Wolves in sheep’s clothing? Certainly not. Even in their base models, the BMW E34 and the ‘124’ series Mercedes-Benz don’t pretend to be anything but what they are: predators. They exude a Wall Street wolf vibe, dressed in elegant Italian suits. Yet, in their M5 and 500 E guises, they truly transform into monsters once they leave the corporate parking lot.

As the last drizzles of a November thaw patter on the windshield, I only need to hold onto autumn for a mere six more seconds. Ahead lies the straightaway of the Dmitrovsky testing ground, with the rear tires of my BMW gripping the last dry patches of asphalt. “Finally, we meet, M5,” I think, “and I need all your dark magic now.”

Often, I’ve heard that the later E39 M5 “just isn’t the same,” that the genuine, untamed spirit of the M5 remained back in the early ’90s with the E34 version, which never wore collars. Yet, my own experience with a pristine E34, even a standard version, has eluded me. Instead, a colleague managed to pit a BMW 535i against a Mercedes-Benz 300 E three years ago. Since then, I’ve been obsessed with arranging the ultimate showdown, since the M5 of that era never participated in Auto Review tests, nor did we encounter its archrival, the Mercedes-Benz 500 E.

Now, both cars slowly approach the barrier of the testing ground, their halogen headlights from the golden age of automobile manufacturing lighting up the parking lot. This article may appear under the “retro test” category, but don’t be fooled. The BMW’s digital display reads just 26,900 km, while the Mercedes’ odometer shows 88,550. Do such beasts really age?

In reality, only the BMW’s mileage is verifiable; the Mercedes has likely traversed at least three times that distance. The 500 E debuted in 1990, but our specimen was manufactured in April 1992 and met its first owner in Hamburg. It arrived in Russia five years later and has since been fully restored to its original glory this summer.

The BMW, a year younger than the 500 E, belongs to the E34 M5 series that started in 1988. However, it received a significant upgrade shortly after the release of the five-liter Mercedes, with enhancements added in 1992. Thus, our sedan, assembled in September 1993, showcases an improved version of the M5, featuring a more powerful S38B38 engine and the Nürburgring Pack, which includes adaptive electronically controlled dampers, wider rear wheels, and Servotronic steering assistance.

These thirty-year-old classics, in showroom condition, are every enthusiast’s dream. However, the price for their eternal youth is steep. Today, both the BMW M5 and Mercedes 500 E in comparable conditions fetch prices similar to those in the early ’90s: between $60,000 and $80,000. But since age today is just a number, let’s save the credentials comparison for later. To the eternally young, the road beckons. Let them prove themselves. But first, they must be weighed.

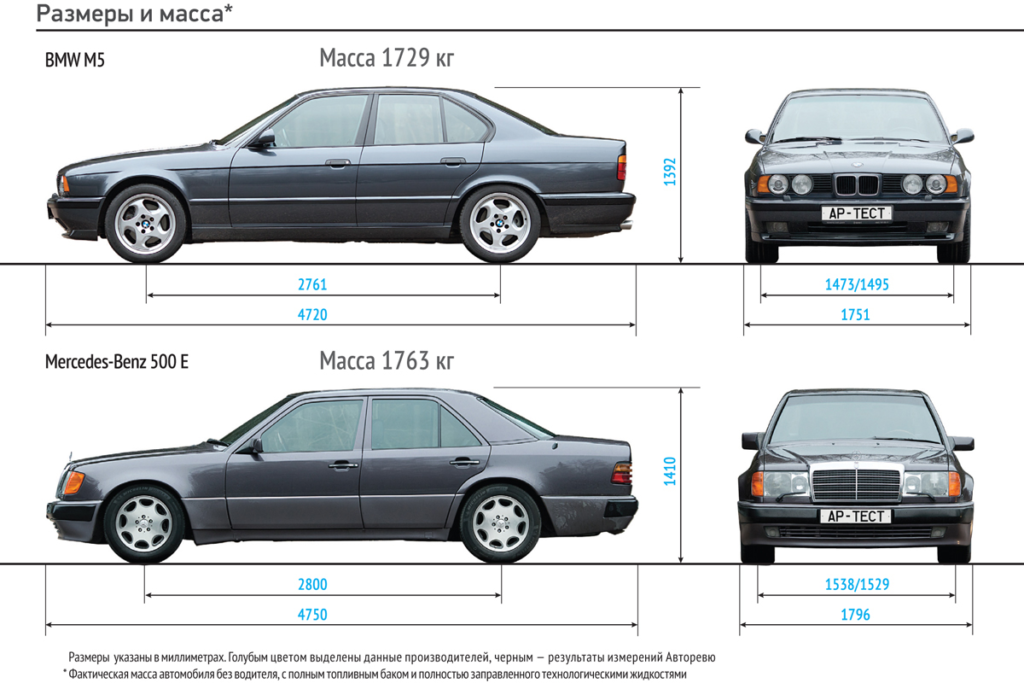

Weighing before the test not only verifies the specifications but also tests one’s judgment. The ‘124’ looks compact and refined, the E34 lean and toned, as if there’s nothing superfluous about their design or build. The term “light” comes to mind, but that’s not quite right. Both sedans tip the scales at seventeen hundred kilograms. The Mercedes weighs 1763 kg with a full 90-liter tank (excluding the driver), with 53% of that weight on the front axle. The BMW is slightly lighter by about thirty kilograms, despite having two fewer cylinders, a manual transmission instead of an automatic, and an 80-liter tank. Yet, its axle load distribution is nearly perfect.

It’s interesting that the S38 engine for the M5 E34, which cost about as much to produce as an entire BMW 316i, was mentioned in passing in the anniversary edition of “The Century of BMW.” This later S38B38 variant also entered history as the largest six-cylinder engine BMW has ever made. It featured an iron block combined with a 24-valve head, and unique aspects of the 3.8 version included electronic ignition with individual coils, a dual-mass flywheel, lightweight pistons, and enlarged 50 mm throttles.

The BMW’s inline-six, 3.8-liter engine cranks out 340 hp, giving it a significant power-to-weight advantage: 5.1 kg per horsepower (or 196.6 hp per tonne). The Mercedes’s five-liter V8 delivers 326 hp, with each horsepower moving 5.4 kg (or 184.9 hp per tonne). However, the torque figures tell a different story: 400 Nm from Munich versus 480 Nm from Stuttgart. And it’s crucial to utilize this power while the roads still resemble dry asphalt.

Mercedes didn’t immediately learn how to show off in the engine compartment. Beneath utilitarian plastic hides a beautiful manifold and dual-cam heads with variable intake timing. The M119 engine was developed for the 500 SL roadster, but in the 500 E sedan, it gained electronic injection and produces more torque (480 Nm instead of 450 Nm). Notice: the air intake is through the headlights, because the gaps around them create the highest pressure.

That morning, I initially chose the Mercedes. Its charisma is richer, its large, wide-open headlights radiate positivity. The upward tilt of the orange turn signals suggests a cheerful disposition, but the broad shoulders of the front fenders hint at a deceptive robustness. The aesthetics of the ‘124’ are enchanting. Its body panels drape like fabric, concealing power underneath, tightly conforming at the roof and pillars but flowing more freely below. Only the wheel arches protrude under this ‘cover,’ hinting at the force contained within.

Surprisingly, the “five-hundred” sits on mere 16-inch wheels. Factory 225/55 R16 tires were standard on all 500 Es, except for the limited Evo version, which came with 17-inch wheels.

It’s surprising, but this conservative business “office” copes well with the role of a pilot’s workplace. There are almost no miscalculations in basic ergonomics, and the steering wheel is even shorter than BMW’s: 2.9 turns from lock to lock.

It’s also surprising to find a contoured seat in an older Mercedes, offering both lateral support and thigh bolsters for comfort, although the leather is a bit slick. The steering wheel adjusts only for reach, electronically. The gauges are typical of a regular W124 ‘three-hundred,’ distinguished only by the yellow gear indicators on the speedometer and a tachometer redline that starts 500 rpm sooner—not later—than the base Mercedes.

Both cars are equipped by default with Recaro sport seats. In the Mercedes (first slide), they are slightly more laid-back but feature electric adjustments with memory (second slide), while in BMW (third slide), the seats are stricter and more functional.

The engine awakens loudly. The automatic transmission’s lever clicks quietly into ‘D,’ and the “five-hundred” smoothly pulls away in response to the accelerator. The steering is fairly light and feels empty at the center, but gains a pleasant reactive force in turns. The automatic tries to keep pace with the throttle. The suspension is soft, and I realize I may have been wrong about the Wall Street wolf. In its everyday life, this Mercedes clearly prefers private psychotherapy sessions.

The legendary Mercedes automatic transmission W4A028 is used here in the 722.365 version with a final drive ratio of 2.82. The slider to the left of the selector switches between sport mode and economy mode and vice versa.

Are you nervous about piloting a legendary super sedan on summer tires through puddles, with temperatures hovering around freezing? Relax and remember, a Mercedes remains a Mercedes, even if it’s fine-tuned in partnership with Porsche. Notice how the chassis responds calmly to steering input? How smoothly the suspension glides over the testing ground’s cobblestones on its way to the dynamometer? See, there’s nothing to worry about; it’s all predictable and safe.

Feeling reassured? Excellent. Now, press that pedal and smash it to the floor. Accelerate!

Wow, the transformation in the 500 E is always unexpected. I spent half the day driving it and was still amazed every time I floored the pedal. The range of temperaments in this sedan is incredibly wide.

The Mercedes launches forward, its nose lifting slightly after a brief hesitation at the start. A pulsating, infrasound roar fills the cabin and seems to resonate through the wooden dashboard like an expensive speaker. It’s like having the perfect sound system.

The instruments do not focus attention on the outstanding engine. Yellow marks on the speedometer are the gear boundaries: third gear—up to 180 km/h, and there are only four gears in total.

Finding the driest spot, I managed to measure the acceleration without the non-deactivatable ASR traction control system kicking in. The initial surge reached up to 0.9g. The engine revved to 6000 rpm, staying within the redline. Gear shifts were timely and precise. The 500 E accelerates to nearly 80 km/h on first gear, and up to 120 km/h on second. It’s thrilling and vivid, though the numbers reveal it wasn’t quite as fast as it felt. From standstill to 60 km/h took 3.5 seconds, and to 100 km/h took a flat seven seconds. From 100 to 200 km/h, the best run took 21.5 seconds. But pushing it further became a bit frightening.

Beyond 150 km/h, the Mercedes somehow loses stability and begins to sway from side to side. Oh, how I long for that reassuring coach who had instilled such calm just minutes before, but now the 500 E seems unsure of how to regain its composure. The relaxed responses now require me to grip the steering wheel tighter than I would like. Delays and body rolls start to manifest, followed by sporadic traction hiccups, as if there are misfires in one of the cylinders. We decided against attempting a max speed run, especially since the top speed is electronically limited.

Mercedes allows for sliding in brief phases when ASR has not yet had time to wake up. But how delightful it is to sink into a skid and how obediently it comes out of it! By the way, this frame clearly shows why the “five-hundred” needs such wide wheel arches.

Now, M5, it’s your turn to show how it should be done.

Have you ever noticed that the BMW E34 never smiles? It’s always focused on the result, and all its lines converge at the front, pointing where the headlights are aimed. It’s already mentally ahead, has traversed the path, and waits for you to perform just as well, if not better. That’s the essence of its focused gaze.

Thomas Ammerschlager, the chief engineer of BMW Motorsport, said that the M5 does not need “accelerating cosmetics.” But special wheels have always been a fetish for M versions. Initially, E34s were fitted with composite Turbine M wheels with a fan effect, and for the 3.8 engine version, a set of Throwing Star wheels by the legendary firm Otto Fuchs appeared. They also ventilate the brakes. But few know that the iconic “stars” are actually caps over forged five-spoke wheels.

The interior is designed with the same philosophy: everything converges on the driver. Coming from my E39, I feel almost at home here. Almost, because unlike the E39, the E34’s steering wheel doesn’t adjust for reach, and the climate control panel is cluttered with variously sized buttons and sliders. However, the seat grips perfectly, the seating position seems even lower, and the shifter for the five-speed manual moves with more precision and a shorter throw than any other retro BMW I’ve experienced.

Buttons, arrows—and not a single cup holder. It’s a pity that the beautiful emblem on the steering wheel at that time was not compatible with an airbag. This functional perfectionism is celebrated by fans and journalists, but soon BMW will learn to add a sense of wealth and luxury to the interiors. And then decide that, besides them, nothing else is needed.

In everyday life, the M car isn’t a psychotherapist but a motivational coach. It calms by doing the opposite. Feeling burnt out? Turn the key and reignite from the glow of the instrument backlighting. Not in the mood? Push the accelerator a couple of times and listen to the sound of life’s thirst. Confident and think you can handle everything effortlessly? Ease off the clutch and challenge yourself again.

There’s no ambiguity here. The BMW drives with a firm, precise grip from the start. The steering is heavy, always filled with effort, reactions are instantaneous, and body roll is virtually nonexistent. The M badge lights up the dashboard, the speedo goes up to 300 km/h, and the only driving aid is an adjustable auto-dimming rear-view mirror.

Now, under the first drops of rain, we’re on the same straight, trying to catch up with the swiftly fading autumn and outpace the Mercedes.

For the facelifted M5, the engine displacement was increased from 3.6 to 3.8 liters, enhancing torque at low and mid revs. However, there’s still a lack of pull below 4000 rpm. Ideally, you’d start at five thousand rpm, but the rear wheels invariably spin, so I dial it back to 3500 rpm and release the clutch a bit more gently than necessary. We’re hooked. The sound isn’t just filling the cabin; it’s piercing through it, from the engine block to the exhaust pipe.

The tachometer needle dances between 5000 and 7500 rpm. After reaching 140 km/h, a whistling noise starts near the front roof pillar—you can feel the air resistance trying to push the car off course, but the M5 maintains its trajectory far more accurately than the Mercedes. At 220 km/h in fifth gear, the acceleration ceases only after the speedometer reads 260 km/h. In reality, that’s 247.8 km/h. This is where the M5’s electronic limiter should engage, but the engine approaches it so gently it feels as if it could go further.

In the best attempt, the M5 just edges out the “five-hundred,” albeit symbolically: 6.9 seconds to 100 km/h and 15.9 seconds from 100 to 200 km/h. Peak accelerations are higher (1.0g), but there’s no jaw-dropping effect from the acceleration. There’s no werewolf effect. Instead, the transformation occurs at the very start of each drive, not during acceleration. That’s what sets it apart from the Mercedes.

Both cars have lost about a second from their passport data. It’s easy to attribute this to the weather, but I was intrigued by the M5’s throttle actuation, behaving as though it has an electronic gas pedal, though it’s actually linked to individual throttles by a metal cable. Yet the response is still dampened, and for throttle blips, you need to hold down the pedal a bit longer than usual.

Surprisingly, the M5 3.8 isn’t fond of drifting. It’s hard to believe, but even on wet asphalt, it requires deliberate provocation to lose traction; otherwise, the front wheels tend to slide first. To initiate a drift, the full thrust needs to be directed to the wide rear wheels—and keep the revs up to avoid the tires regaining traction and the M5 stabilizing itself. Despite a “shortened” differential, the M5 still features a long steering ratio (3.25 turns lock-to-lock) and a limited steering angle compared to standard E34 models due to the wide tires. These observations might prompt a reevaluation of those iconic Tbilisi drifting scenes.

Conversely, the Mercedes turned out to be pleasantly prone to drifting. Its engine displacement and torque are sufficient to induce rear wheel spin, but this is briefly curtailed by the non-deactivatable ASR system. It’s a shame, as the W124 initially responds at its limits with rear-end sliding. In situations where ASR lags, the Mercedes readily allows the driver to take full control. Without the electronics, it would be a thrilling and responsive car—a werewolf restrained.

Yet, the BMW truly possesses a magic that makes you exclaim “wow.” This stems from the EDC suspension with electronically controlled Boge dampers. There are only two modes: “Sport,” which provides a firm M suspension that restricts unnecessary movement, and “Adaptive,” which allows the dampers more freedom to smooth out road imperfections. While not as soft as a Mercedes, this setup approaches the comfort necessary for everyday driving.

I realized that the most unexpected but logical conclusion from the test is this: the BMW M5 is perfect for a role you might assume suits the Mercedes. It’s a werewolf that doesn’t need high revs to transform. The M5’s magic activates instantly, ensuring that even without reaching a track or autobahn, you still experience a transformative charge. It energizes with composure, motivation, and the drive to move forward—an indispensable coach for everyday life.

The five-seat cabin was offered in later E34 M versions (first slide), while early versions had a console in the middle of the rear seat, similar to in a Mercedes. The “five-hundred” (second slide) was always strictly a four-seater because all the space under the center cushion was occupied by a large differential from the 500 SL roadster.

In daily life with the Mercedes, we might both find it somewhat mundane. It’s a volcano that thrives on the ease of transforming into a monster, yet such transformations require space and the chance to accelerate fully at every light. Thus, if choosing…

Trunks are the last thing such cars should compete in, but here Mercedes (second slide) has the edge in volume, while BMW (first slide) wins in practicality: a net, side boxes, a hatch in the backrest, and a toolset were included in the standard equipment.

Let’s be frank. Cars like these are rarely the sole occupants of a garage, and their owners don’t typically need to choose just one. In my view, the ideal garage would accommodate both these vehicles. Indeed, this reflects the value of the era that birthed the M5 and 500 E—BMW and Mercedes were rivals then, each pushing the other, but neither imitating nor duplicating. They created vehicles capable of transforming into anything, yet remaining unmistakably themselves.

Dimensions and weight

Dimensions are in millimeters. Manufacturers’ data are highlighted in blue/Autoreview measurements are highlighted in black. Actual vehicle weight without driver, with full fuel tank and full process fluids

| Specification | BMW M5 | Mercedes-Benz 500 E |

|---|---|---|

| Body Type | Four-door sedan | Four-door sedan |

| Number of Seats | 5 | 4 |

| Trunk Volume (liters) | 460 | 485 |

| Curb Weight (kg) | 1725 | 1710 |

| Gross Vehicle Weight (kg) | 2150 | 2160 |

| Engine Type | Gasoline, with distributed injection | Gasoline, with distributed injection |

| Engine Position | Front, longitudinal | Front, longitudinal |

| Number and Configuration of Cylinders | Inline 6 | V8 |

| Engine Displacement (cc) | 3795 | 4973 |

| Number of Valves | 24 | 32 |

| Cylinder Diameter/Stroke (mm) | 94.6/90.0 | 96.5/85.0 |

| Compression Ratio | 10.5:1 | 10.0:1 |

| Maximum Power (hp/kW/rpm) | 340/250/6900 | 326/240/5600 |

| Maximum Torque (Nm/rpm) | 400/4750 | 480/3900 |

| Transmission | Manual, 5-speed | Automatic, 4-speed |

| Drive Type | Rear-wheel drive | Rear-wheel drive |

| Front Suspension | Independent, coil springs, McPherson | Independent, coil springs, McPherson with separated spring and shock absorber |

| Rear Suspension | Independent, coil springs, semi-trailing arms | Independent, coil springs, multi-link |

| Tire Size | 235/45 R17 | 225/55 R16 |

| Maximum Speed (km/h) | 250* | 250* |

| Acceleration 0—100 km/h (s) | 5.9 | 6.1 |

| Fuel Consumption, mixed cycle (l/100 km) | 12 | 13.5 |

| Fuel Tank Capacity (liters) | 80 | 90 |

| Fuel Type | Gasoline AI-95 | Gasoline AI-95 |

Photo: Dmitry Pitersky

This is a translation. You can read an original article here: Оборотни максимальной мощности: Mercedes-Benz 500 E и BMW M5 на полигоне

Published July 18, 2024 • 15m to read