The Raba diesel chuffs out Euro-0 exhaust, and I once again feel like a student taking my bus driver’s test on the training ground. I’m slowly driving around the bus depot, making a reverse turn, feeling for the gears with the long shift lever, and carefully guiding the Ikarus through the doors of the paint shop for a respray.

Before this, I had only driven an intercity Ikarus once, back in 2001. At that time, all over the country, Ikaruses were being fitted with domestic engines to replace the original Hungarian ones, which were worn to the limit: some were adapting YaMZ diesels from MAZ and KrAZ trucks, while others even tried installing tank engines from Barnaul… But a firm from Naberezhnye Chelny called Kora installed a Kamaz powertrain, taking advantage of the KAMAZ plant being right next door. To make the bulky V8 diesel fit in the engine bay, they had to cut the frame and build a large housing that intruded into the passenger cabin, and the gearshift was terrible: I could barely find the gears. But when you’re desperate, even a bus like this will do.

This Ikarus has a clearly better gearshift, although the “poker” lever and the long linkage rods running to the rear are quite a combination. The shift pattern is roughly like that of the LAZ-695N—”reversed”: first gear is to the right and back, second is straight forward, and so on.

The engine, like other components, is original: a 140-horsepower horizontal Raba-MAN ‘six’ sits in the rear. Most importantly, the original interior has been preserved, even though this particular example was built back in 1977. It’s simply a time capsule—or rather, an Ikapsula! But how does a bus that’s nearly half a century old survive in such a state? The fact is, for a significant part of its life, it literally never left the garage. The story goes that a certain Soviet minister arrived with his entourage in Murmansk, and they provided him with a PAZ minibus. The minister was furious, so for his subsequent visits, this Ikarus was brought in—reportedly taken straight from the exhibition at Moscow’s VDNKh. The bus’s exhibition origins are hinted at by the unusual light-beige seat upholstery and the Ikarus logo embossed on the steering wheel, a rare feature.

The interior with light beige leatherette upholstery is in excellent condition

The interior with light beige leatherette upholstery is in excellent condition

Seat numbers, similar to cloakroom numbers, are nailed to the backs with nails

Later, the bus worked in the Murmansk port, ferrying power plant employees, and has now made it to St. Petersburg under its own power without a single breakdown.

The collection of the St. Petersburg retro-bus mafia already includes a dozen tourist Ikaruses from the 200-series. I photographed two of them on the grounds of the “Center of Leningrad Automotive History” museum. One, a 12-meter Ikarus-250, is a true “heavy luxury” model. It bears Sovtransavto logos below the windows, homemade flip-down plexiglass headlight covers (fitted not just for looks but to protect the imported lenses from stones), and a charming external thermometer on the A-pillar. Next to it stands a shorter, 11-meter Ikarus-256.

Thermometer screwed to the windshield seal

On the museum site — Ikarus-250 (1969-1996) and Ikarus-256 (1977-2002)

But the grille of the subject of this article bears the index 260. Weren’t Ikarus-260 models for city use? It’s simple: what we have here is an Ikarus-255 (to be precise, a 255.70); someone in the past replaced its lost badge with another. This model is also 11 meters long, like the later Ikarus-256, but it has leaf springs instead of air suspension.

The main feature of the 255 model is the leaf spring suspension (visible in the background)

Instead of the “260” badge there should be “255”

It’s clear that leaf-sprung Ikaruses were less comfortable, so they were typically used on short intercity routes or in cities—for transporting foreign tourists and airline passengers. However, they were valued for their indestructibility: the leaf springs might sag from a hard life but would keep working, whereas airbags could deflate completely! The ‘255’ was slightly less speedy than the ‘250’ (top speed 100 km/h vs. 106 km/h) but more fuel-thirsty (official fuel consumption 28.5 l/100km vs. 26.5 l/100km). From 1969 to 1982, a total of 24,196 Ikarus-255 buses were built, 16,219 of which went to the USSR.

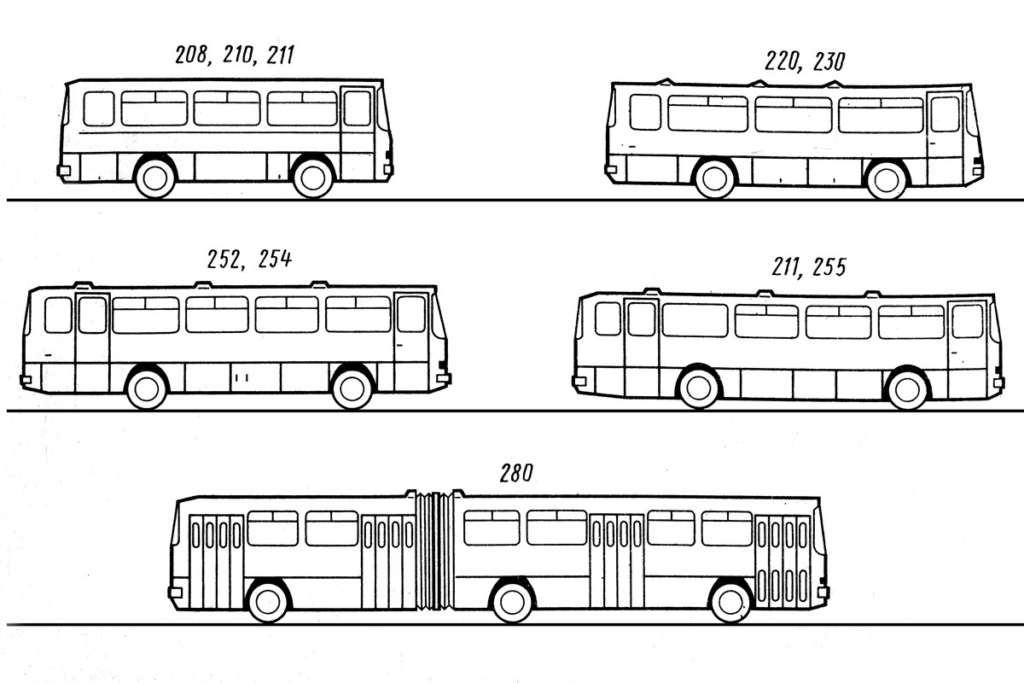

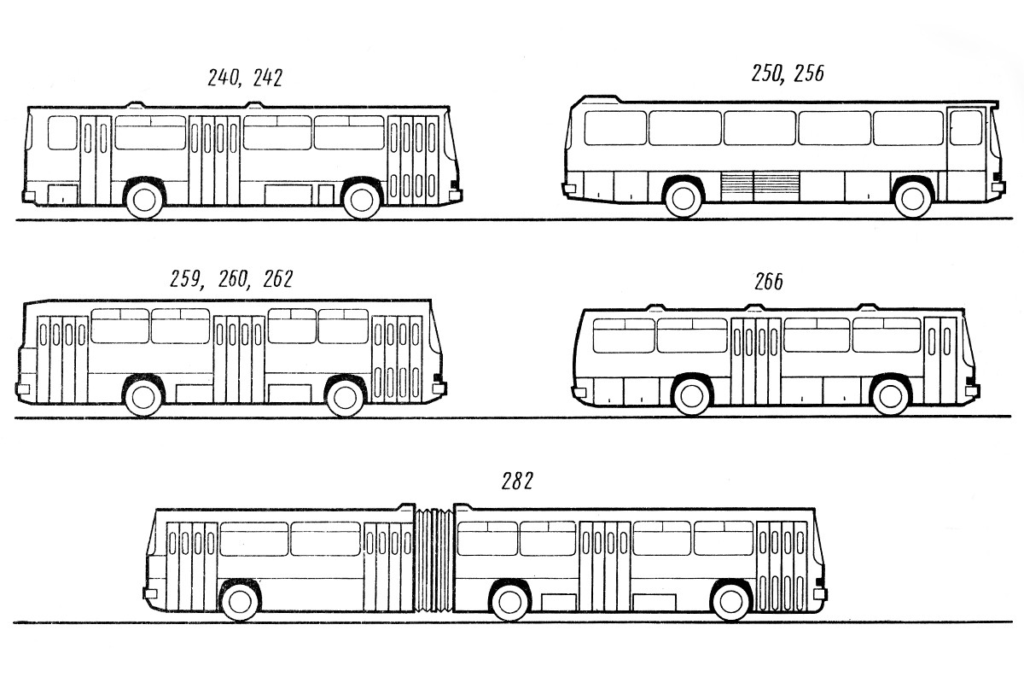

Ikarus buses of the two hundredth series

Of course, nearly fifty years is a long time even for such a well-preserved machine. The paint is flaking in places (the bus has been repainted three times, ending up in a non-standard livery), there are some rust streaks visible, the engine cover is jammed shut, and the rear axle has shifted slightly from its position. But the interior trim, I repeat, is almost all there (it has 45 passenger seats), with net luggage racks under the ceiling.

Here and there you can see streaks of rust

Here and there you can see streaks of rust

The bus was repainted three times

Opposite the doors are folding seats: a two-seater at the rear and a single seat for a guide at the front. On the dashboard is a plaque that reads “Mogurt, Hungarian Foreign Trade Enterprise for Motor Vehicles.” Bard Yuri Vizbor sang: “To Shchyolkovskaya I take the metro, from Shchyolkovskaya—a bus, and in my string bag six kilos of Globus vegetable conserves…” Green peas from Globus were also imported from Hungary.

Sign on the front panel

Next to the driver is a folding seat for the guide

Opposite the rear entrance are two folding passenger seats (one missing)

The driver faces a woodgrain-finished dashboard, a powerful heater under the seat, massive floor-mounted pedals, and large instrument dials. In the middle of the cluster on the left is a bright red warning light: it illuminates if the engine oil pressure or air pressure in the brake circuits is too low. On the same dial is another red warning light for alternator load. If it glowed dimly, the charging system had failed, but if it was blazing, the current limiter had been triggered. Then you had to shut off the engine and toggle the master switch—in simpler terms, reboot the system. If that didn’t help, you had to clean the battery terminals.

The driver has a wood-look panel, floor pedals and a large gearshift lever

From left to right: tachometer, instrument cluster, two pressure gauges, tachograph

Floor pedals

Heater under the seat

The engine is started by turning the starter handle next to the ignition key. And do you know where the handbrake is? Between the seat and the left side panel: I didn’t find it at first!

By the time this article was prepared for publication, the St. Petersburg Ikarus-255 had left the paint shop. It was repainted—sadly, losing its unique livery but returning to the classic “scarlet top, white bottom.”

Of course, tourist Ikaruses have been preserved in other parts of the country. Recently I spotted a seemingly intact model 256 near a cafe on the Kazan–Naberezhnye Chelny highway, which hosts a museum of Soviet artifacts and displays various retro vehicles. This 1987 specimen used to transport employees of the Kazan Elekon factory (the one that made model KAMAZ trucks and other vehicles), then stood on a city street for a long time. Now, judging by the gutted interior filled with stored tables and chairs, it seems they want to turn the Ikarus into a summer veranda.

This example transported employees of the Kazan Elekon plant

And one last thing. At the InnoTrans passenger transport exhibition recently held in Berlin, electric Ikarus buses were shown! Has the brand been revived? Yes, but in much the same way as Moskvich: we’ve already reported that the current Ikaruses are merely Chinese vehicles, assembled in small batches in a small workshop…

Perusing an Old Manual

Before you is a book published in 1987—”Operation and Repair of Ikarus Buses,” a translation from Hungarian. As stated, it was the first (and apparently only) publication of its kind in our country, because in the twenty years of Ikarus deliveries to the USSR, starting in 1967, no such reference literature had been published in Russian. Although, judging by the same book, the lion’s share of Ikarus’s production—10,000 out of 13,000 vehicles annually—was intended specifically for the Soviet Union.

The preface to the Russian edition has an interesting note: “Material on the Praga 2M.70 hydromechanical transmission (HMT) has been omitted, since buses supplied to the USSR are equipped with the Lviv-3 HMT, which has significant differences.” Furthermore, it states that “the factory has begun installing front axles of Soviet production, received under COMECON cooperation”: these were supplied by LiAZ.

Batteries are on a retractable platform behind the hatch at the stern

At that time, Ikaruses were very high-tech products for our country and required particular care during maintenance and repair. This applied to their diesels with precise fuel injection equipment (Soviet LAZ and LiAZ buses of those years were gasoline-powered), the air suspension, and the pneumatic system in general. For example, Ikaruses were fitted with fuel injection pumps from six different models—from Poland, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and West Germany. And during repairs, much had to be adapted to our reality: instead of the Rocol grease specified in the book, the use of Litol-24 was prescribed; instead of imported Molard paste and YVS oil, proletarian solidol was used. And it’s unlikely the USSR had the official Palmarapid glue for repairing the articulation bellows of “accordion” buses. Furthermore, as the book states, “there is currently no major overhaul for Ikarus buses in the USSR.” How that could be with such gigantic delivery volumes remains a mystery!

Photo: Fedor Lapshin

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: Икапсула времени: экспресс-ретротест автобуса Ikarus-255 с необычной судьбой

Published September 11, 2025 • 8m to read