“Look to the root!” This was the advice of the unforgettable Kozma Prutkov in the century before last. Indeed, returning to the origins occasionally reveals fascinating discoveries. For instance, at the foundation of the Cadillac automobile brand surprisingly stands a Ford vehicle.

When you place the Ford Model A and the Cadillac Model A side by side, they are nearly indistinguishable at first glance. A closer inspection, however, reveals that while the Ford features fully elliptical suspensions at both the front and the rear, the Cadillac’s are semi-elliptical. The Ford Model A operates on two cylinders, compared to the single cylinder of the Cadillac Model A. Additionally, the Ford is slightly shorter, while the Cadillac is a bit wider. The Ford’s radiator is strictly vertical, contrasting with the Cadillac’s, which is slightly tilted back. The Ford also has a “well” for the essential crank handle of that era located on the right side, a feature absent on the Cadillac, where the shaft meant to be turned by the crank handle sits below the edge of the body. Clearly, these vehicles are structurally distinct, though visually similar.

The red color of the body is characteristic of the Ford Model A. The factory color of the first Cadillac Model A vehicles, according to the 1903 company catalog, was completely different: a rich cinnabar on the running gear (termed “red wine color”) and the same trim on a strict black body.

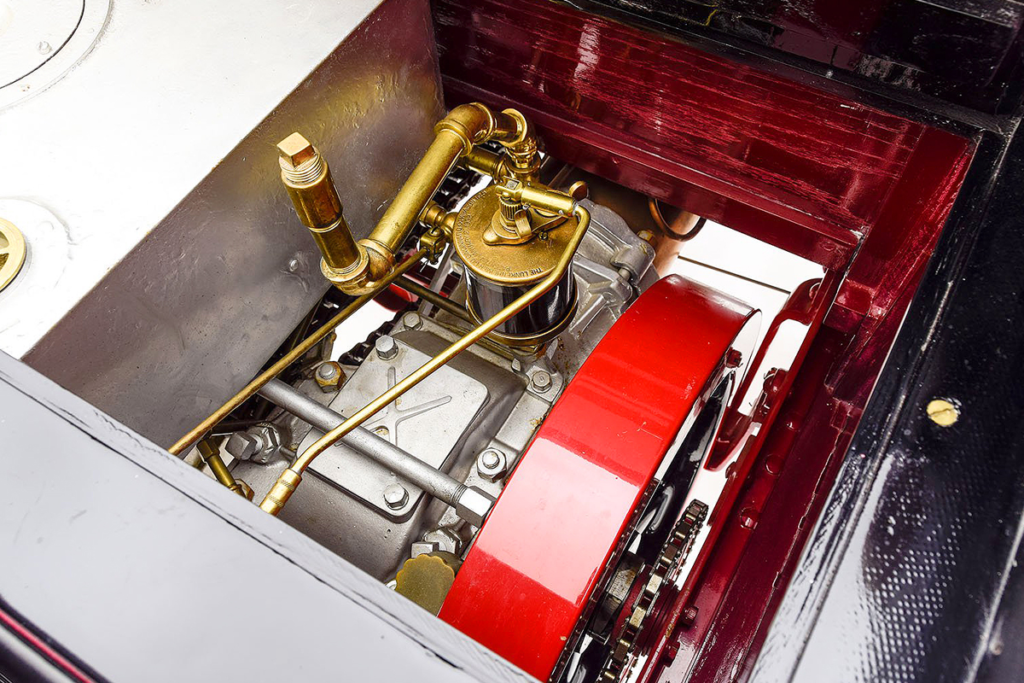

Here, it is clear where to insert the “crank handle” to start the engine: the starting shaft protrudes from under the side of the body next to the lateral lever axis. On Model A, the engine could be started from either side of the car; later, the “well” was only left on the opposite side.

The story unfolded on an August morning in 1902 when two gentlemen visited Leland & Faulconer in Detroit. They were representatives of the Detroit Automobile Company, a registered but non-operational firm, who had planned to market a vehicle designed by their chief engineer. Disagreements led to his departure, taking with him the prototype of the model intended for production. With nothing left to manufacture, the only option seemed to be to exit the business by selling the company. First, however, they needed to evaluate all available assets to determine the potential sale value. Leland & Faulconer, known for their sophisticated technical products and skilled staff, were asked to provide the necessary technical assessment.

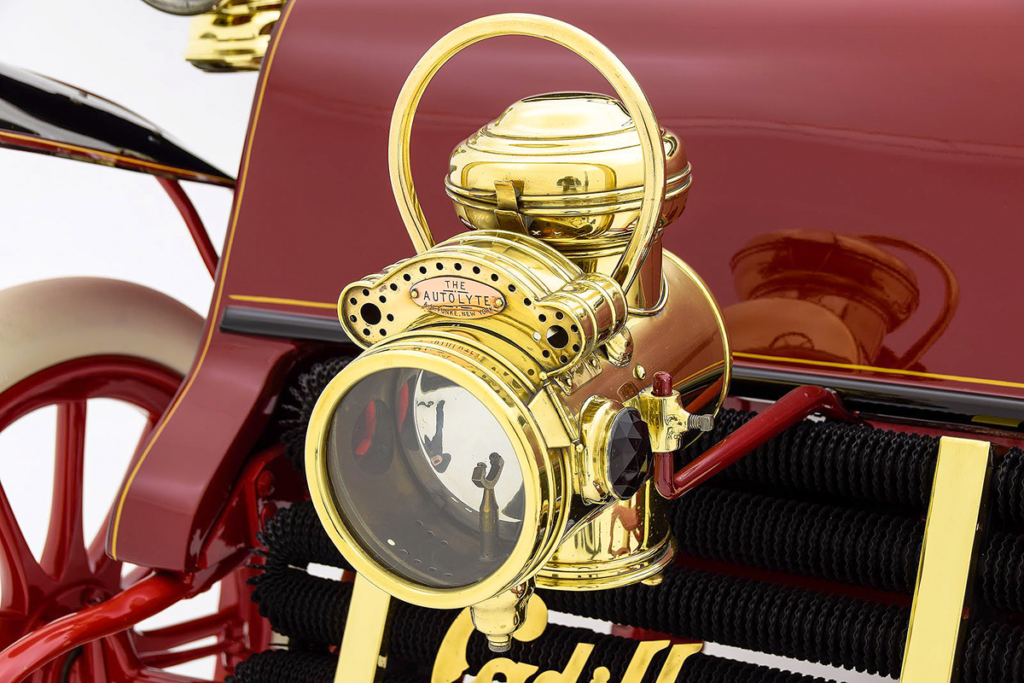

The powerful and bright front headlight is structurally combined with the carbide generator; it can be easily lit without being removed from its mountings—just open the front glass, which is hinged. The radiator of the car is a seamless copper tube with a diameter of five-eighths of an inch (15.9 mm), onto which copper discs are spaced at intervals of 9.5 mm. All this is coiled into a helix and mounted on the front with a slight backward tilt.

At that time, it would have been a stretch to call Leland & Faulconer an automotive company; they were a general metalworking firm known for supplying various production equipment and specialized tools such as micrometers to local businesses. Nonetheless, any product from this company was recognized for its supreme quality. Henry Leland, one of its founders and originally a gunsmith who started with Colt, ensured that all work in his shop was organized so that every component, especially the moving parts, were precisely fitted together without the need for additional finishing or filing. Their expertise in creating gearboxes, gear drives, and gear grinding setups was unmatched, and their foundry, established in 1896, was renowned across the region for producing castings of unparalleled quality.

The car shown here has neither instruments nor even a horn. Behind the doors in the front wall of the body, there is a water reservoir for the cooling system.

Bicycle manufacturers were eager to source gear wheels from them for chain drives. When Detroit decided to initiate a tram system, L & F was awarded the contract for the steam engines for the rolling stock, producing several hundred units. They also manufactured internal combustion engines, primarily for maritime use, commissioned by the local shipyard. When Ransom Olds, a budding entrepreneur from nearby Lansing, started his automotive venture, he placed his first order for two thousand single-cylinder engines with L & F.

The steering lever, moving along a toothed sector, sets the position of the throttle valve—in other words, it functions as an accelerator (“manual gas”). The right pedal is the brake, the left engages “low speed” of the two-stage planetary transmission. The lever to the right of the driver’s seat is loudly named “control handle” in the manual; in reality, it allows the driver to tighten the braking bands in the transmission at will, thereby enabling the car to move forward or backward.

Thus, representatives of the Detroit Automobile Company had every reason to consult with Henry Leland’s company. During his visit to assess the assets of the company being liquidated, Leland noted its well-equipped but dormant factory and a warehouse filled with unpainted bodies prepared in advance. He was impressed by the strategic setup of the equipment and inquired about the engineer whom the management could not accommodate. This was when Henry Ford’s name first emerged in this narrative, a figure with whom Leland would later develop a close and extensive collaboration. Ford’s former partners explained to Leland, “He was constantly driven by the desire to create high-speed racing machines, but we needed a model that could be quickly brought to market to generate revenue.”

The rear seats are cramped, with passengers having to sit at an angle to each other. If desired, the entire rear part of the body can be easily detached and removed from the car by four hands, making it a two-seater. Judging by the absence of attachments for a folding top, this car was originally delivered completely open.

A few days later, Henry Leland returned to the Detroit Automobile Company office at the corner of Cass Avenue and Amsterdam Avenue in Detroit. Without preamble, he told the partners, “I’ve brought your estimate, but I advise against selling this plant. Automotive manufacturing holds promise, though it comes with its challenges. Let’s rather continue designing the chassis from where you left off, and I will supply you with engines assembled with transmissions, as I have a suitable design ready.”

The car in these illustrations is shown in a four-seater version—this type of body was called a tonneau (French for “barrel”), and access to the rear seats was not from the sidewalk but from the road, through a single door. In this configuration, the car cost $850; a two-seater variant without a second row of seats was a hundred dollars cheaper.

Indeed, Leland had a suitable engine—it had been there since Leland & Faulconer worked under contract with Oldsmobile. Forced to outsource following a fire that destroyed their Detroit plant in March 1901, Oldsmobile hurriedly built a new factory in Lansing and set up temporary assembly operations to remain in the market. Leland & Faulconer were commissioned to produce a slightly improved version of the initial engine. Upon accepting this design for production, Mr. Leland tasked his engineers to further enhance it. Their efforts tripled the output to over ten horsepower at 900 rpm. The enhanced engine was duly offered to Olds as a replacement for the version already supplied. At that time, the offer was declined, citing the chassis was too weak for such an engine and the difficulties of the recovery period. Now, another opportunity to utilize the improved design presented itself.

Lighting devices were not included in the car’s delivery set; they had to be purchased separately. The kerosene lanterns on this specimen were made by the Dietz Motor Lamp company, and the acetylene headlamp was supplied by A.H.Funke of New York. The fenders, also known as mudguards, were still metallic here; they were sometimes made from artificial leather later on. The long and beautifully curved brackets of the front suspension, far extended forward, were one of the weakest points of the Cadillac Model A. They were not a unified whole with the frame but were attached to it with rivets and often could not withstand the loads on the extremely poor roads of that era. So from the following model year, they used a single transverse leaf spring instead of two longitudinal leaf springs—and inverted it.

The businessmen from Detroit Automobile Company lacked a frail chassis—in fact, they had no chassis at all, as their former chief designer had taken the prototype with him. Thus, nothing prevented them from designing the chassis from scratch to accommodate a more powerful engine. They didn’t have to contend with the aftermath of a fire either, so they unconditionally accepted the business model proposed by Henry Leland. By the end of August, all relevant documents were formalized and signed. It was not a merger or acquisition, and Leland & Faulconer remained an independent supplier of assemblies. However, Detroit Automobile Company had to be re-registered under a new name. Detroit had just celebrated its bicentennial, an event still fresh in everyone’s minds, and unsurprisingly, the name chosen for the reorganized company and the brand for the new car was that of the French explorer who founded the city. His name, Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, resonated powerfully and distinctly French—Cadillac.

To access the engine, you’ll need to remove the front seat cushion. The shiny rectangular box on the left is the fuel tank, and the brightly painted red cover is the planetary transmission casing.

Cadillac, or more precisely in French, “Cadillac,” is a geographical term long associated with a small settlement in the French Gironde region in Aquitaine. It’s unclear what connection the brave Gascon Antoine had with those places, having established the first trading post for furs with local Native American tribes where now stands a bustling multi-million city. Yet, it was his name and his family’s excessively pompous coat of arms that were chosen as symbols for the new automobile. The colorful and ornate heraldic emblem was applied to both sides of the car bodies by decalcomania on the very first production models, although its official registration as a corporate symbol was only formalized in August 1906.

From behind, a wonderful view of its chain main drive, the Brown & Lipe differential system, and the Atwood Castle kerosene tail light opened up. The wheels of the so-called artillery type on Cadillac production cars had 12 spokes. The first three units, including the prototype, used similar wheels with fourteen wooden spokes—from the Curved Dash Olds car. Pneumatic tires were supplied by Fisk and Hartford; here, of course, we see a modern imitation, but of the correct size 28 x 3 inches.

By the end of 1902, three cars had been assembled; they were showcased at the New York Auto Show in January 1903, where pre-orders were taken right at the exhibition stand for a modest ten-dollar deposit. In total, 2,286orders were collected by the end of the show; the factory commenced operations in March 1903, and sales began simultaneously. Henry Ford, on his part, only reached the market by the end of July. He could boast all he liked about his two cylinders in one engine, but he couldn’t hide the undeniable fact that he only managed to extract a mere eight horsepower from them. It’s no surprise that Cadillac significantly outperformed him in sales volumes, at least initially.

Both brands, Cadillac and Ford, have survived to the present day. They no longer compete directly, as Ford caters to the mass market segment while Cadillac remains a symbol of luxury and exclusivity, known as the “Standard of the World.” There’s little left for them to divide.

Photo: Sean Dagen, Hyman Ltd.

This is the translation. You can read the original article here: Самый первый Cadillac в рассказе Андрея Хрисанфова

Published August 01, 2024 • 9m to read