwindling at an alarming rate, like old parchment. The mass shift of car manufacturers worldwide to integral body structures left traditional coachbuilders with a substantial decline in business, exacerbated by the post-war French government’s penchant for tormenting its high-end car producers. They had to accept orders for imported chassis, as was the case with this specific example.

The interior door upholstery is striking and elaborate, crafted from the same leather as the seats.

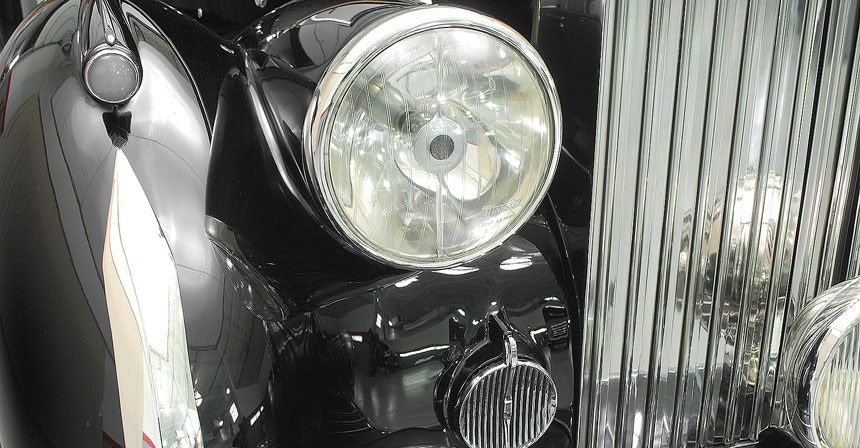

In the late forties, the pervasive trend of gaudy chrome adornments covering the entire body had yet to sweep across France, although later, Marius Franay was certainly seduced by it. On the doctor’s car, the saber-like trimmings, running along the edges of the front and rear fenders, were functionally justified: they protected the vehicle at all four corners from minor dings and scratches. Apart from these distinctive details, the gleaming bodywork was kept to a minimum: bumpers, the signature Rolls-Royce radiator (where would we be without it?), a thin strip along the waistline, and, perhaps, that’s it. Well, also the rings around the headlights and the windshield. Modest and stylish.

The frontal design is executed in the distinctly French manner: British coachbuilders had not yet ventured to move away from separate, free-standing headlights and install front lighting fixtures seamlessly into the fenders. The shining chrome “scimitars” covering the front edges of the fenders were also used by other French ateliers, notably Figoni & Falaschi.

The under-hood space is clean and spacious. The inline-six-cylinder engine has a displacement of 4,257 cubic centimeters; as for the power it generates, the company traditionally maintained proud silence.

If the artisans at Franay truly let their creativity shine in one aspect of their work, it was in the interior. The stylish leather upholstery, the veneer made from precious wood (on the doors and the dashboard), the exquisite fittings – all of this was executed with a truly French lightness that neither the English nor the Germans (including Erdmann & Rossi), nor even the Italians could match. Dr. Latif could be thoroughly satisfied with his British automobile infused with French flair.

By the mid-1950s, French automakers attempting to produce high-end, luxury vehicles faced the inevitable reality of ceasing their operations. Government policies, with a strictly dirigiste approach to the national car manufacturing industry, made the production of cars with an engine displacement exceeding two liters not only unprofitable but downright unsustainable. One by one, manufacturers who had weathered both the Great Depression and the war, producing fast and comfortable cars, such as Delage, Hotchkiss, Delahaye, and Talbot-Lago, exited the stage. This left the country’s coachbuilders reliant on sporadic orders using imported chassis. Carrosserie Franay, for instance, produced a batch of five cars in 1955 based on the chassis of a Bentley Continental. Later, they received a somewhat ironic “consolation prize” – a government order to create a ceremonial limousine for the country’s president using the chassis of the then-current Citroen 15CV. This project became the final masterpiece from the artists of Levallois-Perret.

Viewed from behind, the car exudes a sleek and fast appearance. The few shining details add a sense of elegance to its overall design.

Photo: Sean Dagen, Hyman Ltd.

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: «Серебряный дух» во французском духе: Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith by Franay 1947 года для швейцарского врача

Published December 21, 2023 • 6m to read