The fact that billionaire Bill Gates and the investment company Khosla Ventures decided to invest millions in EcoMotors, a company that designs opposed-piston engines, prompted us to consider this development in detail. Such engines have a long history, but they aren’t widely used, at least in road transport. EcoMotors has put a spin on what would seem to be an already known development.

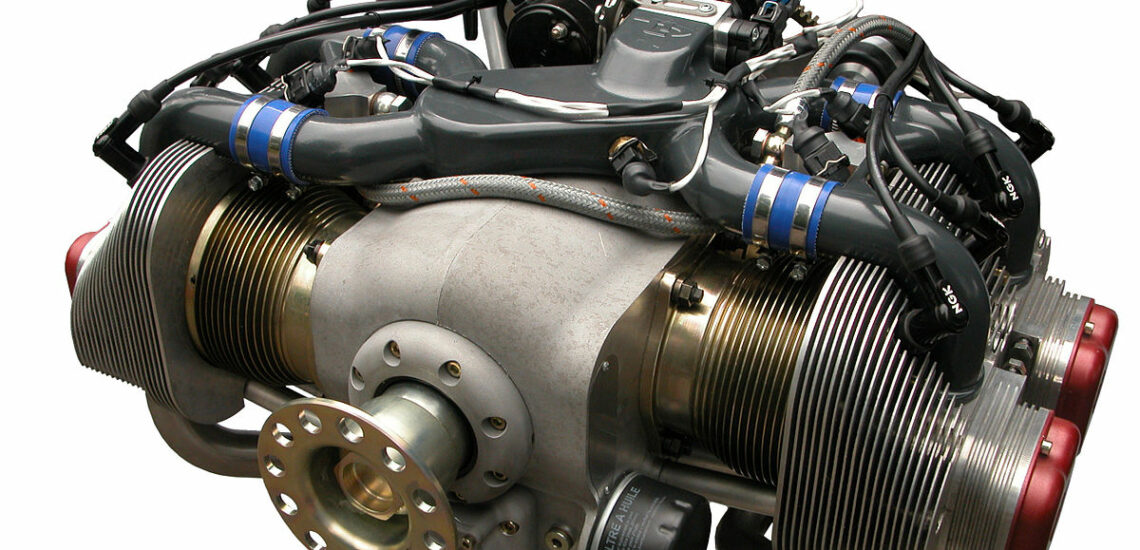

EcoMotors called its engine with two opposed cylinders, each of which has two opposed pistons, uncomplicatedly – OPOC, which stands for Opposed Piston Opposed Cylinder. Technically, both a gasoline engine (or an internal combustion engine that consumes alcohol) and a diesel engine can work under this scheme, but so far the company has focused on the second option.

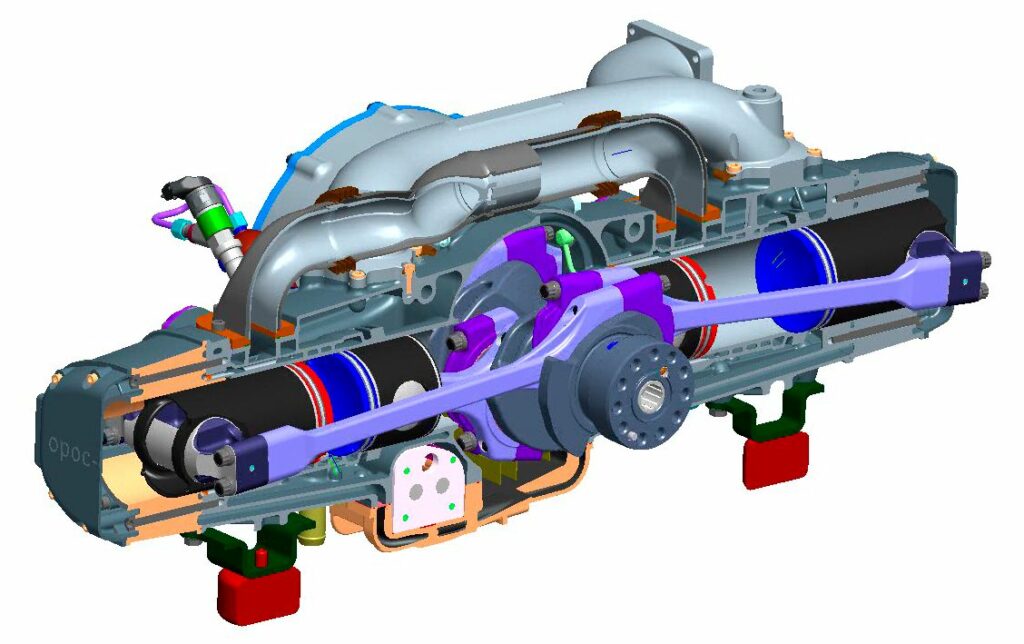

The OPOC engine is two-stroke, so that the opposed pistons of each cylinder make a working stroke in one revolution of the crankshaft. When moving to their dead points, they open windows in the walls of cylinders. And one of the pistons controls the intake, the other – the exhaust. At the same time, the windows are arranged so that the exhaust one opens a little earlier and closes also earlier than the intake one. This is important for good gas exchange.

The removal of cylinder heads, valves and their operating mechanism simplified the engine, made it lighter, reduced friction losses and even oil consumption (according to the company, these indicators became half as low as those of a conventional diesel). But after all, other two-stroke engines with opposed pistons also seem to be able to boast of such advantages, right?

The highlight of the novelty is that all the pistons in it are connected to a single central crankshaft, while previously similar designs required two crankshafts on the edges of the engine. Hence, they were noticeably larger and heavier, and it is not surprising that they were used mainly on diesel locomotives and ships. Well, the OPOC engine is aimed at a much wider range of transport.

Like any two-stroke engine, the OPOC one needs an external device to blow the cylinders when the windows are opened. In this case, the designers decided to impose this duty on the turbocharger. But obviously, it won’t help when the engine starts, and the cylinders themselves are not able to “inhale” and “exhale”.

The solution was again found in a long-standing idea that a number of companies tried out, but no one got it into shape. The engineers installed an electric motor on the shaft of the classic impeller. At the start and until the internal combustion engine picks up speed, this motor receives energy from the batteries, providing the “breath” of the OPOC engine. And then the motor turns off, and the turbocharger turns into the most ordinary. Moreover, at high speeds, when the exhaust gas flow is large, the electric motor in the turbine can turn into a generator that feeds the car’s batteries.

According to its creators, the new scheme is characterized by a very good purge of the cylinders, and therefore makes it possible to get the most out of the two-stroke cycle itself, theoretically allowing to achieve twice the power-to-volume ratio compared to a four-stroke one. Although such performance hasn’t yet been achieved in practice. The OPOC system has a number of other interesting features.

With the new configuration, each of the pistons needs to cover half the distance in one stroke to provide the set working capacity. This means a lower piston speed at a fixed engine speed, and therefore less friction loss. The OPOC engine owes all these features primarily to Peter Hofbauer. The founder, chairman and CTO of EcoMotors previously led the development of advanced engines at Volkswagen for many years. For example, the Vee-Inline VR6 engine with a small (15 degrees) V-angle between the cylinders is under his belt. Although EcoMotors was founded in 2008, Hofbauer himself started thinking about OPOC a few years earlier.

According to the company, the diesel OPOC version is 30-50% lighter than a conventional turbo diesel engine of the same power, contains 50% less parts, takes up two to four times less space under the hood and can be (under certain conditions) 45-50% more fuel-efficient. The latter number raises the greatest doubts among experts, however, even if the saving in consumption is exaggerated, EcoMotors has grounds for optimistic statements. The first prototype of the OPOC internal combustion engine, according to the company, spent more than 500 hours on a chassis dynamometer. It can be stated that the scheme works. But the situation is not so clear with the characteristics. The EM100 model, which is currently being tested by engineers, gives the declared parameters for power and torque only with the settings that don’t take into account the toxicity of the exhaust. The company offers to install such a version of OPOC on military equipment for which the ratio of output to weight is more important than anything else.

For conventional vehicles, EcoMotors offers to configure the same engines in a slightly different way: for 300 hp and 746 N·m. In this case, they promise the “only” 15 percent improvement in fuel efficiency against conventional diesel engines, but even this looks like a huge step forward, since companies usually fight for every percent. Further savings are possible when combining a pair of such engines into a four-cylinder unit. What used to be an independent motor is being transformed into a module. EcoMotors intends to install an electronically controlled coupling between them. They say, only one module will work at low load, and the second module will join at high load. And since OPOC is well balanced, all the forces acting here compensate each other, and the motor has a minimum of vibrations, then the activation of the “sleeping” half will go smoothly at any time.

The idea is similar to the well-known cylinder cutout in large V engines. But while idle pistons still continue to move up and down in that case, here half of the engine stops completely, and the second continues to work in a favourable mode. In addition, the engineers propose to slightly reduce the maximum output of each module in such a binary scheme — to 240 hp (480 will be developed by the entire unit). In terms of power and weight ratio, it will still be a very decent engine, and it will be possible to achieve maximum fuel economy (the same 45%) and compliance with the strictest standards for exhaust toxicity, the developers say.

For now, OPOC is a raw system, and its designers mostly make promises. But they are optimistic and have started to extend the line. The drawings already show the 75-hp two-cylinder EM65 engine that is slightly smaller in size and weight than the EM100. By the way, they want to make it gasoline-powered. The scope of application of the EM65 is quite obvious: light trucks and passenger cars, including hybrids. A certain guarantee, but not an absolute one of the exotic internal combustion engine’s success is the reputation of its chief designer: Peter gave 20 years of life to Volkswagen. And, by the way, it’s not surprising that his current work echoes the projects of Porsche which stood at the origins of the famous German brand.

This is a translation. You can read the original here: https://www.drive.ru/technic/4efb337600f11713001e5522.html

Published October 21, 2021 • 6m to read