In order to understand how a semi-automatic transmission works, we will have to remember the design of a conventional manual transmission. The basis of a classic manual transmission is made up of two shafts — a primary (driving) and a secondary (driven). The torque from the engine is transmitted to the primary shaft through a clutch gear. The converted torque is transferred to drive wheels from the secondary shaft. Both the primary and secondary shafts are equipped with gears that are engaged in pairs. But on the primary, the gears are fixed rigidly, and on the secondary, they rotate freely. In the “neutral” position, all the secondary gears spin freely on the shaft, that is, the torque isn’t transmitted to the wheels.

Before shifting a car into gear, a driver presses a clutch, disconnecting the primary shaft from an engine. Then, by using a gearbox lever, special devices, synchronizers, are moved through the traction system on the secondary shaft. When connecting, the synchronizer clutch rigidly locks the secondary gear of the desired speed gear on the shaft. After the clutch engagement, the torque with a given coefficient begins to be transmitted to the secondary shaft, and from it to the main gear and wheels. To reduce the total length of the box, the secondary shaft is often divided into two, distributing the driven gears between them.

The principle of operation of semi-automatic gearboxes is absolutely the same. The only difference is that servo actuators are engaged in closing/opening the clutch and selecting gears. Most often, this is a stepper electric motor with a gearbox and a servo unit. But there are also hydraulic actuators.

An electronic unit controls the actuators. At the command to switch, the first servo depresses the clutch, the second moves the synchronizers, putting into the desired gear. Then the first one slowly releases the clutch. Thus, the clutch pedal is no longer needed in the cabin — when the command is received, the electronics will do everything by itself. In automatic mode, the command to change the gear comes from a computer that takes into account the speed, engine speed, data from ESP, ABS and other systems. And in manual mode, a driver gives the order to switch using a gearbox selector or paddle shifters.

The problem of the semi-automatic transmission is the lack of clutch feedback. A person feels the moment of the disks’ closing and can switch the speed quickly and smoothly. And the electronics has to be careful: to avoid jerks and keep the clutch, the semi-automatic transmission breaks the power flow from the engine to the wheels for a long time during the shift. Uncomfortable dips appear during acceleration. The only way to achieve comfort when switching is to reduce its time. And this, alas, means an increase in the price of the entire unit.

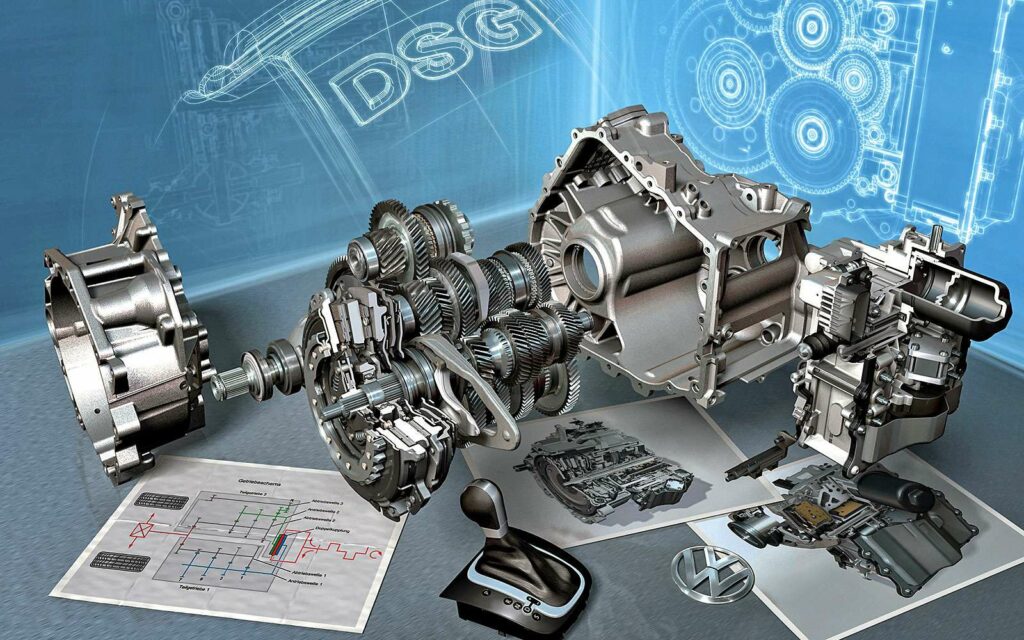

A DCT (dual clutch transmission) that appeared in the early 80s was a revolutionary solution. Let’s consider its work on the example of a 6-speed DSG box of the Volkswagen concern. The gearbox has two secondary shafts with driven gears and synchronizers located on them – like a six-speed Golf mechanical gearbox. The trick is that there are also two primary shafts: they are inserted into each other on the principle of a matryoshka doll. Each of the shafts is connected to the engine through a separate multi-disk clutch. The gears of the second, fourth and sixth gears are fixed on the external primary shaft, the first, third, fifth and reverse gears are fixed on the internal one. Let’s say a car starts accelerating from rest. The first gear is actual (the clutch blocks the driven gear of the first speed). The first clutch is closed, and the torque is transmitted to the wheels through the internal primary shaft. Let’s go! But simultaneously with the engagement of the first speed, smart electronics predicts the subsequent engagement of the second one – and blocks its secondary gear. That is why such boxes are also called preselective. Thus, two gears are actual at once, but there is no jamming – the drive gear of the second speed is located on the external shaft, the clutch of which is still open.

When the car accelerates enough and the computer decides to shift up, the first clutch opens and the second one closes at the same time. The torque now goes through the external primary shaft and a pair of the second gear. The third gear is already selected on the inner shaft. When slowing down, the same operations occur in reverse order. The transition takes place almost without breaking the power flow and at a fantastic speed. The serial Golf box switches in eight milliseconds. Compare with 150 ms on the Ferrari Enzo!

Dual-clutch boxes are more efficient and faster than traditional mechanical ones, as well as more comfortable than automatic ones. Their main drawback is the high price. The second problem, an inability to transmit a high torque, was solved with the advent of Ricardo’s DSG on the 1000-hp Bugatti Veyron coupe. But for now, the fate of most supercars is semi-automatic transmissions. Although, for example, the Ferrari 599 GTB Fiorano box is not a match for Opel’s Easytronic: the switching time of the super robot is estimated in tens of milliseconds.

Today, not only Volkswagen has DCT boxes, but also BMW, Ford, Mitsubishi and FIAT. Preselective boxes have been recognized even by Porsche engineers, who use only proven technologies in their cars. Analysts predict that, in the future, DCT and CVTs will be the most common transmissions. And the days of the third pedal, it seems, are numbered — soon it will disappear even from the best sports cars. Humanity chooses what is more convenient.

This is a translation. You can read the original here: https://www.drive.ru/technic/4efb332e00f11713001e3f50.html

Published November 18, 2021 • 5m to read