On paper, we have the results of measurements taken with precision instruments; on the computer screen, we have frames from a video shoot. As I examine them, I can’t help but feel relieved that I was on the motorcycle, positioned about three meters behind the car. We’re about to settle the debate over whose braking distance is shorter: a car’s or a motorcycle’s. For those who conclude their encounter with the results of our unique experiment at the Dmitrov test track with this, let me emphasize the most crucial point: in emergency braking situations, cars almost always come to a stop more quickly! And this insight is not just relevant for motorcyclists (at least, the sensible ones), but also for car drivers.

The misconception that motorcycles should decelerate as effectively as they accelerate (especially on dry, smooth surfaces) likely stems from their impressive acceleration dynamics. Even a seemingly modest BMW G 310 R, with its unassuming 34-horsepower single-cylinder engine, can hit the century mark in a mere seven seconds! So, one might expect motorcycles to brake just as impressively, right?

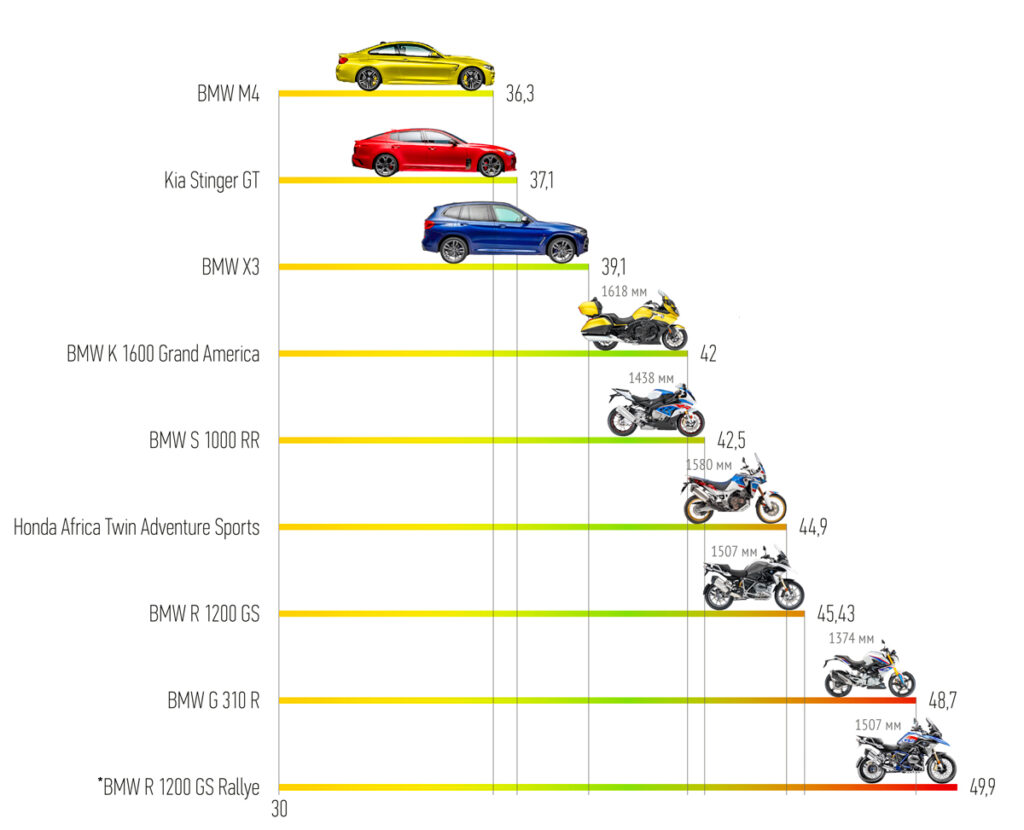

Now, about the test track. Representing the four-wheeled contingent were the BMW M4, Kia Stinger GT, and BMW X3. On the two-wheel side, we had a diverse lineup, ranging from the substantial touring cruiser BMW K 1600 Grand America to the unassuming roadster BMW G 310 R. In the middle, there were three adventure touring bikes (Honda Africa Twin Adventure Sports, BMW R 1200 GS, and BMW R 1200 GS Rallye), along with the sportbike BMW S 1000 RR. If we factor in the BMW GS Rallye, which was equipped with off-road tires, our selection of different motorcycle types was indeed quite comprehensive.

We intentionally selected roads that were not perfectly smooth, similar to what one encounters in everyday riding. Tire pressures were set according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. During braking, we simulated a panic press of the brake pedal (front brake lever and rear brake pedal for motorcycles) until the ABS engaged and brought us to a full stop.

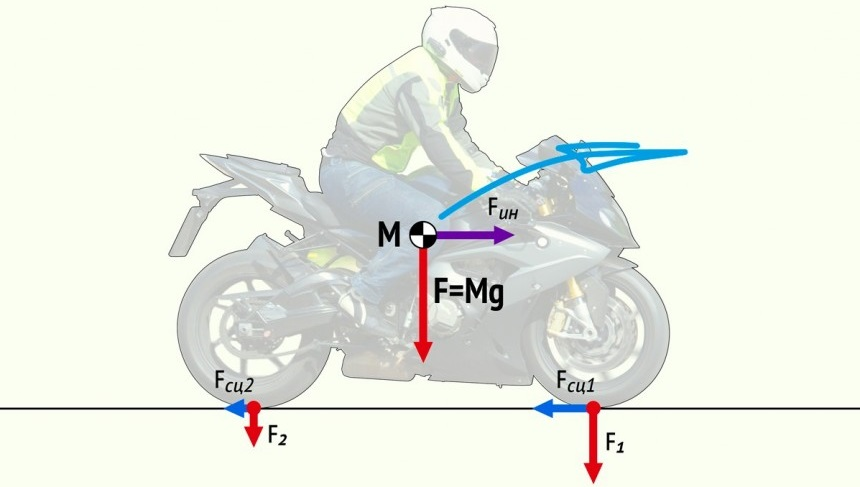

The effectiveness of motorcycle braking is influenced by a multitude of factors. It begins with the grip characteristics of the tires and their construction and extends to forces, moments of inertia, changes in fork compression during deceleration, the rider’s positioning and movements, brake system design, and the presence of ABS, among other advanced assist systems. However, our chief editor, who is passionate about motorcycles yet unapologetically meticulous, would insist on a discussion of concepts like “low braking force” or, worse still, “the wider the tire, the larger the contact patch.” He would promptly produce a sheet of paper, covered with vectors both lengthwise and crosswise, and engage in a relentless pursuit of a well-reasoned agreement regarding the magnitude of the frictional force in the tire’s contact patch with the road.

To put it succinctly, the longer the wheelbase and the lower the center of gravity, the shorter the braking distance. This results in fewer undesirable side effects during intense deceleration, such as stoppies or tail wiggles, which shorter-wheelbase sportbikes and nakeds are particularly susceptible to. Beyond this, there are nuances that are worth exploring.

Professional racers employ a concept known as “compressing the suspension” to maximize traction with the surface. Racers from various racing series “flatten” the front fork and monoshock to load both wheels, thereby increasing their contact patch. While linear relationships define many aspects (the frictional force in the contact patch is the product of the coefficient of friction by the weight resting on the wheel), in the context of braking, a larger contact patch is indeed an advantage. However, long before the front tire loses grip, most short-wheelbase motorcycles start lifting the rear wheel into the air. To delay this occurrence, racers lean as far back as possible during braking, shifting the center of gravity toward the rear wheel. Nevertheless, these strategies are prevalent in professional racing on closed tracks, where fractions of a second make all the difference. But what happens on regular roads?

All four-wheeled vehicles, when rapidly decelerating from a speed of 100 km/h, predictably produced a range of results, spanning from 36.3 meters (BMW M4) to 39.1 meters (BMW X3). Naturally, we didn’t disable the ABS, especially since motorcycles have long been equipped with anti-lock braking systems. In fact, ABS has been mandatory for all new motorcycles with engines larger than 125 cc sold in Europe since 2015. Incidentally, BMW was among the pioneers, introducing the BMW K 100, a production model with ABS, back in 1987!

However, even experienced riders, as seen in premier-class MotoGP races, can make the critical mistake of locking the front wheel – a scenario that guarantees disaster, ranging from a relatively gentle slide to the ground to, in unfortunate circumstances, the rider being launched into the sky. It’s important to note that riders with ABS can also experience front-wheel lockups. If ABS were permitted in races, it’s safe to say that the desire for spectacle from the crowd and the profit-seeking motives of event organizers and broadcasters would likely lead to more crashes.

By the way, locking up the rear wheel is also highly undesirable. Although it doesn’t always result in a crash, the fishtailing rear end of a motorcycle is far from being a friend to stability and reduced braking distances.

Now, let’s shift our focus to motorcycles. I’ll begin with the top performer in our lineup: the hefty (364 kg fully loaded) BMW K 1600 Grand America came to a stop in the shortest distance – just 42 meters. Remarkably, it didn’t require any compensatory or defensive maneuvers on my part. It’s nearly impossible to induce this two-wheeled limousine into a stoppie, and we can credit the longest (1618 mm) wheelbase among our test subjects for that. Furthermore, BMW’s trump card here is the Duolever front suspension on the “Big America.” The standout feature of this quasi-automotive design is that, no matter how hard you brake, the tendency for the front wheel to lift remains minimal. In other words, during deceleration, there’s no jolting or instability – the motorcycle remains resolutely stable.

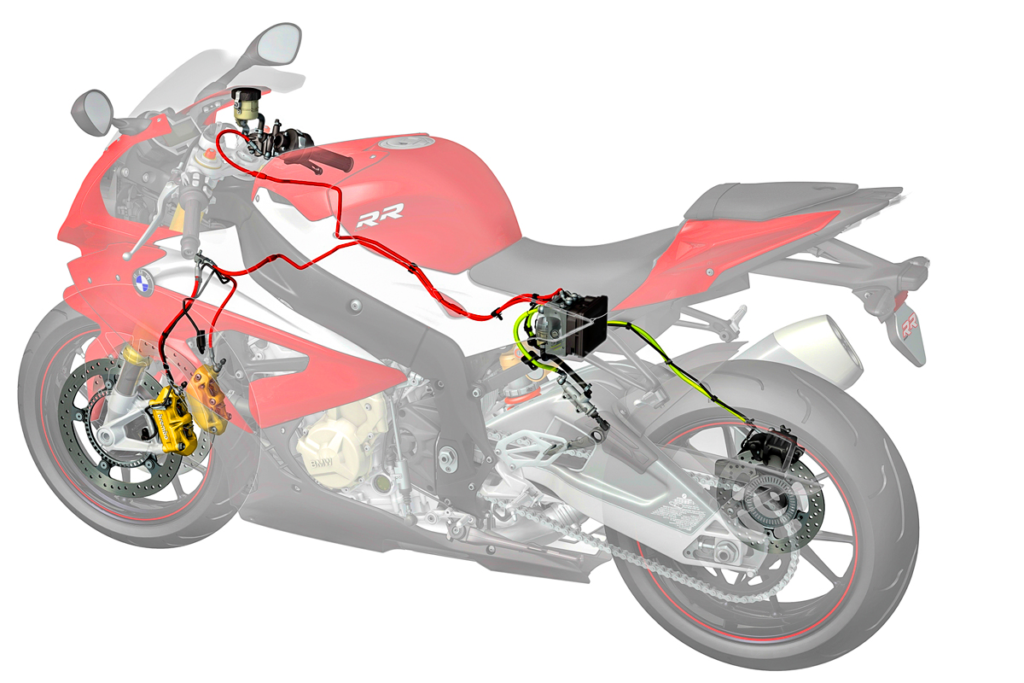

Next on our list of “brake performers” is the BMW S 1000 RR sportbike, with a braking distance of 42.5 meters, despite being loaded with electronics akin to a high-tech apple with all the bells and whistles. It boasts Dynamic Damping Control (DDC), Automatic Stability Control (ASC), Dynamic Traction Control (DTC), and Bosch’s intelligent brake-pad-wearing sensor, all integrated with a linked braking system. This system initiates partial rear brake application when the front brake lever is pressed. It’s worth noting that the same brake system is installed on all “big” BMWs in our test, including the BMW K 1600 GA and the two “geese,” respectively.

Returning to our discussion about motorcycles, one undeniable truth remains unassailable: the shorter the wheelbase, the more precarious the motorcycle becomes during intense braking – and the more apparent its tendency to tip over.

The Honda Africa Twin Adventure Sports, equipped with a standard two-channel ABS, exceptionally long suspension travel, front and rear brake calipers relying solely on the rider’s inputs, and a front wheel with a 21-inch diameter – almost reminiscent of a bicycle wheel – held its ground admirably. Surprisingly, despite these characteristics, it outperformed its classmate, the BMW R 1200 GS, which features a 19-inch front wheel with a 120mm profile width. It’s worth recalling that, according to formal formulas, the contact patch area isn’t directly influenced by width; instead, it alters the shape and orientation of the contact patch, potentially redistributing loads within it while maintaining the same overall area. As for the “goose,” it’s noteworthy that despite its electronics-laden configuration similar to its sportbike counterpart, it still required 45.4 meters to come to a complete stop.

But, as the saying goes, you get what you pay for. Honda’s Africa Twin Adventure Sports lifted the rear wheel into the air during braking, whereas the BMW R 1200 GS remained steadfast and stable, courtesy of its signature Telelever front wheel suspension. Intriguingly, the budget-friendly BMW G 310 R, equipped with a single brake disc (albeit with a substantial diameter of 300 mm) and a four-piston radial caliper by Bybre (a licensed Brembo product), managed to halt from 100 km/h almost like a freight train, covering a substantial distance of 48.7 meters. However, it’s important to note that, as per Podorozhansky’s calculations, mass doesn’t significantly affect the equation describing maximum deceleration. This “Indo-European” model, assembled at the TVS factory in India, exhibited decent behavior with its straightforward two-channel ABS. It didn’t attempt to lose control, but a closer look at the result reveals…

Moving on, we come to the “big goose” – the BMW R 1200 GS Rallye, shod with relatively “aggressive” off-road Michelin Anakee Wild tires, which needed 49.9 meters to come to a halt. The explanation for this lies in the peculiarities of off-road tire tread performance on asphalt. However, this comes with an unwelcome side effect: during cornering, the motorcycle exhibits wobbling, and these wobbles manifest even on leans that would be inconsequential for road tires. This is the price one pays for the ability to conquer off-road terrain and a significant reason to adjust your riding style when on asphalt. It’s crucial to remember that all of these commendable braking distances were prepared under controlled conditions, and in a real emergency, you should add another five, or even ten meters to these distances.

Braking distances

* off-road tires

Now, let’s delve into a crucial aspect of ABS. If this system does indeed help reduce braking distances, it’s primarily because it enhances stability during deceleration, thereby reducing the chances that the braking process (and, heaven forbid, a life-threatening situation) relies solely on the tires rather than other components of the motorcycle’s design and the rider’s skills. Moreover, on rough road surfaces, ABS can sometimes lead to an increase in braking distance.

But, could I, as a motorcycle rider, outperform the braking capabilities of at least the BMW X3 crossover? The possibility exists, although it’s a largely hypothetical scenario. To achieve this, we would need impeccable asphalt conditions, the longest wheelbase among our test subjects – the BMW K 1600 Grand America, and racing slicks warmed up to optimal operating temperatures, all with ABS turned off. Even then, any improvement in braking would likely be marginal. Furthermore, envisioning such a scenario in the daily life of a cruiser owner seems far-fetched. In our experiment, we measured the braking distance of the BMW S 1000 RR from 200 km/h. The “German” sportbike merrily bounced on irregularities, attempting to defy gravity, swaying its rear end, and nearly achieving escape velocity – coming to a halt after a daunting 177 meters!

As for motorcycles with shorter wheelbases that tend to perform stoppies, our meticulous chief editor insists that the likelihood of achieving car-like braking intensity increases as the coefficient of friction decreases. I’d like to add that this remains unlikely due to the new obstacles that slippery roads introduce, often thwarting any attempts at intense braking.

But can you outperform ABS on a motorcycle? The answer is yes, but it comes with significant caveats. I’ve successfully executed this feat on racetracks multiple times. However, it requires ideal conditions such as warmed-up racing slicks, pristine asphalt, and predefined points on the track where I initiated braking. Moreover, I didn’t bring the motorcycle to a complete stop but merely reduced speed before entering a turn. These conditions are a far cry from real-world riding. Thus, on my KTM 990 SMT, where ABS can be conveniently disabled with a single button press, I typically keep it activated. What if it’s raining, the road surface is uneven, or other road users make unexpected maneuvers? In all these scenarios, ABS will outperform the braking skills of 99.9% of motorcyclists, regardless of their level of experience.

Now, let’s consider a scenario where a motorcycle lacks ABS altogether. In such cases, it’s advisable to “dip” the rear suspension by applying the rear brake while simultaneously and smoothly engaging the front brake lever, ensuring that the front wheel hovers on the edge of locking. Interestingly, this advice holds true even for motorcycles equipped with ABS. However, owners of advanced motorcycles with combined braking systems can exclusively manipulate the front brake lever, with the electronic control systems taking charge of the rest. In the future, these electronic systems may not only determine how to apply the brakes but also make decisions about our riding trajectory. Until that future arrives, the choice of whether to buy a motorcycle with ABS or without one boils down to a simple question: Do I have the good fortune and the physical health to afford a motorcycle without ABS?

| Car/Motorcycle | Tires | Size |

| BMW M4 | Michelin Pilot Super Sport | 255/35 R19, 275/35 R19 |

| Kia Stinger GT | Continental SportContact 6 | 225/40 R19, 255/35 R19 |

| BMW X3 | Pirelli Cinturato P7 | 245/50 R19 |

| BMW K 1600 Grand America | Bridgestone Battlax BT-022 | 120/70 R17, 190/55 R17 |

| BMW S 1000 RR | Pirelli Diablo Superсorsa | 120/70 R17, 190/55 R17 |

| Honda Africa Twin Adventure Sports | Dunlop Trailmax D610 | 90/90 R21, 150/70 R18 |

| BMW R 1200 GS | Michelin Anakee | 120/70 R19, 170/60 R17 |

| BMW G 310 R | Michelin Pilot Street Radial | 110/7 0 R17, 150/60 R17 |

| BMW R 1200 GS Rallye | Michelin Anakee Wild | 120/70 R19, 170/60 R17 |

Two-Wheeler ABS Nuances

Two-channel ABS relies on data from sensors measuring the angular speed of the front and rear wheels. When it detects a difference (indicating the possibility of one wheel locking up), it modulates the pressure in the corresponding brake circuit by reducing and then increasing it. However, there’s a fundamental difference between cars and motorcycles. Cars, if they lean at all, do so only mildly, and often in the opposite direction of the turn’s center. Motorcycles, on the other hand, always lean while turning. In 2014, Austrian manufacturer KTM, in partnership with Bosch, introduced what’s known as “Cornering ABS” on the KTM 1190 Adventure, becoming a pioneer in this technology. The folks at BMW followed suit in 2015, naming their version “ABS Pro” (with Bosch’s involvement, of course). These systems go beyond wheel speed sensors, incorporating an inclination sensor. They not only identify the lean angle but also analyze data on longitudinal and lateral accelerations, throttle position, selected gear, engine mode, and more. Based on this data, they decide how to distribute the workload between the front and rear brakes in the combined brake system. Bosch claims that these decisions are made a staggering 100 times per second.

Continuing on, let’s explore what this feels like in real-world practice. When I take my KTM 990 SMT out onto the track, I often find that regular ABS tends to intervene too aggressively during turns. It releases the brakes well before reaching genuinely critical moments, albeit with some involuntary trajectory straightening. However, when it comes to the intervention of “cornering” ABS on the BMW S 1000 RR or KTM 1190, it’s a nearly imperceptible experience. Yet, it works wonders by allowing me to extend my braking points without increasing the turn radius. Even during the most active phase of braking, I still maintain precise control over the motorcycle, enabling me to change its trajectory and perform maneuvers I never dreamt of before.

The Right Finger Grip

Now, let’s dive into one of the most debated topics among motorcyclists: how many fingers should you use on the brake lever – one, two, or maybe all four? The answer is straightforward: employ as many fingers as necessary for effective deceleration of your specific motorcycle while ensuring you maintain complete control over the handlebar grip.

Author: Vladimir Zdorov

Photo: Nikita Kolobanov

This is a translation. You can read an original article here: Точка невозврата: разбираемся в тонкостях торможения на мотоцикле и на автомобиле

Published September 20, 2023 • 13m to read