A Swiss car might sound unconventional. Swiss banks, Swiss cheese, or Swiss watches, now those are familiar. Yet, a century ago, Switzerland was as much a car nation as many of its neighbors. Automotive manufacturers like Piccard-Pictet in Geneva, Turicum in Zurich, Berna in Bern, Saurer in Arbon, and Martini in the provincial Saint Blaise were bustling. Even the lesser-known Zedel nestled between Lausanne and French Besançon produced cars, often quite respectable ones.

However, this vibrant diversity vanished by the late 1930s. Only Saurer and Berna survived, strategically shifting from passenger cars to focus on trucks, buses, and later, trolleybuses. Luxurious Piccard-Pictet couldn’t withstand competition and shuttered in 1924. Martini, sold to the Steiger brothers the same year, lasted barely a decade. Zedel fell to the French company Donnet and ended its run in 1934. Turicum stopped producing cars in 1912 amidst financial woes, though it was listed as an automotive company until 1925. Smaller manufacturers like Dufaux, Egg, Ajax, and Tribelhorn disappeared before the 1920s.

Effectively, the Swiss automotive industry was decimated by World War I, with the Great Depression wiping out the few survivors; no passenger car manufacturers made it to the 1940s. Post-war, Switzerland had other priorities; it was simpler to import cars from neighboring automotive powerhouses than produce them locally. Hence, the rise of trade agencies selling foreign cars to meet every taste and budget.

The instrument dials have German lettering, but the speedometer is graduated in miles per hour rather than kilometers per hour

Our story begins in such an agency, not in capital Geneva or industrial Bern, but in the cosmopolitan, university city of Basel. This agency imported various high-end brands, where Mr. Monteverdi’s son, Peter, grew up. Unlike his peers, Peter had no interest in watchmaking or cheesemaking; he was set on following in his father’s footsteps.

Peter first dabbled with karts, which at the time were called “go-carts” and considered slightly more serious than racing soapboxes downhill. His father’s agency provided ample space for warranty repairs and regular maintenance, where Peter toyed with his “sports equipment.” By the early sixties, he built a more serious racing car compliant with “Formula Junior” technical regulations. Several were made, each bearing the initials MBM—Monteverdi Basel Motoren—crowned with a proud emblem. Although these cars competed in sports events, they achieved limited success. Peter’s single Grand Prix attempt in Germany in 1961 ended with an early retirement.

Basel is uniquely situated where Switzerland meets France and Germany, split by the Rhine. In the 14th century, it was divided into Greater and Lesser Basel. Residents of Lesser Basel, often harassed by their wealthier neighbors, still hold end-of-January carnivals, turning their backs—or more accurately, their rears—to Greater Basel in a defiant display of independence. These festivities, complete with elaborate costumes and symbols of medieval guilds, stretch throughout the day, punctuated by food and drink.

In this complex environment, Peter Monteverdi’s agency thrived in the Binningen area, drawing customers from both Basels and beyond. The agency sold a variety of high-end cars—BMW, Lancia, Bentley, and later, under Peter’s influence, became Switzerland’s first Ferrari importer. Over time, Peter recognized his clientele’s preference for high-speed vehicles suitable not just for sports but for cruising through Alpine passes and visiting Mediterranean resorts. This niche had recently been vacated by Facel-Vega of France under unfortunate circumstances.

Peter chose a tried-and-true formula used by Jensen, Railton, and Facel-Vega: combining a European chassis with an American engine, a strategy proven until Facel-Vega faltered after rejecting American engines. A deal was struck with Chrysler Corporation to supply power units and other components, while Italian designer Pietro Frua handled the bodywork, with final assembly set in Binningen. The resulting model, the Monteverdi High Speed 350S, was unveiled at the 1967 Frankfurt Auto Show, with sales starting gradually.

By 1968-1969, Frua’s atelier had delivered eleven fully finished bodies, all two-seaters. Dissatisfied with the craftsmanship, Peter switched suppliers to Fissore, which produced a revised “2+2” version named the High Speed 375L, the model featured here.

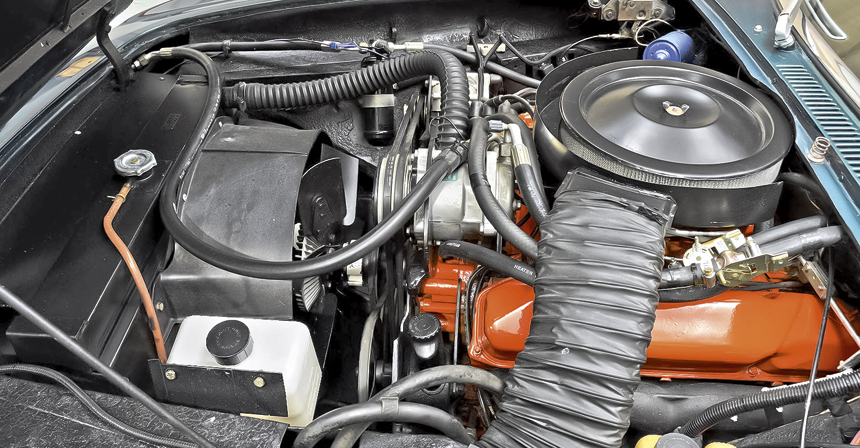

This model sports a distinct front end with four headlights and a more angular style yet retains its elegant proportions. The example shown, factory number 2020 from 1970, features the renowned Chrysler Magnum 440 engine with a 7.2-liter displacement, producing 375 horsepower. Over time, a version with 450 horsepower and options for a four-speed manual or a three-range automatic transmission (both from Chrysler) was offered; this particular car has the automatic TorqueFlite.

True to its GT-class luxury, the car is equipped with electric windows, air conditioning, power steering, and a later addition of a Kenwood stereo system with CD player—introduced long after the car’s manufacture.

Monteverdi aimed to produce about fifty cars annually. However, demand waned by 1976, and production of convertibles and four-door sedans ended sooner—only about thirty were made. The company shifted focus to producing SUVs based on Range Rover units (Monteverdi Sahara), utility vehicles (Monteverdi Safari), and later, sedans and convertibles under the Sierra designation, and in 1982, the Tiara—a slightly modified Mercedes-Benz. Following Peter Monteverdi’s death on July 4, 1998, after a lengthy illness, the Binningen enterprise closed for good.

Now, it houses a museum.

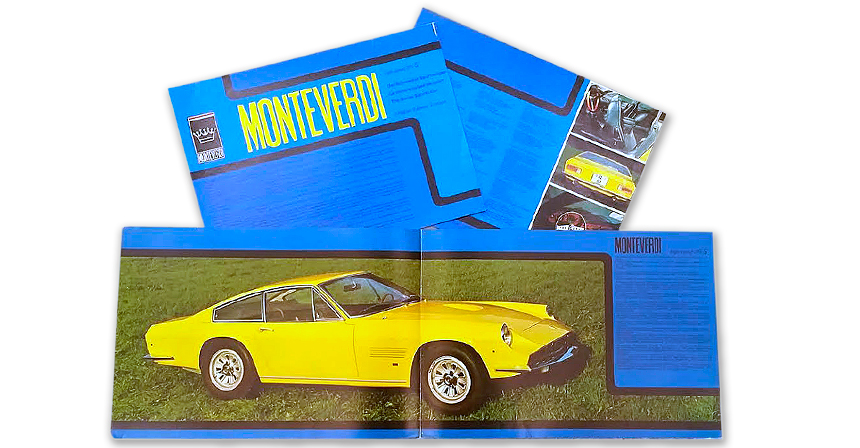

The illustration from the company brochure shows an early version of the car with a fundamentally different frontal solution

The author extends heartfelt thanks to Elena Lukyanova, a resident of Basel, for the historical and regional information used in this article.

Photo: Sean Dugan, www.hymanltd.com

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: Суперкар из Швейцарии: Monteverdi High Speed 375L 1970 года в рассказе Андрея Хрисанфова

Published October 17, 2024 • 8m to read