Nestled along the scenic shores of Lake Constance in Friedrichshafen, Germany, the Zeppelin Museum not only chronicles the evolution of airships but also houses an impressive collection of vintage automobiles.

My fascination with early 20th-century aviation was modest, drawn mainly from illustrations in “Technology—Youth” magazine and tales of the adventurous pilot Utochkin. Yet, it was the memoirs of aircraft designer Yakovlev, replete with World War I aircraft tales, that sparked my youthful imagination. However, airships remained a mystery, their stories untold until my visit to this museum.

Dedicated entirely to the legacy of airships, the museum celebrates Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the pioneer who in 1900 launched his first airship, LZ1—marking the dawn of the Zeppelin era. After a devastating fire destroyed his fourth airship in 1908, public support enabled the count to establish Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, a company that thrives to this day.

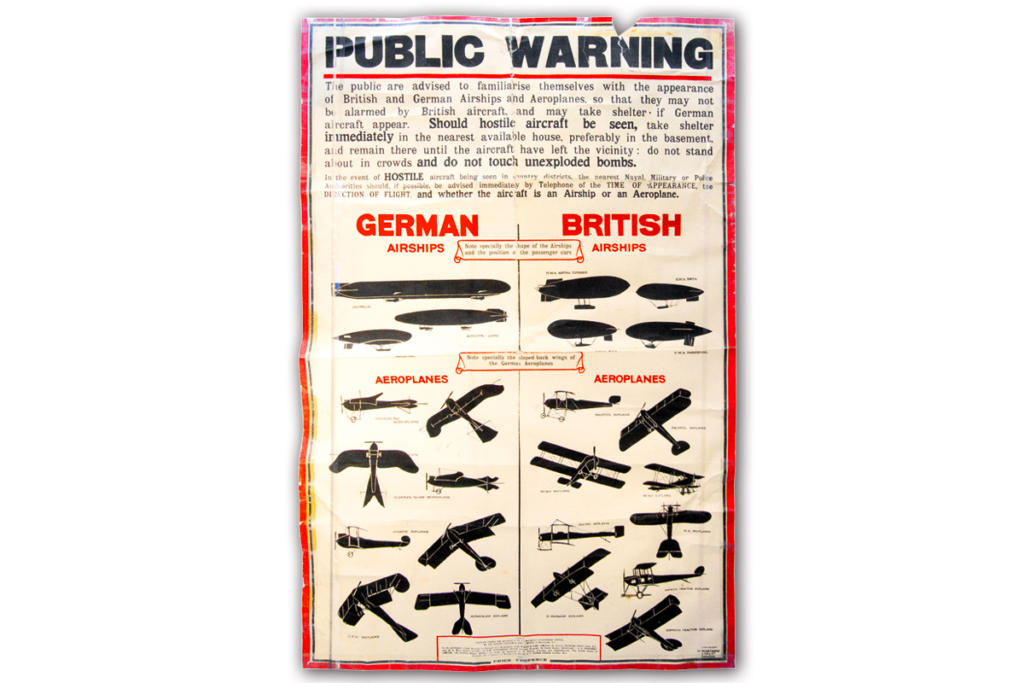

A World War I-era poster with silhouettes of aircraft. The long “cigar” in the top left corner is a Zeppelin.

Count Zeppelin’s ventures were supported by notable collaborators: Karl Maybach in engine manufacturing, Claude Dornier in aircraft development, and Zahnradfabrik Friedrichshafen, now known as the renowned ZF Group.

During World War I, the sight of a Zeppelin often signified impending doom. The museum features a wartime London poster, a haunting reminder of the fear they inspired, complete with silhouettes of German and British airships and warnings about unexploded ordnance.

The poet Maximilian Voloshin captured the ominous presence of these airships in his 1915 poem “Zeppelins over Paris,” portraying them as ghostly figures in the night sky.

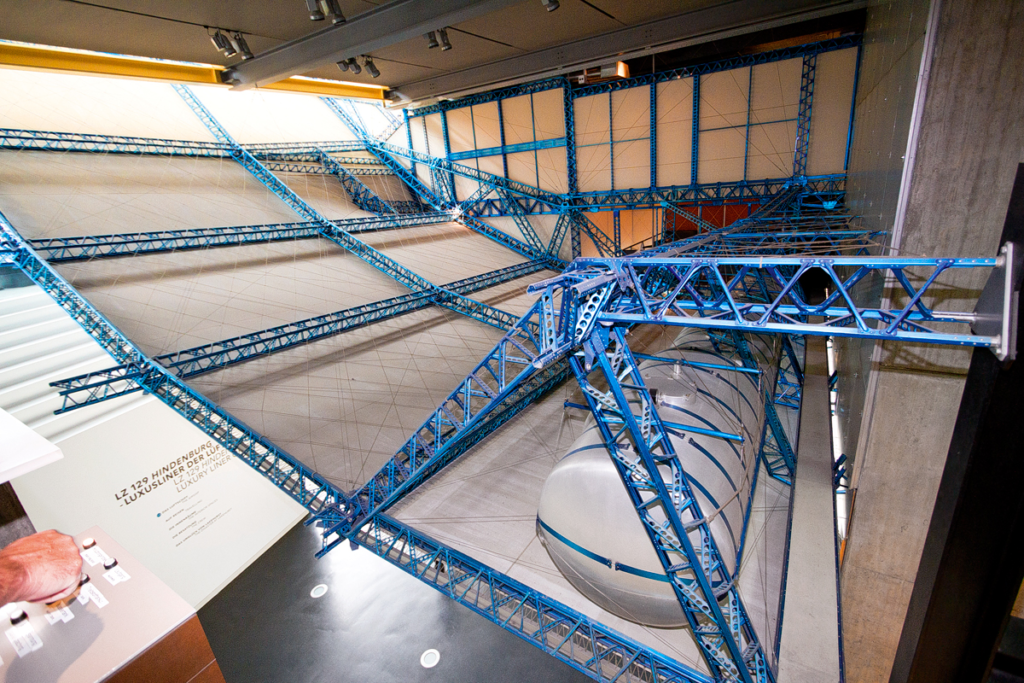

The Hindenburg under construction—what scale!

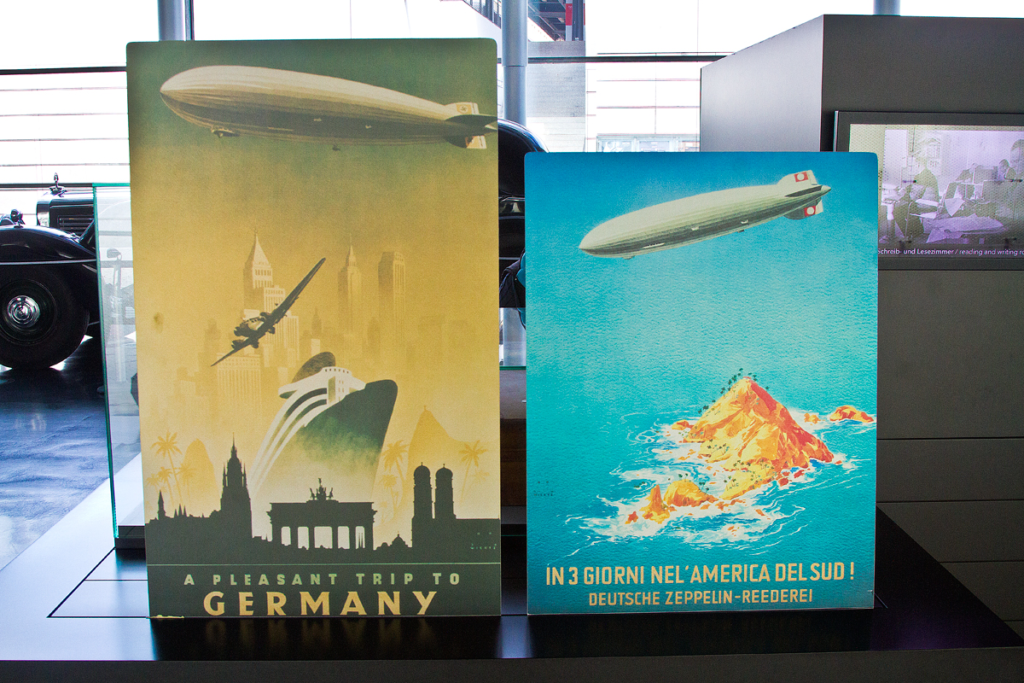

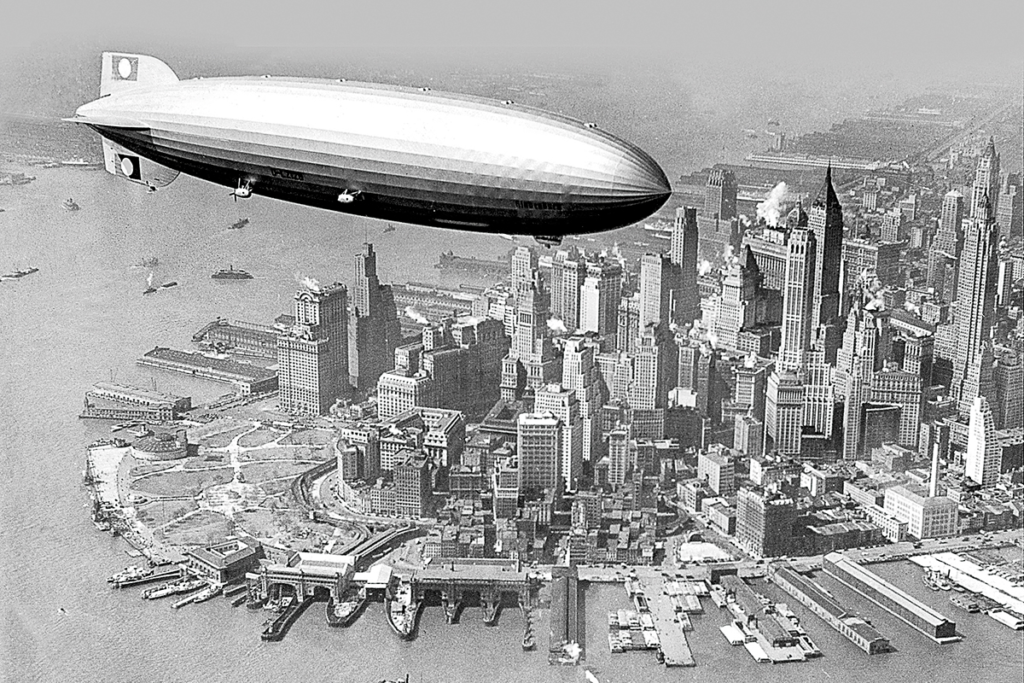

Transitioning from instruments of war to civilian marvels, Zeppelins evolved into the prototypes of modern airliners, traversing the skies and connecting continents. The famous LZ127, known as “Graf Zeppelin,” was particularly noteworthy, boasting 590 international flights, including 143 transatlantic crossings.

A cross-section of the Hindenburg: you can see the frame ribs, their cladding, and the fuel and water tanks. There were also 16 gas tanks inside the frame, but they are not shown.

A section of the frame: duralumin structure with rivets and cladding.

In 1930, “Graf Zeppelin” graced Moscow with a friendly visit, an event marred only by the tensions of the time, which saw the airship come under fire as it crossed the Soviet border. This incident did not deter the Germans, who took the opportunity to conduct aerial photography over Moscow, and later, a reconnaissance mission over the Soviet Arctic.

The zenith of Zeppelin grandeur was embodied by LZ129 Hindenburg, the largest airship ever built. The main exhibition at the museum features a replica section of the Hindenburg, complete with its original duralumin structure and interiors—a testament to its formidable presence.

A section of the frame: duralumin structure with rivets and cladding.

The Hindenburg’s lounge and a corridor with windows through which passengers viewed the ground.

Reading room.

Constructed over five years, Hindenburg dwarfed even the Titanic in scale and ambition. Powered by four Daimler-Benz diesel engines and capable of carrying 90,000 liters of fuel, it was a floating leviathan, filled with 200,000 cubic meters of hydrogen.

The Hindenburg offered luxurious accommodations for its passengers, who seemed undeterred by the potential dangers of flying in a hydrogen-filled behemoth. It featured 50 sleeping berths, expanding to 75 by 1937, and a crew complement of 50-60, mirroring the service of an ocean liner.

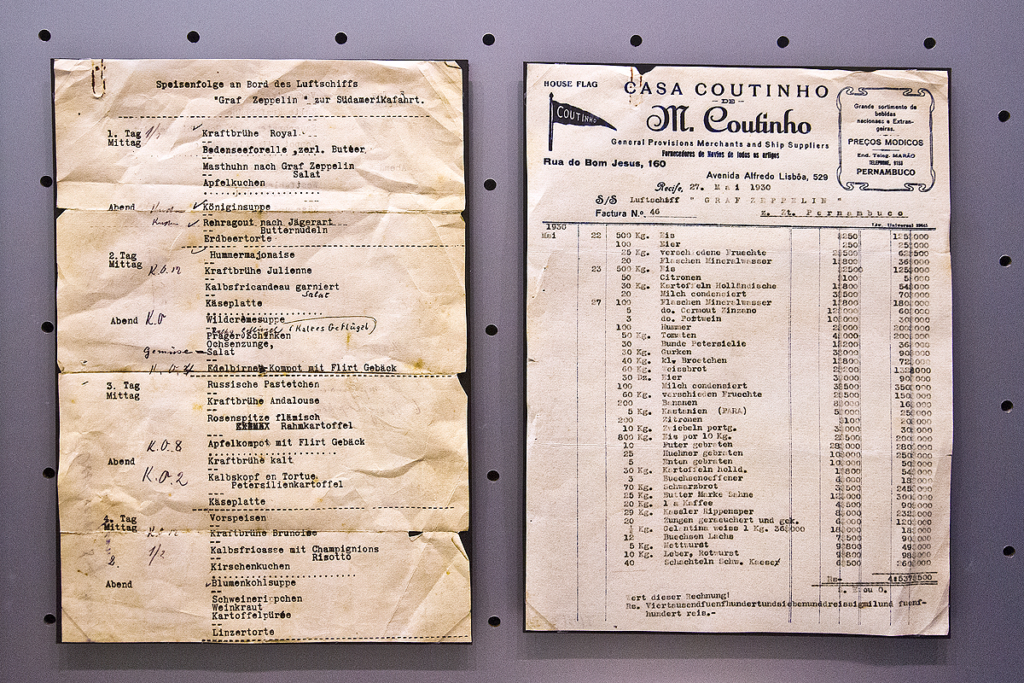

Tableware aboard the airship…

And the menu.

The opulence aboard Hindenburg extended to its amenities, which included a kitchen, expansive dining hall, lounge, bar, and even an aluminum-bodied piano. The museum retains memorabilia from those flights, including menus and black-and-white postcards depicting life aboard the airship.

The Hindenburg disaster on May 6, 1937.

Tragically, the Hindenburg’s story concluded on May 6, 1937, when it ignited while docking near New York. Out of 97 on board, 62 survived, marking a poignant end to the era of passenger airships. The remnants of this disaster, including a charred frame and a stopped clock encased in melted aluminum, serve as somber relics of a bygone era.

The Hindenburg’s clock in a melted casing.

Today, the legacy of the Zeppelins endures, not only in the stories preserved at the museum but also in their influence on modern aviation and the ongoing production of airships. A visit to this museum offers a profound glimpse into the ambitious spirit of early 20th-century innovation and the indelible mark it left on history.

As we venture deeper into the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen, beneath the grand Hindenburg model’s fuselage, lies a tribute not just to the skies but also to automotive engineering. Here stands the majestic 1938 Maybach DS8 Zeppelin sedan, a ground vehicle with a spirit akin to its airborne namesakes. Powered by a robust 200-horsepower V12 engine, this luxury sedan could reach speeds of 170 km/h and had a hearty appetite for fuel, consuming 28 liters per 100 km. Its transmission was a marvel of its era—an eight-speed Maybach Variorex with gear pre-selection, a system so advanced it was even used in German tanks!

The most luxurious of the pre-war Maybachs—the DS8 Zeppelin (1938).

Weighing nearly 3.5 tons, the DS8 Zeppelin required a driver with a heavy vehicle license, a testament to its substantial build. Priced at 30,000 Reichsmarks, this vehicle cost as much as two dozen contemporary Opel P4 sedans.

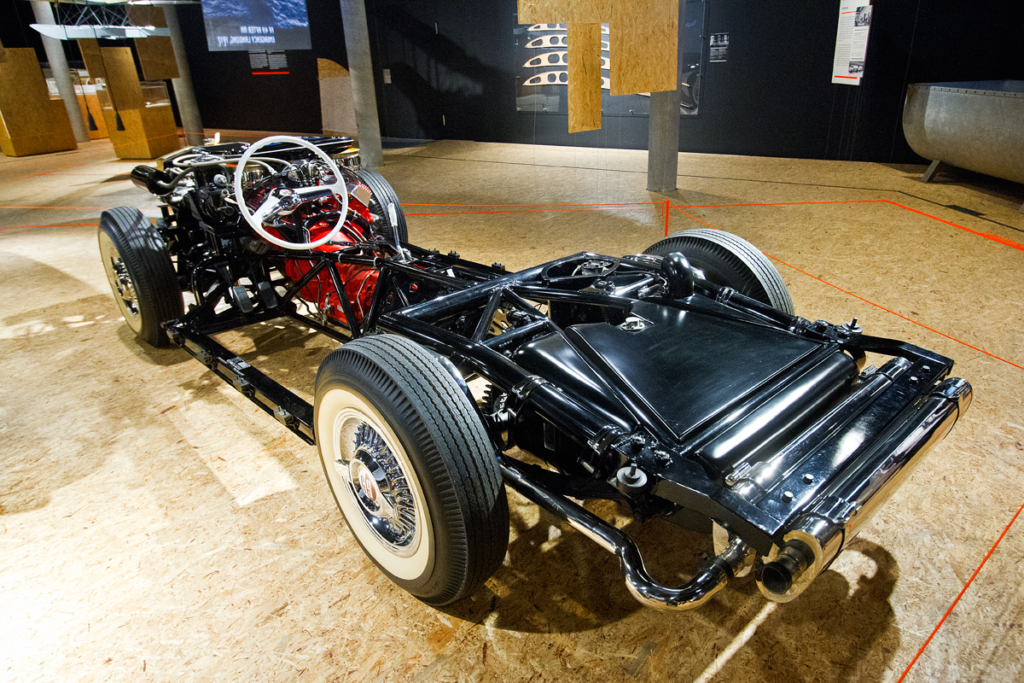

The chassis of the Maybach SW38 passenger car (1937). Both suspensions—front…

…and rear—are designed with springs and transverse leaf springs.

Yet, the Zeppelin Museum holds another automotive wonder, even more curious than the first—the 1957 Gaylord Gladiator from the United States, displayed in dual versions: one complete and one skeletal. But what does this American car have to do with German airships?

This Gaylord Gladiator, according to the factory plates, is the second unit and was built in October 1957.

This tale begins in post-war America with a wealthy entrepreneur named Gaylord, who made his fortune in ladies’ hair accessories. His sons, James and Edward, inherited their father’s passion and wealth, and their dreams were not of hair clips but of creating a spectacular car. They pursued this dream without restraint.

The father of the car’s creators made his fortune from ladies’ hair clips.

Their search for a designer led them to Alex Tremulis of Tucker fame, known for his work on the exotic three-headlight Tucker Torpedo. However, after a series of company changes, Tremulis passed the project to freelance designer Brooks Stevens, who had ties to Harley-Davidson and Studebaker.

The first model had “owl eyes”—two large Lucas headlights.

The design brief was to blend modernity with classic elegance, and the initial model featured striking “owl eyes”—two large Lucas headlights reminiscent of pre-World War II cars. This feature, however, was later replaced with four smaller headlights for a more refined look.

The body of one of the Gladiators on the slips in the Zeppelin factory.

Constructed from a tubular space frame plated in chrome and molybdenum, the Gaylord Gladiator was impressively lightweight for its time, tipping the scales at 1800 kg. It featured a traditional suspension setup but with modern tweaks like enlarged rubber bushings and lubricated rear leaf springs.

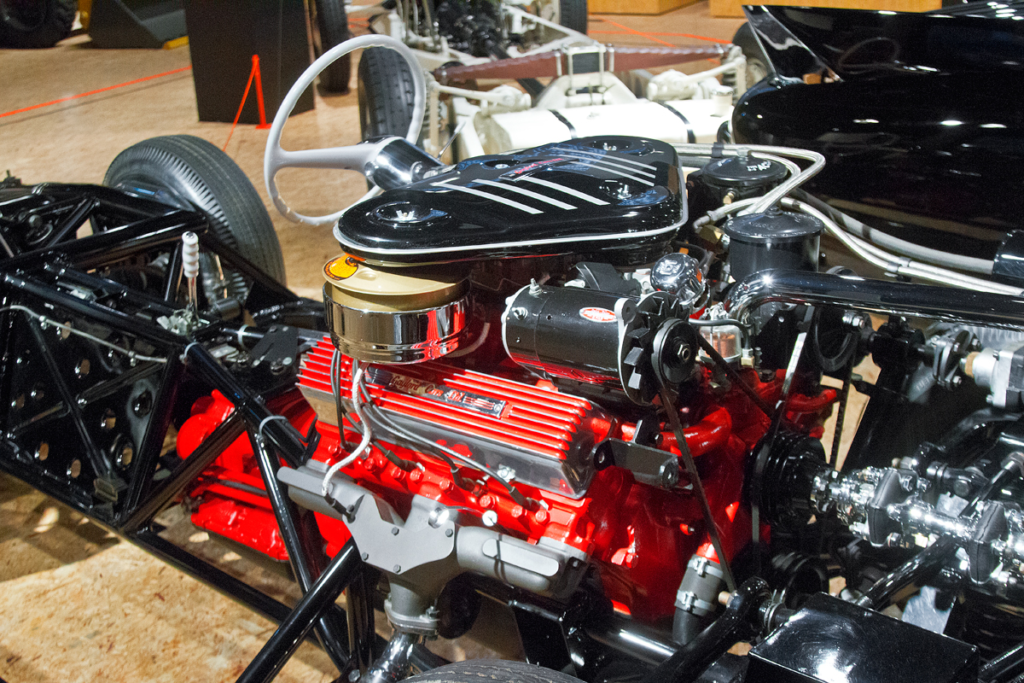

The Cadillac V8 engine (5.98 liters, 309 hp) could propel the car to 200 km/h.

Under the hood, the initial models boasted a 5.4-liter Chrysler V8, later replaced by a quieter 5.9-liter Cadillac V8, propelling the Gladiator to 200 km/h and enabling it to sprint from 0 to 100 km/h in just eight seconds—outpacing the Cadillac Eldorado.

The interior features wood and round gauges.

The car featured a GM Hydra-Matic automatic transmission and power steering activated at the push of a button. Another button allowed the roof to retract, operated by a single electric motor—a stark contrast to the Ford Skyliner, which used seven motors for the same function.

Two “G” letters on the steering wheel hub.

The tachometer needle is designed like a sword, the brand’s symbol.

Debuting successfully at the 1955 Paris Auto Show, the Gladiator was a hit, and production of 25 units was planned. Intriguingly, the manufacturing was entrusted to Luftschiffbau Zeppelin—the airship makers!

The roof retracted into the opening trunk at the push of a button.

However, transitioning from airships to cars proved challenging, and quality issues led to a lawsuit, halting production. Initially priced at ten thousand dollars, the Gladiator’s cost eventually soared to 17.5 thousand dollars. Today, that would equate to around 200 thousand dollars.

Rear view: ribbed metal and fins.

Only three or four Gladiators were ever built. One resides in the Zeppelin Museum, another in a private U.S. collection, and a mysterious fourth is rumored to have vanished in Europe.

Today, the Zeppelin legacy extends beyond airships. The company now owns the renowned Caterpillar brand of construction machinery and engines. While they still manufacture airships, these are on a much smaller scale. A two-hour flight over Lake Constance on one of these modern airships costs 850 euros—a premium experience for the modern adventurer.

In the museum hall—the Gaylord Gladiator, its chassis…

…and a Zeppelin forklift, which was produced until 1995.

Photo: Zeppelin Company | Fedor Lapshin

This is a translation. You can read an original article here: Цеппелины: дирижабли и автомобили

Published May 16, 2024 • 8m to read