I have been collecting literature on automotive history for a long time, and my 1:43 scale model collection is approaching a thousand pieces. These drawings were made to order for my upcoming book on Italian automotive design from 1948 to 1973, spanning the first post-war years to the beginning of the oil crisis. It was a golden era when true masterpieces were created by great people, including two key but underappreciated figures: I am convinced that post-war automotive design developed the way it did thanks to the wealthy industrialist Piero Duzio and aviation engineer Giovanni Savonucci.

Piero Ettore Duzio was a playboy—in the best sense of the word. Nearly a contemporary of the 20th century (born on October 13, 1899), he hailed from a very wealthy family in Turin: while the Agnelli clan owned the area to the right of Piazza San Carlo, the Duzio family mainly owned the left side. In his youth, Piero was a footballer, playing for Juventus, and when he injured his knee, the club’s owners supported him by hiring him as a sales representative for a Swiss textile company. He proved to be highly talented, selling more in his first week than his predecessor had in a year. In 1926, Duzio opened his own textile company and became the first in Italy to produce oilcloth. Later, he turned to banking and then started manufacturing tennis rackets and bicycles under the Beltrame brand. Finally, he founded the company Compagnia Industriale Sportiva Italia, or simply Cisitalia.

And yes, Piero was a passionate car enthusiast.

On the left is driver and test pilot Piero Taruffi, in the center is Piero Duzio, and to his right is Giovanni Savonucci.

Jacosa and Tubes

In 1929, Duzio entered his first Maserati in amateur competitions, later advancing to the major Grand Prix events. In 1938, at the Mille Miglia marathon, he finished third overall as part of the Alfa Romeo factory team, led by none other than Enzo Ferrari.

Duzio had been considering building his own racing car even before the war, and he decided to create what we now call a “monocup”—races with identical cars, where the skill of the driver decides the outcome. Duzio had no financial issues (after all, since 1932, his company had been supplying uniforms to the Italian Fascist army)—and while American bombers were attacking Turin, the famous Dante Jacosa, Fiat’s chief engineer, worked in the evenings at Duzio’s villa, developing an innovative spaceframe tubular chassis for an aluminum-bodied Cisitalia car.

Initially, Jacosa intended to use the chassis from his own creation, the Fiat Topolino. However, he later decided to use only its engine—of course, in a more powerful version with a dry sump—and some of the car’s components. The rest of the frame was designed from scratch in the style of the ultra-light pre-war BMW 328 Mille Miglia. After all, Duzio’s factory made not only bicycles but also airplane cabins and had experience working with pipes. They managed to source the chromoly steel tubing for the project. While the spaceframe of the BMW 328 MM weighed 103 kg, Duzio’s “cage” for the new car was four times lighter!

When the country returned to peacetime, Jacosa didn’t want to leave Fiat. However, he recommended Giovanni Savonucci, the head of Fiat’s aviation department, as a talented engineer for Duzio. In his unique style, Piero Duzio offered him the position of chief engineer, with a salary ten times higher than at Fiat. And so, from August 1945, Savonucci’s workplace became Cisitalia.

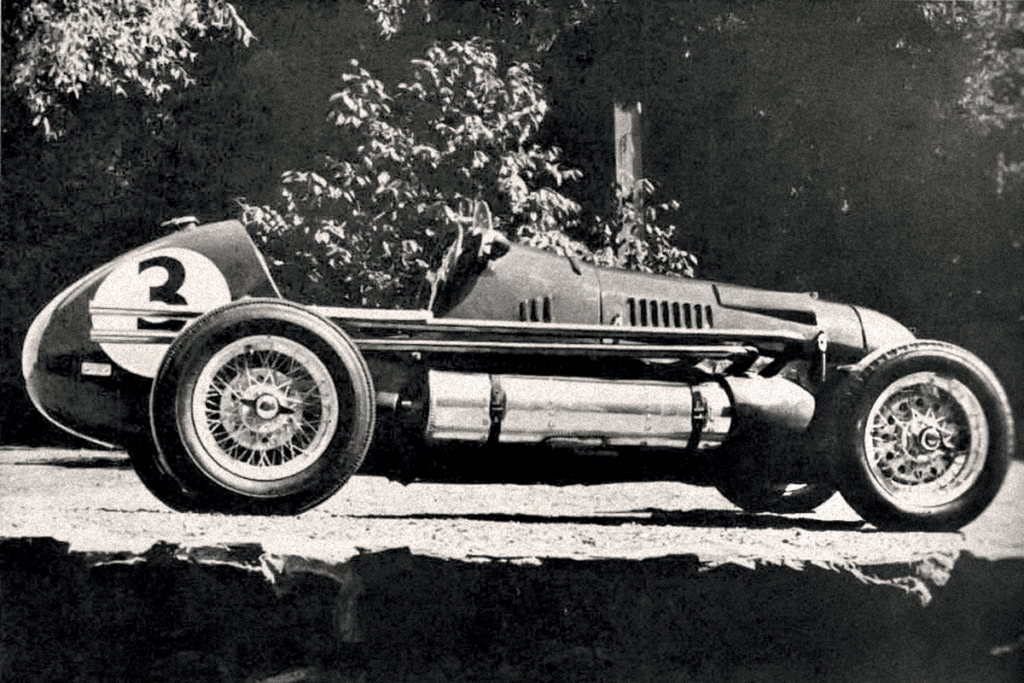

The Cisitalia D46 weighed only 400 kg. The gearbox was a three-speed, with semi-automatic shifting: the first and reverse gears were engaged using a lever under the steering wheel, while the second and third gears were engaged sequentially after each press of the clutch pedal. Another feature was that the steering wheel tilted upwards to ease the driver’s entry and exit.

By spring 1946, the first single-seater prototype, the D46 (Dusio 1946), was ready. By August, seven cars had been built, and by September, they were all at the starting line of the first post-war race in Italy. This was not a monocup—among the other 19 cars was Enzo Ferrari’s first racing car, the Auto Avio 815. For the Cisitalia team, drivers included Piero Taruffi, who also tuned the D46, Louis Chiron, and the unbeatable Tazio Nuvolari—but leading them all was Duzio himself. This is the only case in history where a driver won a debut race behind the wheel of a car bearing the same name!

Wide and Low

It was the best possible advertisement—orders poured in, including for a two-seater version. Regarding this, Duzio told Savonucci: “I want a car that is as wide as my Buick, as low as a racing car, as comfortable as a Rolls-Royce, and as light as our D46.”

And Savonucci took on the job. A graduate of the Polytechnic University of Turin in industrial mechanics, Savonucci had previously worked as an assistant professor of aeronautics and applied mechanics. During the war, he served as a captain in the Italian army in Albania, then led a partisan resistance group and assisted the American Fifth Army in liberating Italy.

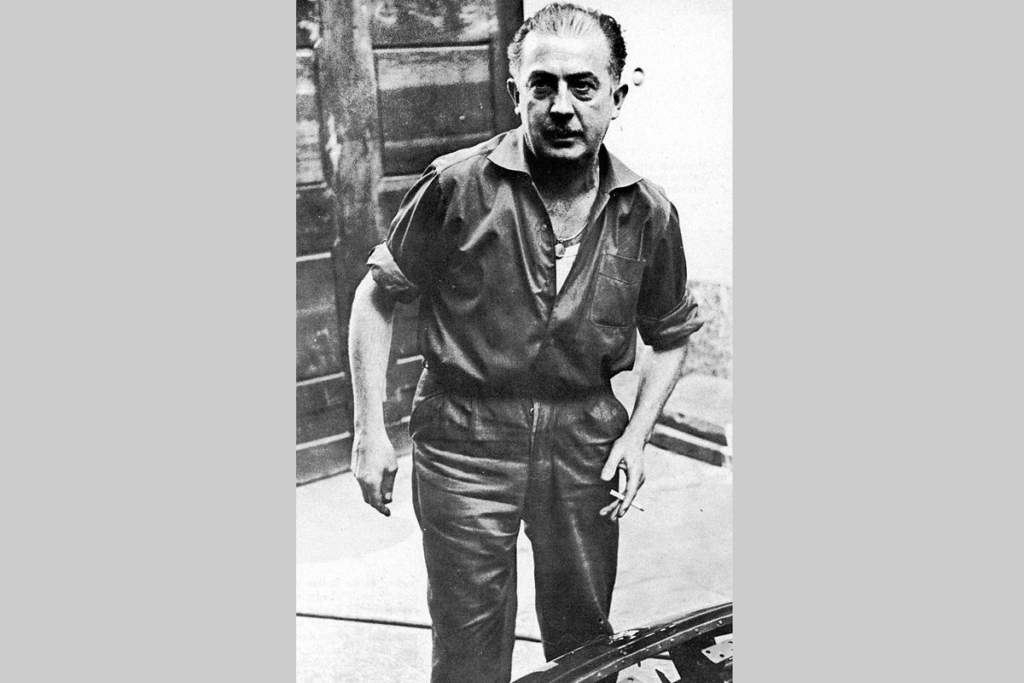

Giovanni Savonucci at work.

Under Duzio’s guidance, Savonucci’s talents were fully realized—it turned out Giovanni also had a sense of style, which was no surprise for a man from Ferrara, the cradle of the Italian Renaissance. For the chassis based on the spaceframe of the D46 racing model, he designed a coupe body that went down in automotive history as the Aerodinamica Savonuzzi. The order to manufacture two cars, later named the Cisitalia CMM (Coupe Mille Miglia), was placed with the Stabilimenti Farina company, owned by Giovanni Farina. Alfredo Vignale, who had worked there since 1939 and had a reputation as a metal artist, impressed Piero Duzio so much that he not only paid much more than the agreed price but also helped Vignale set up his own bodywork company, which in 1946 led to the creation of the Vignale atelier in Turin.

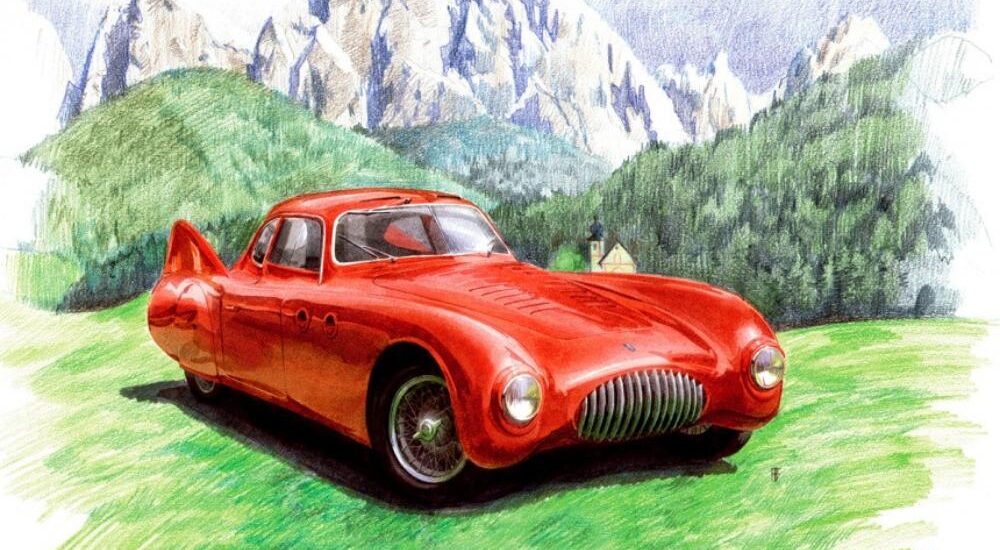

Cisitalia 202 CMM, 1947. The high rear fins provided stability at high speeds, working in conjunction with the rear spoiler installed above the rear window. The smooth contours and lowered rear end reduced air turbulence around the body. The hood was lower than the front fenders, a completely new element in design. Modern measurements of the drag coefficient showed an astonishingly low value of 0.29. The car achieved a speed of 200 km/h on the Turin-Milan highway, even with its small 1,100 cc engine.

Incidentally, the ventilation holes in the front fenders (two round ones on chassis 001/CMM and four rectangular ones on chassis 002/CMM) became a distinguishing feature of Vignale’s bodies. In 1949, similar side vents appeared on Buick cars.

But the Cisitalia CMM was a racing car, and Savonucci decided to create a production version based on it, to be sold to the general public. Thus, the Cisitalia 202 was born.

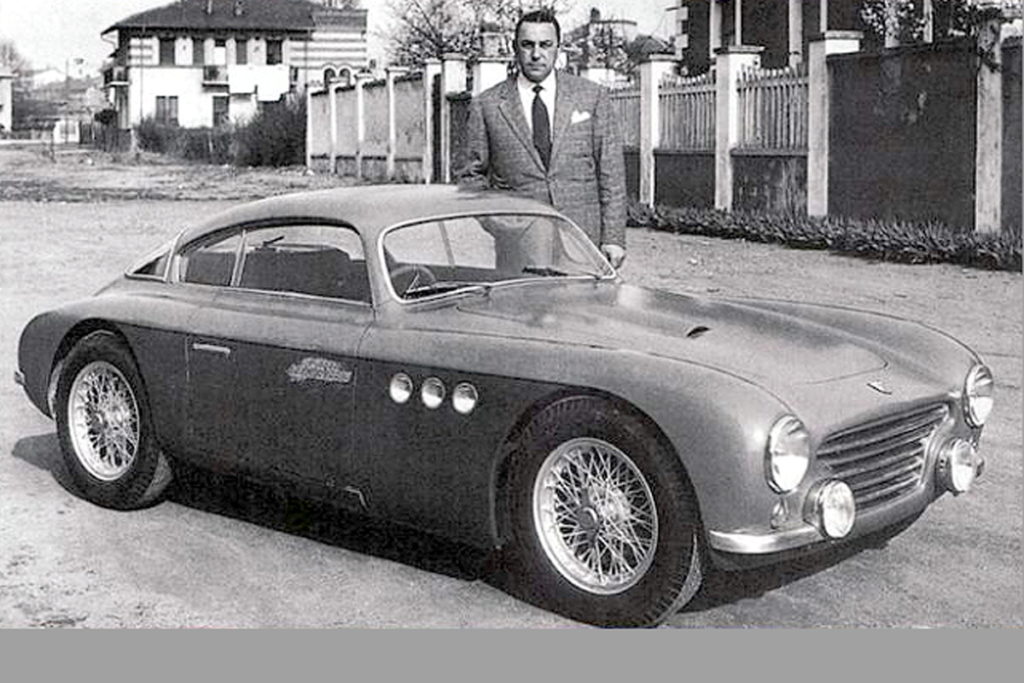

Alfredo Vignale at work. Even as the owner of a body shop, he did a lot of the work himself.

Alfredo Vignale posing with a Maserati 3500.

Savonucci removed the rear fins, increased the windows, shortened the rear section, and simplified the contours. The bodies, made from an aluminum-magnesium alloy called Itallumag, were to be produced at the Battista Farina atelier—Giovanni’s younger brother, nicknamed Pinin. In September 1947, Carrozzeria Pinin Farina began producing the Cisitalia 202 Sport Coupe.

Later, Savonucci publicly thanked Pinin Farina for the design of these cars. However, the style was entirely his work. And not just the style: Giovanni designed all the mechanics, supervised construction, and even acted as a test driver.

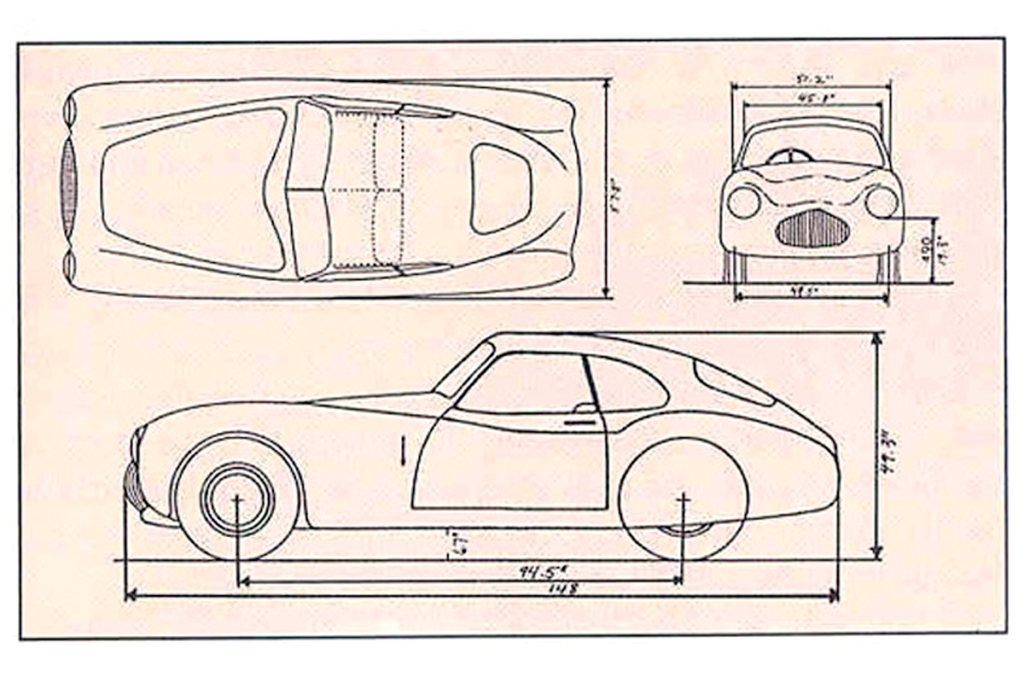

The first sketch of the Cisitalia 202, made by Savonucci.

The Cisitalia 202 Sport Coupe became the world’s first production car built on a spaceframe chassis—because Colin Chapman built his Lotus Mark VI only in 1952, and Ferrari and Maserati needed ten more years to develop similar constructions. For a coupe with a tiny engine producing only 50-60 hp, Duzio asked for more than dealers were charging for a Jaguar XK120 or Cadillac 62 Coupe at the time—$5,000! The open Cisitalia 202 from 1948 was even $2,000 more expensive. However, these elegant cars sold well in the United States—thanks to the famous dealer Max Hoffman, who successfully promoted German and Italian brands among the American elite. Only Henry Ford II bought two Cisitalia cars with different bodies.

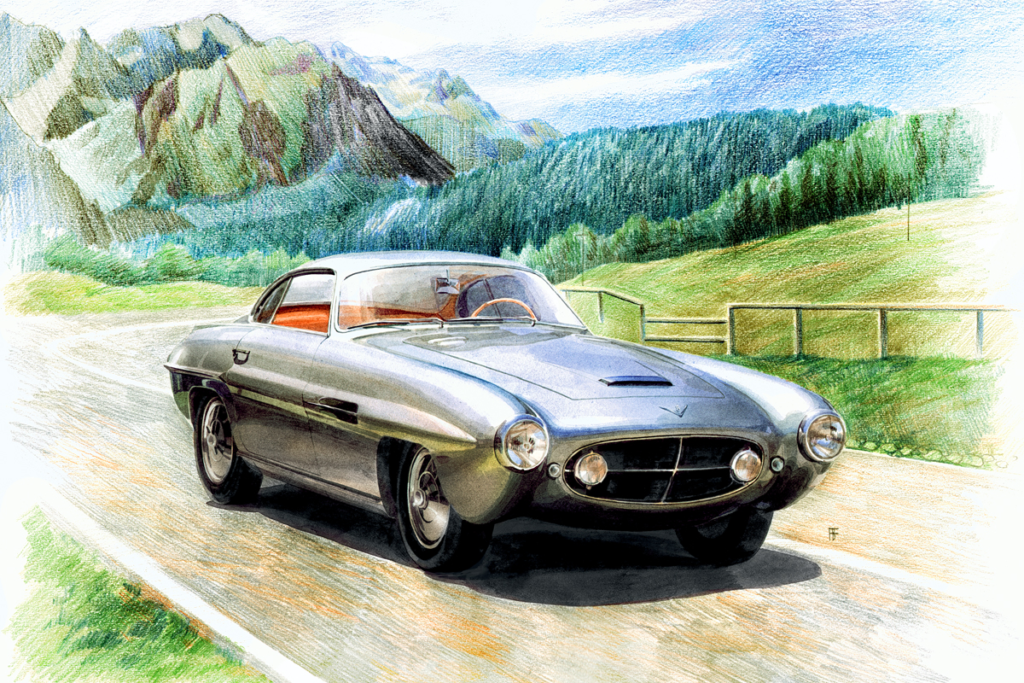

Cisitalia Tipo 202 Berlinetta, 1947. As conceived by Savonucci, the radiator grille was an irregular oval, filled with 23 polished aluminum vertical plates. The first bodies lacked side vents on the front fenders, but later, their number and shape varied from one oval to three round ones. Carrozzeria Pinin Farina replicated this body almost unchanged for the Maserati A6/1500—the atelier not only earned praise for the design, which belonged to Savonucci, but also copied it for another client!

Ironically, while Americans greatly admired Savonucci’s genius for simplicity in design, they didn’t adopt this form but instead became fascinated by his other invention—rear fins. These grew like bamboo, reaching their peak in the 1959 models.

It seemed that Cisitalia was on the verge of commercial success. However, instead of focusing on production and improving the 202 model, Duzio decided to invest in racing: he planned to build a winning Grand Prix car, which would later be the foundation for Formula 1.

The Price of Megalomania

The entire team tried to dissuade the owner. Savonucci himself believed the focus should have been on increasing engine power for the 202 model, not spending enormous sums on a supercar. He pointed to the pre-war “Silver Arrows”—Mercedes and Auto Union, which had developed under the patronage of Hitler’s regime with state support.

But Duzio responded unexpectedly to this argument. “Who designed Auto Union—Ferdinand Porsche? We need to hire him!”

The problem was, Porsche was in a French prison after the war for his cooperation with the Nazis. But money—and connections—could solve everything. Carlo Abarth, Duzio’s racing team director, was married to Porsche’s secretary. In December 1946, thanks to Abarth’s mediation, Ferdinand Porsche’s son, Ferry Porsche, traveled to Turin, met with Duzio, and received a check for one million French francs. Thanks to this money—and the support of famous drivers Chiron and Sommer, as well as journalist Faru—Ferdinand Porsche and his son-in-law Anton Piëch were released on August 1, 1947.

Duzio signed contracts with Ferry and his sister Louise Piëch even before their release. For the development of the Cisitalia 360 car, the rear-engine sports car Cisitalia 370, a synchronized gearbox, and even a tractor, the Porsche family was to receive 400,000 Austrian schillings, 10 million lira, and 11,000 US dollars. An additional half a million schillings was allocated for technical support.

However, the budget for the all-wheel-drive megacar based on the spaceframe chassis with a 12-cylinder boxer engine, equipped with two compressors, quickly exceeded expectations. The engine power was 500 hp on the test bench, and the calculated speed was approaching 400 km/h. But the financial situation at the company rapidly deteriorated. In April 1949, Duzio, sensing imminent bankruptcy, decided to move production to Argentina, where President Juan Perón had promised support.

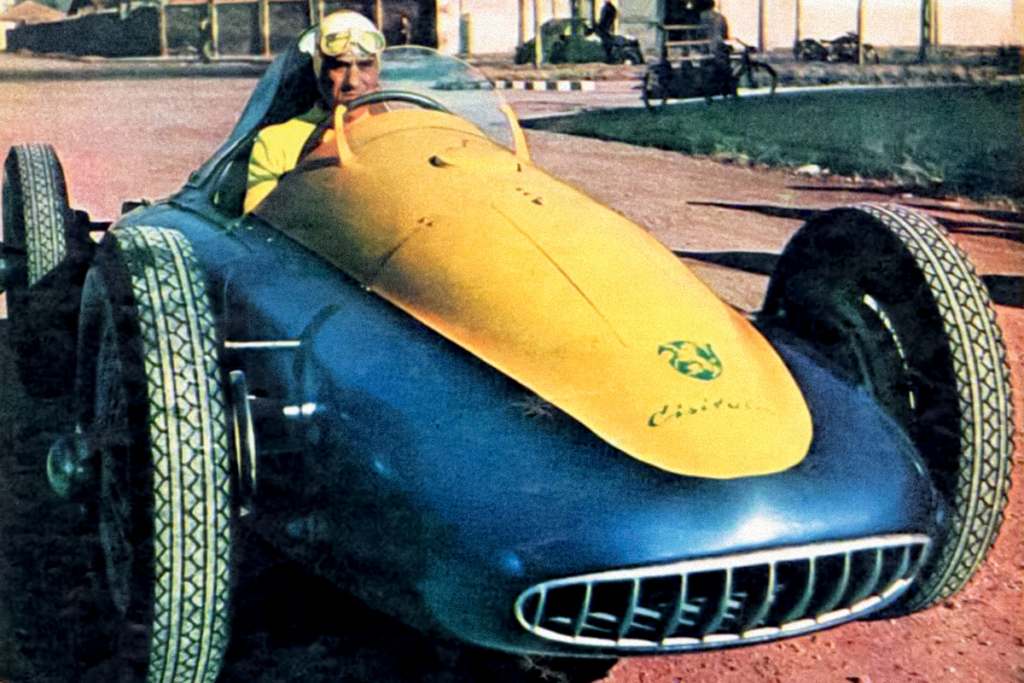

Tazio Nuvolari and the fateful Cisitalia 360 race car, prepared for shipment to Argentina and painted in national colors.

It cannot be said that Duzio was successful in the New World. While he opened a new factory, Autoar (Automotores Argentinos), and began assembling his cars under the Cisitalia brand, he later converted 3,000 military Willys jeeps into heavy-duty and practical seven-seat station wagons called Rural. His company, Cisitalia Argentina SA, also imported Italian machinery, built trucks, and manufactured agricultural equipment. However, the once-favored son of fortune was unable to reach the heights he had once enjoyed, though he did visit Italy and even participated in races. Piero lived until November 1975 and was buried in Buenos Aires.

To handle the challenges back home, Duzio entrusted his son, Carlo, who kept Cisitalia afloat until 1964. The company’s story did not end in bankruptcy but instead with debts paid off. However, the crankshaft from Hirth for the 12-cylinder engine in the Cisitalia 360, which had been the source of all the misfortunes, was symbolically thrown into the Po River by Carlo.

Abarth’s Straight Pipe

The collaboration with Porsche not only marked the decline of Duzio’s company but also led to the creation of the Porsche family’s first model, the Porsche 356 coupe, made possible thanks to Italian funding. Additionally, from the remnants of Cisitalia, Carlo Abarth built his own company—more precisely, from spare parts.

After Duzio Sr. moved to the New World, Carlo Abarth was compensated for his previous work with three finished Cisitalia 204 Sport cars, two in disassembled form, and several crates of parts. Among those parts were new-type mufflers that Giovanni Savonucci had designed to increase engine output, inspired by his study of… pistol silencers. The central channel, with a constant cross-section, had side outlets into an empty chamber filled with mineral wool, which reduced gas resistance and increased engine power. Most importantly, Savonucci allowed for sound tuning, enhancing or suppressing certain harmonics to achieve a more pleasing exhaust note.

Carlo Abarth carefully holds the muffler designed by Savonucci. The scorpion symbol, Abarth’s zodiac sign, is visible on it—his company’s emblem.

Carlo Abarth and his first car, the Abarth 205A, standing at waist height.

Carlo Abarth realized this was his moment—he established serial production of these harmonious mufflers. From 1949 to 1971, Abarth produced approximately 3.5 million units for 345 different car types. Thanks to this business, Abarth maintained his own racing team, and in the spring of 1950, he released his first car under his own name—the Abarth 205A, also known as the Abarth Monza. In essence, it was a modified Cisitalia 204A, but with significant changes to the chassis and engine. The body was ordered from the Vignale atelier, and its design was developed by Giovanni Michelotti—once considered a wunderkind, Michelotti worked as an assistant designer for Battista Farina from the age of 14, and in 1949, at the age of 28, opened his own studio.

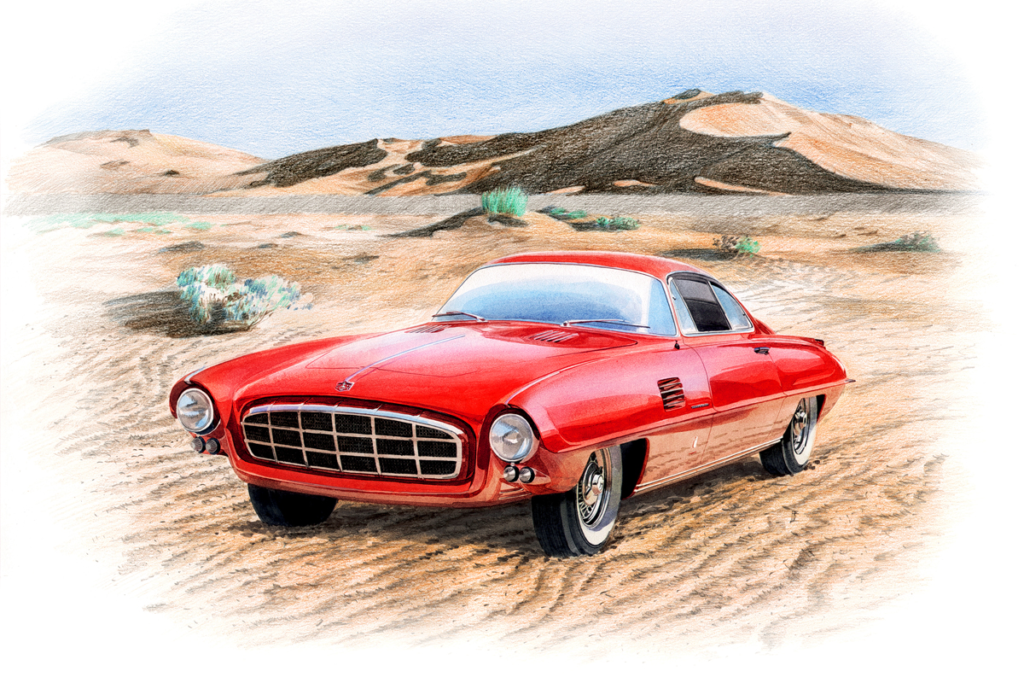

Abarth 205A Berlinetta, 1950, design by Giovanni Michelotti. The low body with a smoothly sloping roof, and three round openings on the front fenders, typical of Vignale bodies of the time. The first version was a lightweight model with an aluminum body, designed for the 1950 Mille Miglia race. It featured a tuned Fiat engine of 1,100 cc and was showcased at the Turin Auto Show in 1950. After a series of victories in European races, the car was brought to the U.S., where it was severely damaged in a garage fire in 1981. The drawing shows the car after restoration.

Can you feel how intertwined the fates of all these Italian automotive geniuses are?

What About Savonucci? Savonucci left the Cisitalia company in 1949, and not just because of financial troubles—he was repelled by Duzio’s collaboration with the Germans. Just recently, during the war, the SS had executed his brother, Alberto, who was closely connected to the partisan underground. And Porsche had been a favorite of Hitler…

Savonucci’s Supersonica

After leaving Duzio, Savonucci was commissioned by an American investor to design small racing cars like the Midget, which were very popular across the ocean. In 1953, together with Virgilio Conrero, his mechanic and test driver at the time, Savonucci conceptualized and brought to life the Alfa Romeo 1900 Conrero concept car. It featured a tubular frame with Lancia’s independent rear suspension—and a revolutionary “supersonic” design called Supersonica: Savonucci returned to the aviation theme, which was familiar to him not by hearsay.

The supersonic body was made in metal by the Ghia body shop, and the head of the atelier, Luigi Segre, was so impressed by Savonucci’s talents that he offered him the position of technical director—which Giovanni accepted in 1954.

Savonucci’s new design was an incredible success—for example, Fiat signed a contract with Ghia to supply 50 bodies for the 8V model. Segre also proposed a concept car in this style for Chrysler’s Idea Cars program. So, at the 1954 Turin Motor Show, the De Soto Adventurer II appeared next to the Supersonica—though the ideas from Savonucci were hurriedly adapted with the active participation of Chrysler’s chief designer, Virgil Exner. But due to its long wheelbase, the Adventurer II ended up looking disproportionate, resembling a hound dog—even the missing bumpers couldn’t help.

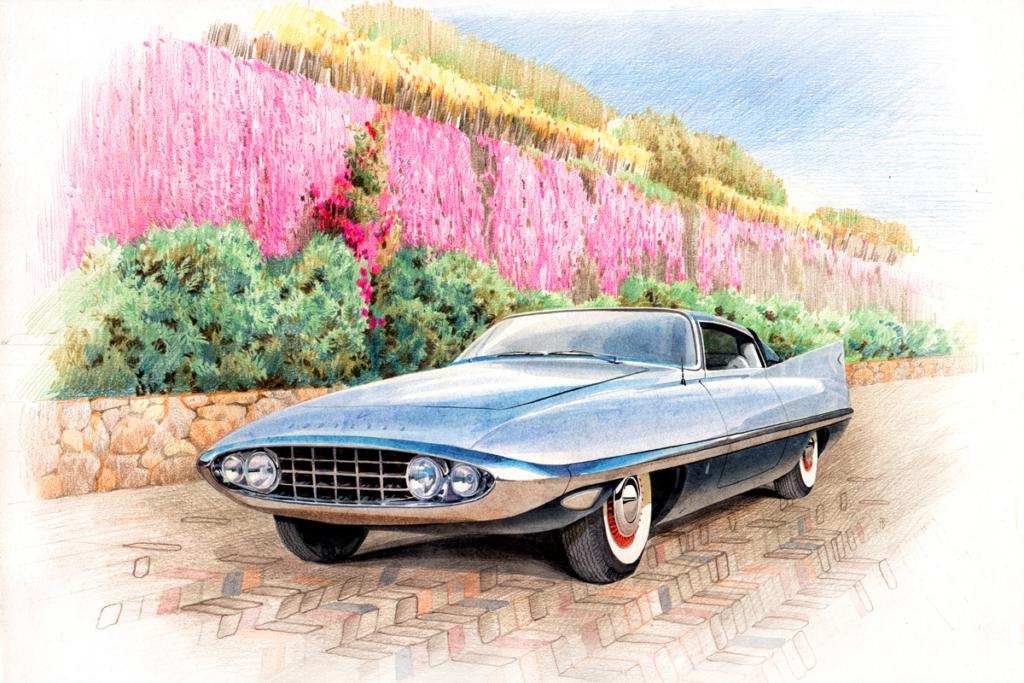

Fiat 8V Supersonic Ghia, 1953. The base was the Alfa Romeo 1900C Sprint, with additional parts sourced from Fiat 1400 and Lancia Aurelia. The long hood, extremely low roof, and rear lights styled like turbojet engine nozzles. The rear window and roof were covered by a large, curved panel of Perspex to create a light interior. The sharp edge starting above the front wheels and ending at the rear gave the silhouette its sense of speed.

Thus, the next concept car the Americans ordered from Savonucci was built from scratch, with only external dimensions specified. Using the aerodynamic tunnel at the University of Turin, Savonucci designed a super-streamlined body with vertical fins/stabilizers starting from the nose of the car. The name Gilda referred to the 1946 film noir of the same name, starring Rita Hayworth. The next Chrysler Dart concept car, built by Savonucci as part of the Idea Cars program, boasted an astonishing drag coefficient of 0.17!

De Soto Adventurer II Ghia, 1954. This concept car toured auto shows worldwide, and in Brussels in 1956, it was noticed by King Mohammed V of Morocco, who bought it for $20,000—about the same price as a new Rolls-Royce at the time. However, a week later, the king returned the car, claiming that the seat was too narrow for his royal rear.

Incidentally, the Dart was supposed to sail to America on the infamous ship Andrea Doria, but at the last moment, the shipment was postponed to the following month. This saved the car from sinking to the bottom of the sea—because the Doria sank off the coast of New York after colliding with the Stockholm, taking with it the Chrysler Norseman concept—an entirely functional car that had been built by Ghia over 15 months.

Chrysler Dart Ghia, 1957. The base was the Chrysler Imperial with a tuned 375-hp engine. The car had a 2+2 seating configuration, and a unique roof was specially designed for it—allowing the entire horizontal section to slide back under the rear window, or be completely removed, including the rear posts, turning the car into a convertible while in motion!

Later, Savonucci himself traveled to the United States, as such a talented automotive engineer and stylist, with experience in aviation, was an invaluable asset to Chrysler. Starting in 1957, he worked as the deputy chief engineer for automotive and gas turbine research for 12 years. Giovanni was happy to relocate after the tragic death of his second brother, Giorgio, in the mountains near Cortina d’Ampezzo—under mysterious circumstances: search efforts continued from July to November, but his body was never found.

Ghia Gilda, 1955. This concept car by Savonucci inspired Bruno Sacco, the future chief designer at Daimler-Benz, to become an automotive stylist.

However, in America, the general public was never introduced to Savonucci. All the glory went to his boss, George Huebner. Still, the Chrysler Turbine car with a gas turbine engine, of which 50 prototypes were made in Italy at Ghia and delivered to American families for testing, was quite impressive. In 1969, Savonucci returned to Italy: first as the head of development at Fiat, then as a consultant, a role he held until his death in 1987 at the age of 77.

Savonucci at home with one of the Turbines, ready for a shoot in the film The Lively Set (1964). Savonucci points to the car, hinting that it was his design.

Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote: “There is no history, only biographies.” Why did Duzio not trust his fortune, which had given him the Cisitalia 202 masterpiece, and instead desire the cursed Grand Prix car? Savonucci could have done so much more if he had stayed home, where he was a god of aerodynamic design. But both of them had an incredible impact on the modern automotive world. And that justifies all their mistakes.

Photo: author’s archive | drawings by Boris Fox

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: Истинные герои итальянского автодизайна: Дузио, Савонуцци и революционная Cisitalia

Published March 13, 2025 • 16m to read