Moscow’s bus service is one hundred years old! On August 8, 1924, English Leyland vehicles began running from Kazansky to Belorussky railway stations. We are publishing their story in full detail, based on materials from the Soviet press of those years, archives of Mosgortrans, and even the Leyland company itself.

Automotive anniversaries are a tricky business. You start digging into a particular story, only to find that “the calendars are all lying.” It’s much the same with Moscow’s buses; in fact, “mechanical omnibuses” operated in the capital even before the revolution. In 1907, Count Sheremetev organized a suburban service using two vehicles converted from trucks, and in 1908, a full-sized, hefty Büssing bus took to the streets of Moscow… But we’ll cover the pre-revolutionary projects another time. For now, let’s move on to the Leylands.

It was the summer of 1924: the country had already said goodbye to Vladimir Ilyich [Lenin], and the first Soviet AMO F-15 trucks had not yet appeared. Here is what the newspaper “Vechernyaya Moskva” (hereinafter referred to as the Vecherka) wrote on August 8: “Projects for a Lenin monument” (the winner, of course, was Ilyich on an armored car), “don’t buy from private traders” (“And on a stormy night, please have pity on me, an unfortunate private trader…”), “electrification of Moscow’s outskirts.” The “Court and Daily Life” section featured: “execution for banditry,” “arrest of a female thief,” “engrossed in their work, the thieves completely failed to notice the police arriving…” Advertisements included: “Public restaurant. Beer 50 kopecks,” “Dentist and technician has returned and resumed practice,” and “Anyone can get rid of sweat, warts, calluses, rats, mice, cockroaches and other parasites” (now that’s a combination!).

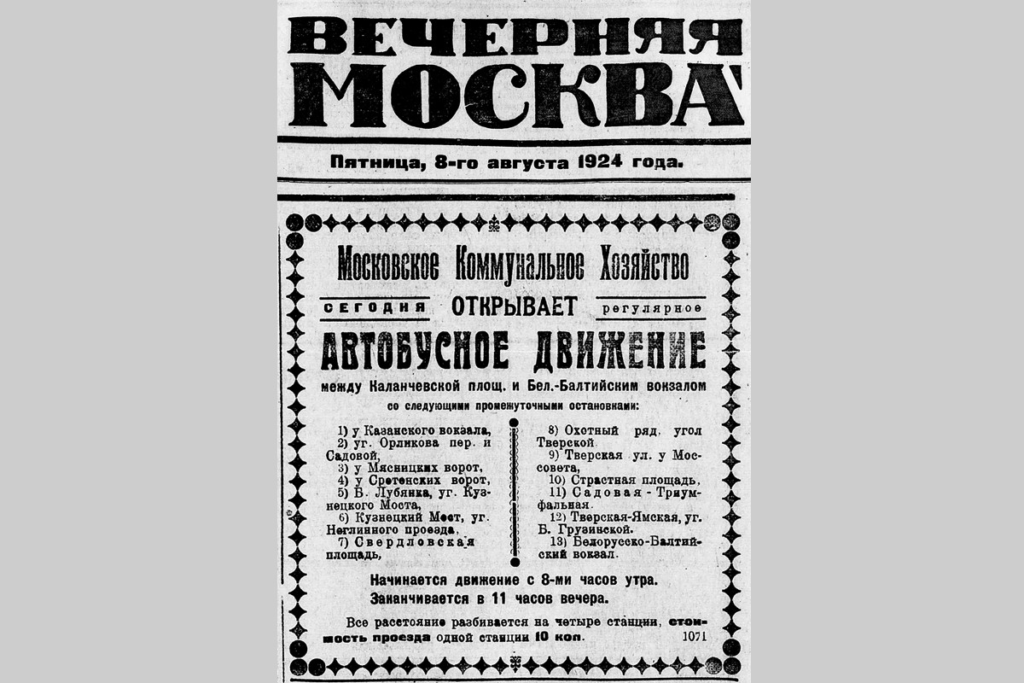

Announcement of the start of bus service, published on the last page of Vecherka

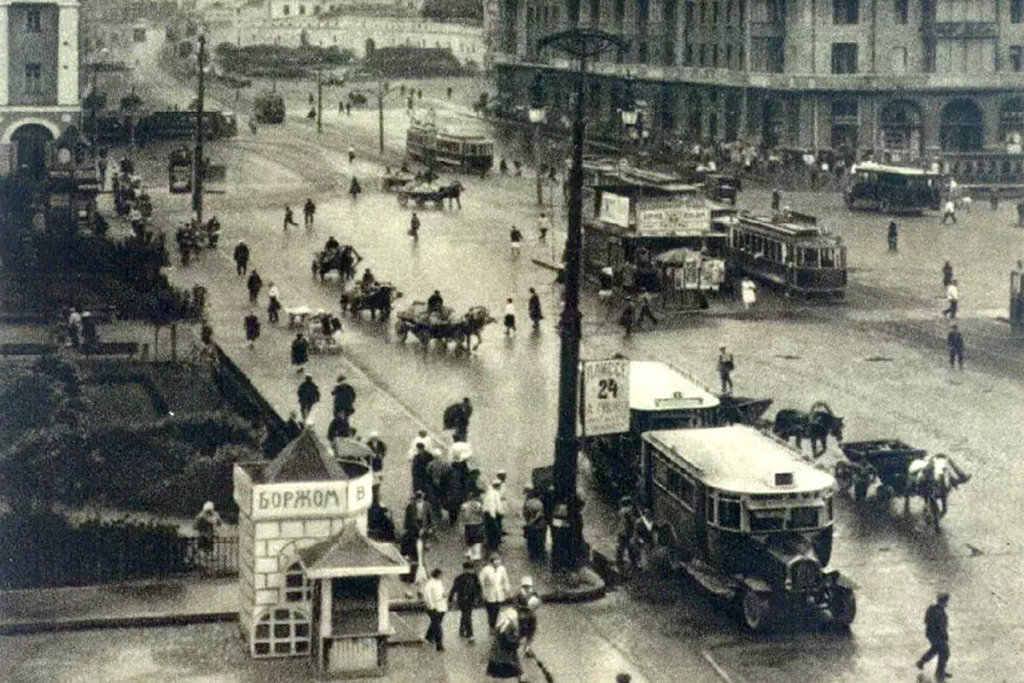

And among everything else, almost in passing: “Moscow’s municipal services today are opening regular bus service between Kalanchevskaya Square and the Belorussko-Baltiysky railway station. Service begins at 8 a.m. and ends at 11 p.m. The entire distance is divided into four stations; the fare for one station is 10 kopecks.”

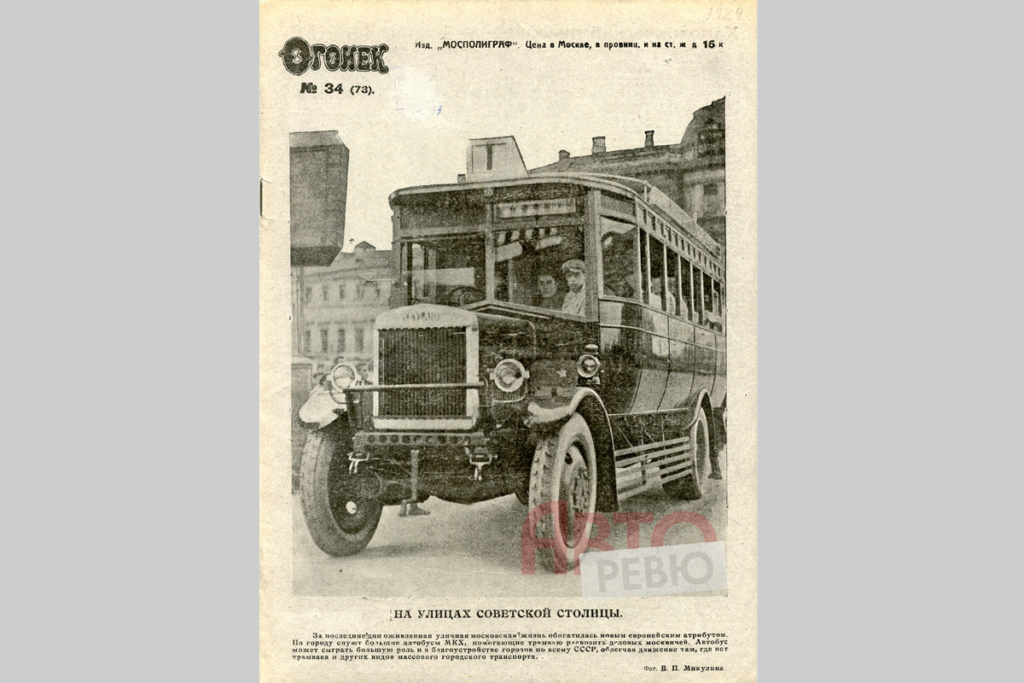

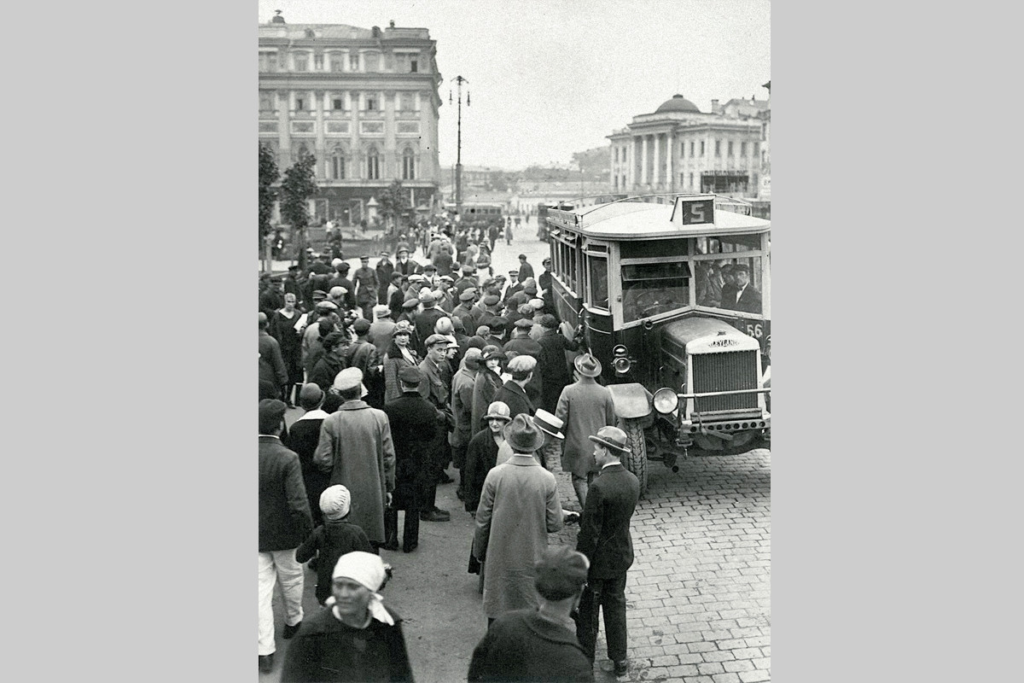

The key word here is “regular”: from that day on, bus service in the city has not been interrupted for a single day. The Moscow press soon realized what a prominent phenomenon the bus was. Photos of Leylands were published in newspapers and magazines, and their drivers were glorified in stories. Here is one from the magazine “Krasnaya Niva”: “On the bus route I take every morning, I’ve grown particularly fond of one driver. <…> His profile is superb—the firm profile of a qualified proletarian. From under the peak of his cap emerges a smooth line… <…> He is always clean-shaven—a rule of the profession. His hands in large gauntlets with cuffs up to the elbows, like those of knights of Brabant, rest calmly on the steering wheel. <…> In his mirrored cubicle, he is just like a poet. Just as solitary, set apart from people, and yet immersed in the boiling of the world…”

And this, from the Vecherka: “He starts the engine, puts on leather gloves, and climbs into the glass booth. <…> From the first steps, trials await him. A peasant woman crossing Kalanchevskaya Square, clattering with empty milk cans, darts about in front of the bus. <…> But the driver doesn’t get angry or agitated. His gaze turns inward, he sounds the horn, he brakes and slips past her…” Can you imagine the clumsy Leyland “slipping” past, and what the drivers actually said while trying not to run over pedestrians?

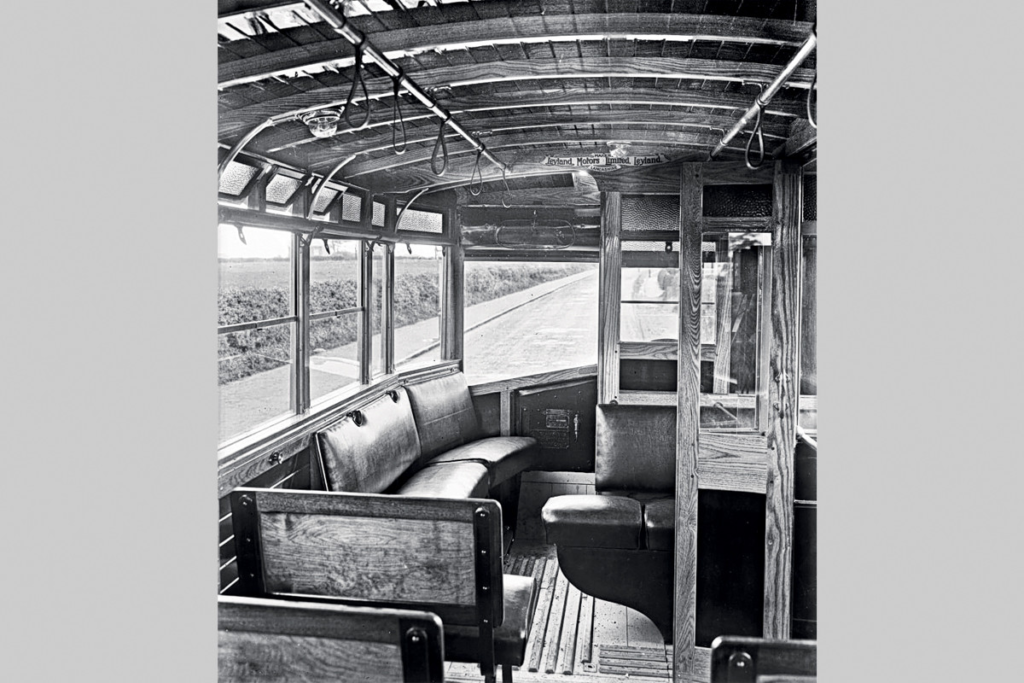

We can judge what these machines were like from surviving memoirs. Driver N.V. Fokin recalled: “I was unbelievably happy when I was offered the chance to master the Leylands: after all, this was new technology. It was hard work… We pressed the stiff pedals and control levers with great effort, and when we braked, we bumped against the hard seatbacks. The buses were started using a heavy crank handle. There was no one-piece windshield, no automatic wipers either, and when it snowed, to see ahead, we raised the top movable glass and the wind with snow lashed our faces. The passenger compartments were unheated. The doors were closed manually. Three weak electric light bulbs provided little light…”

1933, pre-departure check at the first (formerly Bakhmetevsky) park. The crank handle, strapped to the pipe in front of the radiator, is clearly visible.

“To get a Leyland moving was like shifting about ten poods [approx. 360 lbs],” wrote driver Remizov. “When I first got behind the wheel of a bus, I felt strongly what cobblestones were. A bus is harder than a truck. On a truck, you drive, then you rest at a stop while they load. But here, you jolt without stopping.”

From the memoirs of A. Kachalov: “They were so uncomfortable: cramped passenger compartments, suspended straight steps, unreliable doors. It happened that during sharp braking, the doors would swing open and the conductor would fall out onto the ground…”

To become a conductor, one had to pass so-called psychotechnical tests due to the difficulties of the job: the machines shook mercilessly, and exhaust fumes seeped inside. Drivers were often recruited from former horse-cab drivers, who knew the city streets perfectly.

Soon, Leylands became so familiar that their name, like that of Büssing trucks, began to be written with a lowercase letter and without quotation marks, like “xerox” or “pampers.” “Look at the frightened face of a newcomer, who has come to Moscow for the first time, plunged into its roar, the cries of horns and sirens, the clatter of motorcycles and the roar of leylands and büssings,” wrote the Vecherka.

1924, Ogonyok magazine cover, dedicated to the launch of Leyland buses

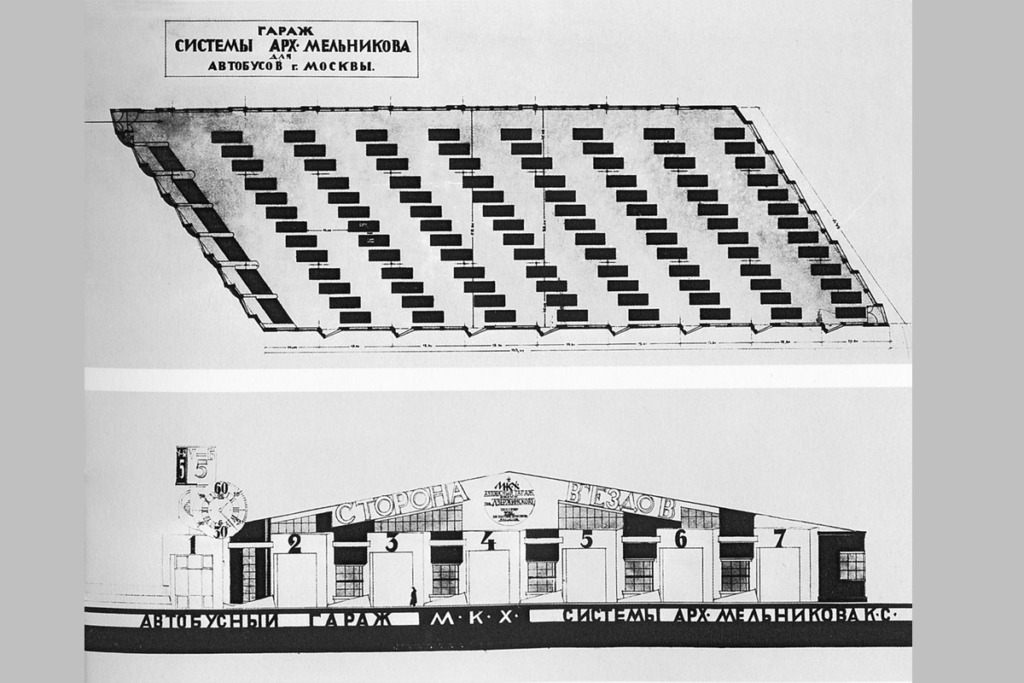

An innovation for Moscow as bright as the buses themselves was the “Bakhmetevsky Garage of the Melnikov system” for 125 Leylands. It was designed by the famous constructivist-futurist architect Konstantin Melnikov (the one who built the crazy cylindrical house for himself on Arbat) with the help of Vladimir Shukhov, author of the lattice Shabolovka TV Tower. When the garage was built, they invited another incredibly talented constructivist, Alexander Rodchenko, for the photo shoot.

A photo from A. Rodchenko’s photo shoot dedicated to the garage. On the right is K. Melnikov.

Garage interior, photo by A. Rodchenko

1926, plan and façade of the “Melnikov Garage”

Melnikov wrote: “Moscow began the construction of a huge manege for the English Leylands. Without delay, I drove at night to Ordynka (where the previous garage was located. — Author’s note) and saw: the foreign dandies (referring to the Leylands. — Author’s note) were being jerked forward and backward, pushed with curses, bedding them down for the night. <…> In my dreams, the Leyland appears to me as a thoroughbred horse; it puts itself in its place. <…> On May 16, 1926, a contract was signed with me for the construction of a manege of a shape unknown to Moscow, an oblique-angled form…”

This is what the garage looks like now: the gate numbers and signs on the façade have been restored, including the white “Entry Side” sign.

The rear of the garage: this is where buses exited.

The modern interior of the Bakhmetyevsky Garage

For the first time in the country, vehicles could enter from one side (it is written there: “Entry Side”) and exit from the other. Rumors spread that Leylands simply couldn’t reverse—but that, of course, is not true.

“Krasnaya Zvezda” wrote in 1933 about what went on in this garage in the mornings: “…The manege shed was filled with the smoke and stench of one hundred and forty ‘leylands’ crawling out onto the route. Urchan crawled under the bus. Stuck his nose into the engine, like a cook into a soup pot. Like a carpenter, he checked the oil through the level’s little glass. And, finally, vigorously cranked the starter handle. <…> With a movement of his hand, Urchan summoned to life the 36 horsepower of the engine; the body was illuminated by light from the battery, it rolled out of the garage. In the far corner, like an outsider, sat the conductor…”

1928, 4 a.m. Buses are getting ready to leave.

But why exactly Leyland? It’s clear that in 1924 we had no domestic bus industry of our own—a few AMO vehicles on imported chassis, not even intended for Moscow, don’t count. But weren’t there other manufacturers abroad?

Of course there were! Do you know how many bus brands existed in Britain alone between 1900–1945, according to the encyclopedia “British Buses”? In words: one hundred and seventy-six! It’s clear that these were mostly coachbuilding firms we’ve never even heard of, but Leyland was, firstly, a major player. Secondly, according to the same encyclopedia, “the most successful,” and also one of the oldest, with an “agency” in pre-revolutionary Russia. Well, and since the young Soviet Union also needed supplies from abroad, its representatives founded a trading company in London, ARCOS — All Russian Cooperative Society Ltd., with its headquarters at 49 Moorgate. All Leyland orders came through it. And now—the chronology.

A 1924 Leyland, but a different model, at the London Transport Museum

1924, March 1. Leyland received the first order from the ARCOS company for eight buses for Moscow. The price of each unit was £1,647.6, or 28,000 gold rubles.

May 24, as the magazine “Motor” wrote, “between Khoroshevsky Serebryany Bor and Krasnopresnenskaya Zastava, three 12-seat Ford buses were launched. <…> On June 5, eight buses began regular service. On holidays <…> one 16-seat Fiat, one 33-seat Büssing, and from two to five 30–40 seat trucks are added.” So, did bus service in Moscow start before August 8? But this route, like Count Sheremetev’s line before the revolution, was considered a suburban summer service and operated only in the summer.

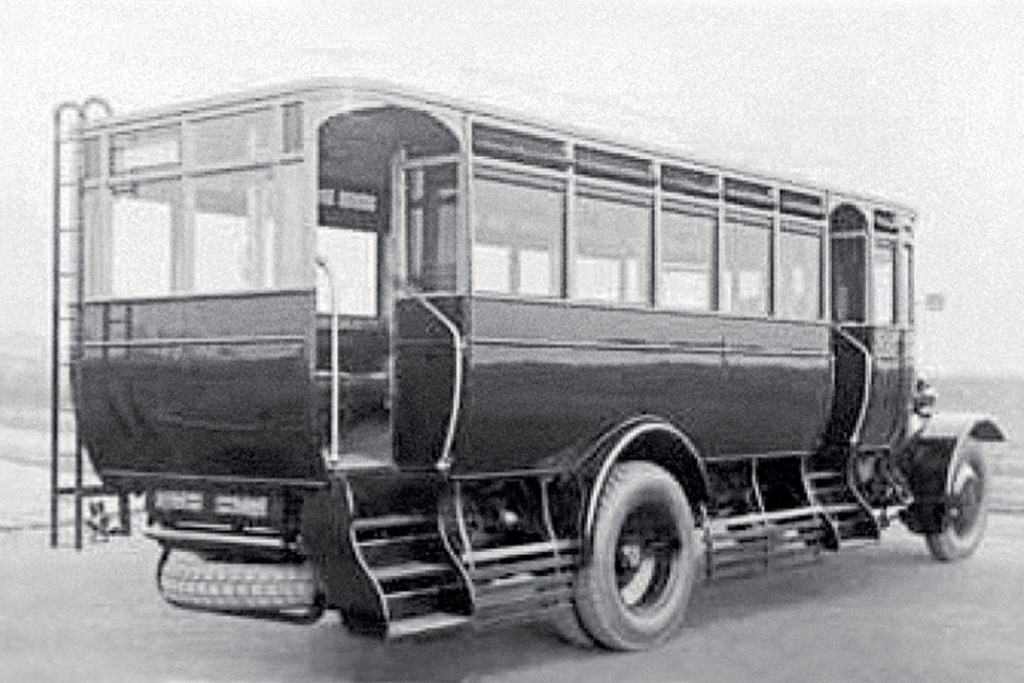

1924, Leyland GH6 Special from the first batch before shipment to the USSR.

The radiator cap bears the British coat of arms; this detail is missing from the Moscow photos.

June. The delivery of Leyland buses took place. It is often written that the model was designated GH7, and this is almost true—but not for the first batch! The fact is that in the twenties, Leyland produced a huge number of bus types: A, B, C, D, and so on up to Z—twenty series, including two-letter ones like LB, GH, and SG, not to mention subtypes with numbers. So, initially, Moscow was supplied not with the GH7 model, but with the GH6, and with the prefix “Special”—on a chassis with a double reduction rear axle from a truck instead of a worm gear. The gasoline four-cylinder engine existed in two versions—with fixed and removable cylinder heads, with a power of 36 and 40 hp, respectively. Everything else was typical for those years: a Ferodo cone clutch that “required great effort and engaged with a jerk,” mechanical brake shoes only on the rear wheels, and steering without power assistance. The vehicles were right-hand drive, but the door openings were made on the “correct” [right] side. The body (initially manufactured by Leyland itself) was as follows: a wooden frame, external steel cladding, internal—plywood with plank lining, a wooden-and-canvas roof (initially with slats, later solid). The windows had many small hinged vents. Some benches were placed longitudinally, some—transversely, plus corner seats; the first batch of vehicles had no heating.

Leyland interior: the seats to the left of the driver were definitely the “trump card”!

August 4, tests were held on Tverskaya Street and Leningradskoye Highway—to Petrovsky Park and back. The vehicles were allocated a garage on the corner of Bolshaya Dmitrovka and Georgievsky Lane, where passenger cars had previously been kept.

August 9, the newspaper “Rabochaya Moskva.” “Yesterday at 12 o’clock, regular bus service was opened from Kalanchevskaya Square to Tverskaya Zastava.”

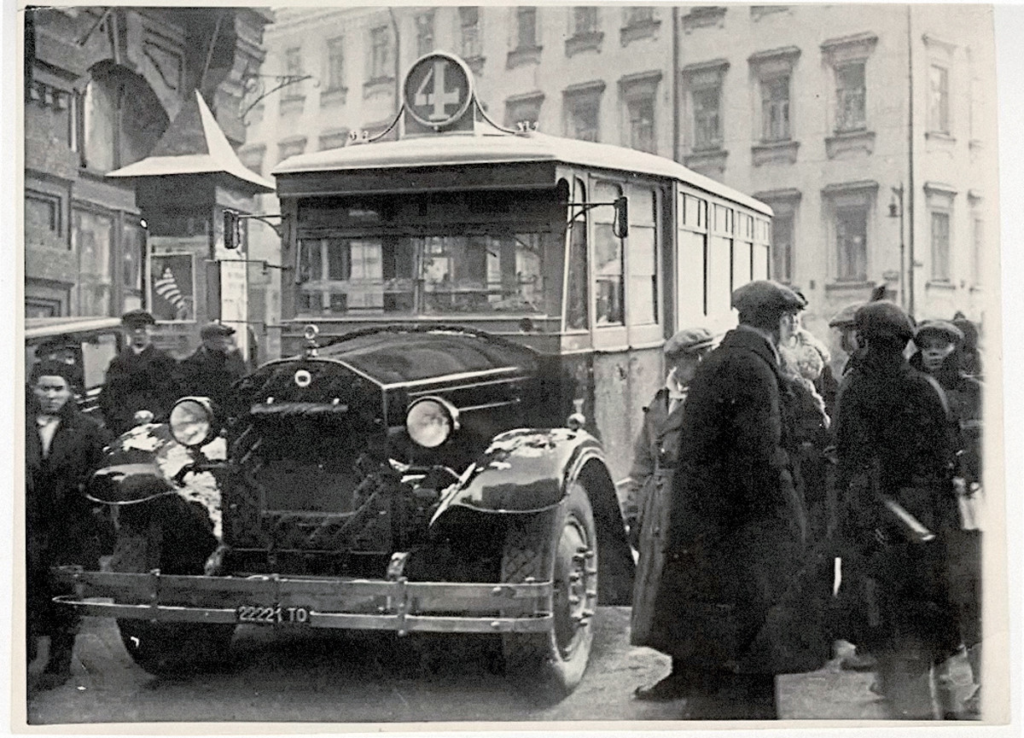

A Leyland from the very first delivery: this is clearly visible from the door placement and configuration. The roof shows some of the stops along Route 1.

1925, January. Mosgortrans veteran A. Gonyaev recalled: “…The second batch, 16 machines, arrived. On these buses, according to the drawings of the automotive sub-department, the arrangement of the front and rear exits was changed, and with it the arrangement of seats inside the passenger compartment. According to the Leyland firm’s price list, this bus type was named ‘Moskva’.”

A production Leyland GH7 Special for Moscow, September 1925. Visible are the repositioned and modified door openings, different wheels, rearview mirror, and side emblem.

A bus from the second batch with a Ham Works body: initially, there was a step ladder on the rear.

They already bore the factory index GH7 Special, were shod with different tires (according to Leyland data, not 1085×185, but 40×8), and were equipped with different bodies—produced by the Ham Works coachbuilder from Kingston. The door openings were moved back (the rear one was located at the very rear), their upper part was made in the form of an arch.

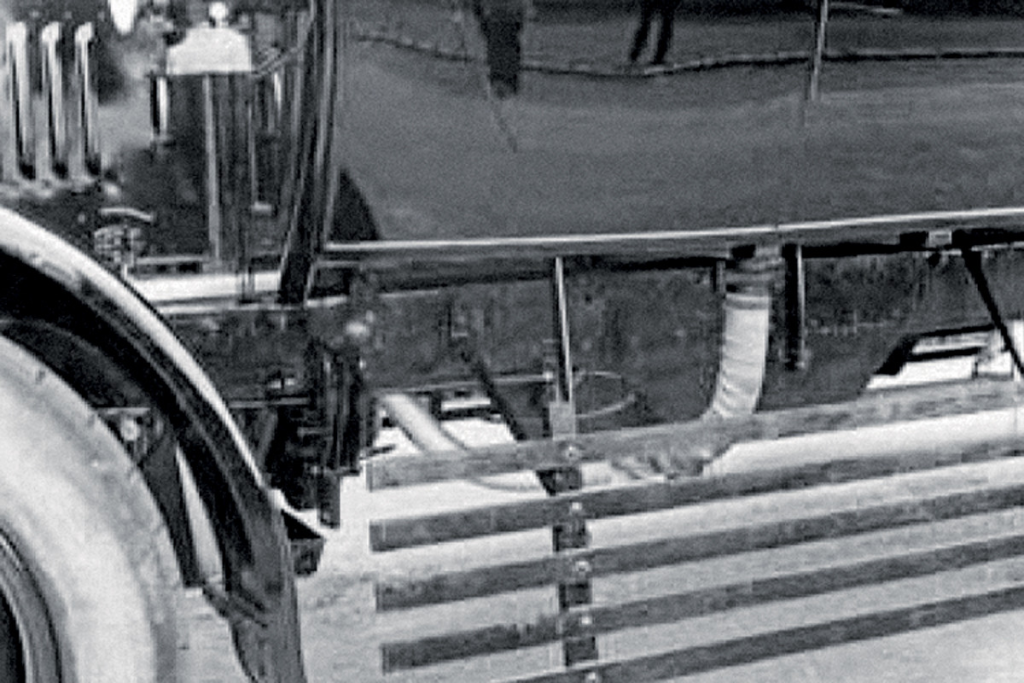

Also, starting from the unit with garage number 122, a number of improvements were introduced: the channel longitudinal members were replaced with stamped box-section members, an electric starter was installed. Heating of the passenger compartment from the exhaust pipe appeared, and even, as English historians write, tire inflation from a compressor.

Exhaust gas heating pipe

Thanks to these buses, two more routes were opened, between Kursky and Bryansky (now Kievsky) stations and between Vindavsky (now Rizhsky) and Paveletsky stations.

March 17, Vecherka: “In addition to the existing 24 buses, another 50 of the Leyland system have been ordered. Furthermore, an order has been placed with Germany for 30 buses of the Mann system.”

May. A bus garage on Bolshaya Ordynka for 110 vehicles was opened; in the same year, the development and construction of the Bakhmetevsky Garage began.

July 7, Vecherka: “On bus route No. 4, a new type of bus of Austrian production, ‘Stayr’ (referring to Steyr. — Author’s note), has been launched. The bus is smaller than the Leyland type, distinguished by a softer ride, but inferior to the English ones in capacity.”

October 4, the newspaper “Sovetsky Sport” published a review from the French newspaper L’Auto: “The bus service on Leylands, carrying ‘comrades’ on Dunlop balloons, is superbly organized.” This referred to Dunlop tires.

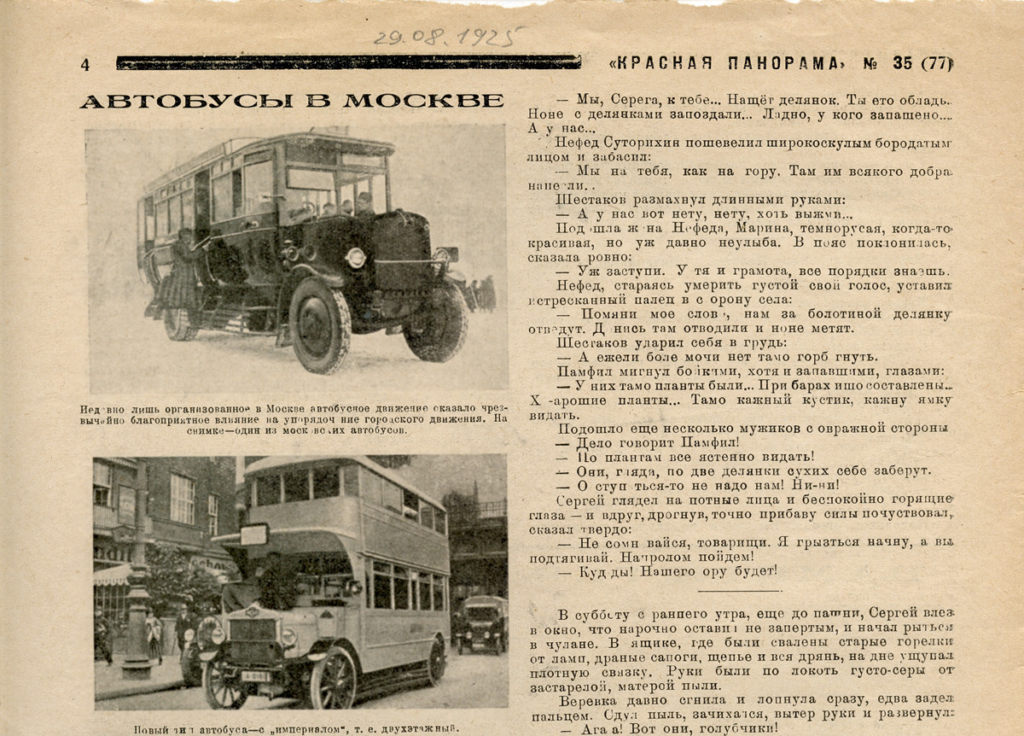

August 1925, article from the magazine “Red Panorama”: insulation is visible on the Leyland’s nose. But there were no double-decker buses in Moscow at the time!

Article from the émigré magazine “Illustrated Russia,” 1926.

October 17, Vecherka wrote that 74 Leylands were operating in Moscow, with another 20 expected in November.

November 23, Vecherka: “Moscow Municipal Services has 122 buses at its disposal. Of these, 86 are in daily operation, the rest are in reserve and under repair. Within the next few days, it is expected to receive <…> 30 MAN buses, 2 Leyland machines, and 6 machines from the French firm Renault.”

MAN bus on Theatre Square, 1927.

It further stated that “Leyland machines <…> exceeded all expectations. The first six, having covered <…> about 70 thousand kilometers, were overhauled and inspected. Their mechanisms were found to be in excellent condition…”

A brochure titled “Avtobus,” published the same year, echoes these publications. “…The machine from the English firm Leyland was well chosen. The four-cylinder engine works flawlessly and almost silently (no worse than some six-cylinder ones) and consumes, despite the bus’s weight of 440 poods (about 7.2 tons. — Author’s note) and a load capacity of 4 tons, only 0.8 pounds of gasoline (0.33 kg. — Author’s note) per hour, less than some passenger cars.”

1926, May 17. Vecherka reported on a Leyland fire: “The shoffer (this word could be spelled with two ‘f’s. — Author’s note) managed to cut off the fuel supply to the engine, thereby preventing the tank from exploding. Meanwhile, the fire, bursting from the carburetor, spread to the driver’s cabin and the interior of the bus. Firefighters were called; the driver and conductor set about extinguishing the fire with the fire extinguisher and sand they had with them. <…> There were no casualties.”

A year later, the newspaper wrote that the Leyland fire was an isolated incident, and 99% of fires “occur on German machines, where due to strong shaking, the fuel line tubes crack.” The Renault buses also proved unreliable (they arrived as chassis, and the bodies were built by the Moscow AMO plant): they were constantly towed from the line by horse-drawn recovery vehicles. A saying even circulated: “Russian ‘whoa!’ and ‘giddy-up!’ haul the French Renault.” Therefore, such machines were soon offloaded to the provinces.

1927, a Renault bus (apparently with an AMO body) – no longer in Moscow, but in the Caucasus

August 4, Vecherka: “…The English firm Leyland cannot provide us with sufficient credit. Therefore, despite the good quality, <…> negotiations have been suspended for now. <…> German firms provide sufficient credit, but experience with Mann machines says caution is necessary. The same applies to French firms. <…> A tangible result has been achieved with the Italian firm Lianchia [Lancia]. <…> If the negotiations are successful, 100 buses will be ordered.” However, Lancia remained a single specimen, and the British were eventually persuaded.

Early 1930s, a Lancia bus on the streets of Moscow

1927, January 4, Vecherka: “…English buses will begin arriving in Moscow from the end of February. A total of 50 machines from the firm Leyland will be received, 10 pieces monthly.” Again with bodies from another manufacturer, Vickers (Leyland itself was overloaded with work due to a flood of orders), but with an already established design. Meanwhile, Moscow decided to reduce costs (by that time Leylands cost £1,938, or 32,000 rubles) and began manufacturing bodies “of the Leyland type” on its own.

One of the early Leylands in front of the Bolshoi Theatre: a curious detail is visible – a loudspeaker under the canopy, which was equipped on the No. 3 route

February 18 Vecherka reported that at the AMO plant, “a body for a Leyland bus with 27 seats has been released. We changed the layout <…> and it is much more spacious than the Leyland buses we receive from abroad. In our bus, there is no middle partition, the seating is better arranged, the body is reinforced. <…> In ten days, it will be handed over to Moscow Municipal Services and will begin running through the city.” In the same year, the AMO workers made a batch of buses on Yaroslavl Ya-3 chassis with bodies similar to Leyland, only more compact. But later, the production of bodies “of the Leyland type” was taken up by the Guzheproizvodstvenny Zavod (Cart Production Plant) of Moscow Municipal Services, which from 1930 was called AREMKUZ.

April 25, Moscow Municipal Services engineer Vasily Kaloshin developed a draft design for a Soviet bus body on a Büssing truck chassis, and a three-axle one at that—the model taken was, of course, the Leyland.

1928, a note from Ogonyok magazine: a unique three-axle bus made in Moscow on the chassis of a Büssing truck

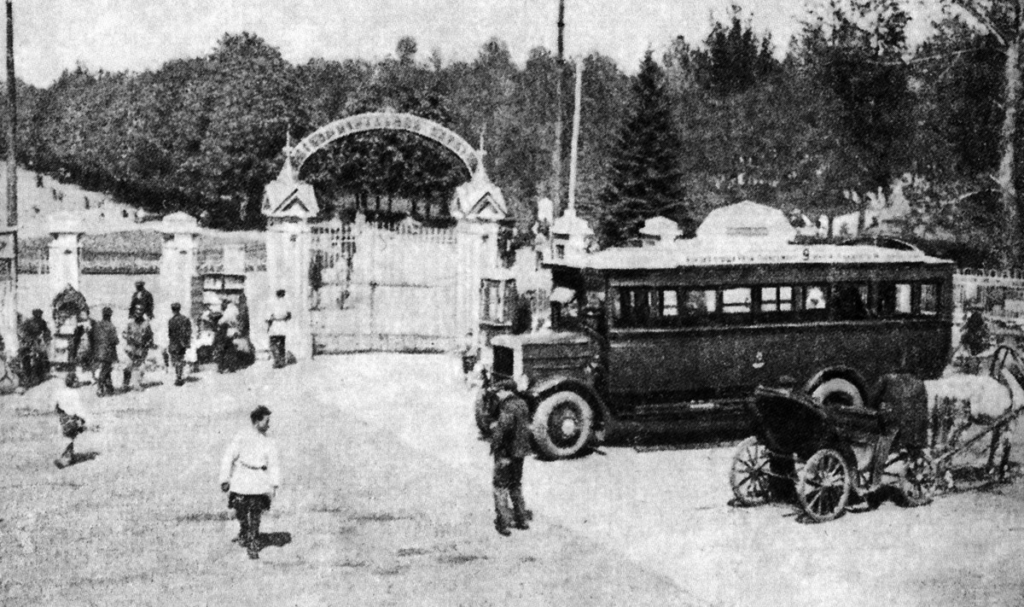

April 29, Vecherka. “Moscow Municipal Services has received 13 Leyland buses from abroad. In connection with this <…> a suburban route Moscow — Ostankino will be opened. Further, as machines are received, <…> Cherkizovo — Center and Losinoostrovskaya — Center. By May 15, the arrival of one bus from the firm Mann of a new design is expected.”

1927, Okhotny Ryad, photo by A. Shaikhet. Bus No. 56 was manufactured in 1925.

September. At AREMKUZ, another five bodies of the Leyland type were laid down, but they could not be manufactured by the end of the year: there was neither the tooling nor qualified workers.

November 1, the Bakhmetevsky bus depot opened. Sixty Leylands were transferred here from the Ordynsky park.

1931, Bakhmetyevsky Park. Bottom left to right: Leyland No. 200 (1928, body by AREMCUZ), No. 31 and No. 49 (both 1925, but with different roofs: No. 31 may have been overhauled)

1928, April. Construction of the Bakhmetevsky depot was completed.

July 23, Vecherka: “New buses from the firm Leyland will begin arriving in Moscow. The first batch is expected in early August. Over three months, 30 machines will be received.” But the deliveries dragged on for almost half a year.

September 23, “Krasnaya Zvezda” reported on tests of “gasoline-benzol” fuel, cheaper than pure gasoline, which was imported—on two Leyland buses, two AMO one-and-a-half-ton trucks, and two Steyr passenger cars.

In January 1929, the only Leyland Long Lion LSC3 arrived in Moscow

1929, January 24, Vecherka: “…from London, the first batch of chassis for new buses has been dispatched. Ten should arrive at the Leningrad port in the coming days. If the port doesn’t freeze and the cargo is received on time, Moscow Municipal Services will already make bodies for the new chassis by the end of February. By March, the arrival of the remaining 20 chassis is expected.

On an experimental basis, Moscow Municipal Services has ordered 1 Leyland bus, made to the latest model. <…> It is larger than the old buses. To prevent accidents during boarding, the new machine is equipped with a special grille <…> the doors are wider than usual and have two steps instead of three. The seats in it are more spacious <…> the engine is significantly more powerful. In the coming days, the bus of the new system will be tested on central streets, as well as on suburban routes. If the new machine suits <…> then in the future Moscow Municipal Services will settle on this type of bus.”

This refers to the Long Lion LSC3 model, long-wheelbase and with a short hood. It remained a single specimen—perhaps because when the Moscow delegation was arranging the supply of this model in December 1928, it had already been out of production for three months!

February 14, Vecherka. “11 (error—10. — Author’s note) chassis from the firm Leyland have been received in Moscow. Bodies of Soviet production have been fitted to these chassis. <…> Moscow Municipal Services intended to strengthen some routes after the arrival of the new buses, but this could not be done, as during the recent frosts, 16 old buses broke down.” The Moscow bodies were identical to the English ones. Also, during 1929, all 177 machines previously listed in the Ordynsky park were transferred to the Bakhmetevsky depot.

1930, stop at Pushkin Square. In the 1930s, Leylands no longer had mirrors, large horns, or extra headlights, and route signs were located not on the roof, but behind the windshield and on the right side of the body.

1931, December 29. Vecherka informed that AMO and Ya-6 buses began to arrive on Moscow routes. Here is what is written about this in the Mosgortrans “History of the Moscow Bus”: “Having refused the mass import of foreign buses, Mosgortrans placed an order with the Yaroslavl Plant for the manufacture of 100 Ya-6 chassis. The production of bodies was handled by AREMKUZ and the central bus workshops. Since they could only make bodies of one type, the Leyland, on the Ya-6 chassis arriving in Moscow, only such bodies were mounted (more precisely, Leyland-Moskva bodies with offset doors). In appearance, the ‘Yaroslavkas,’ as these buses were called working in the capital, differed from the Leylands only in the left-hand placement of the steering wheel. In total, in 1930–1932, Moscow received 101 Ya-6 buses.” The only issue was that all of them, unlike the Leylands, were without heating…

I-6 with AREMKUZ body

1932, February 3, Vecherka. “The London firm Leyland has sent Mosavtotrans a thick book <…> stating that this year it can offer any number of buses <…> undertakes to supply each machine with any number of spare parts. Mosavtotrans no less politely replied that it is forced to decline the services of Mr. Leylandd <…> we no longer need machines from Leylandd and Büssing. We have learned to make our own buses and trucks. <…> Leyland buses ran for seven years on route No. 1 from Tverskaya to Kalanchevskaya Square. Today, not a single ‘Englishman’ remains on line No. 1.”

1931, Petrovka Street, photo by B. Ignatovich. The Leylands display garage numbers 130 (a 1925 delivery) and 172 (a 1928 AREMCUZ body). Note: all the roofs no longer have route signs.

March 15, Vecherka: “The Plant named after Stalin in 1932 will give Moscow 400 units of 28-seat buses <…> by the end of the year, Leylands will become a rarity. They <…> will get lost in the general mass of our Soviet buses.”

September 16 Vecherka questioned: “Is it worth us continuing to make buses based on the Leyland type? <…> …Despite their long service, the leylands <…> are very unstable, shaky, and have low capacity.”

September 25 Vecherka proposed increasing the capacity of Leyland and Ya-6 buses by using trailers.

Coat of arms on board Leyland

1933, January 6. Vecherka published a critical article “The Bus with Shortness of Breath.” “A huge percentage of machines <…> returned to the depots due to lighting malfunctions <…> For the repair of Leylands in the Bakhmetevsky depot, there exists a microscopic workshop. No one checks the quality of the repairs. A repaired bus often returns to the workshop from its very first run. The Yaroslavl Ya-6 is repaired somehow by the AREMZ plant <…> the newest AMO-2 and AMO-4 are repaired by no one <…> there is virtually no rapid technical assistance in Mosavtotrans. In emergencies, this role is performed by trucks that don’t even have a full set of wrenches. It happens that when going out to a breakdown, drivers rush about looking for a simple rope.”

Decoration of the Leyland propaganda

August 29, Vecherka: “The Leylands began to give out. The other day, Mosavtotrans wrote off the first 15 veteran machines due to technical faults. Over 9 years, they have clocked up 800 thousand kilometers each.” A mileage worthy even of today’s technology! Further, the note mentions negotiations on building a double-decker bus at ZIS. Double-decker trolleybuses appeared in Moscow before the war, but buses—alas.

Near the Novodevichy Convent

1934, February 23. Vecherka explained how to distinguish buses of different routes. “Routes 1, 4, 21 are served by machines from the Auto Plant named after Stalin (small, blue and red), on routes 2 and 3, machines from the Yaroslavl Plant operate (tall, red, driver and number are on the left), on routes 5, 6, and 10—English Leylands (similar to the Yaroslav ones, but the driver and number are on the right).”

June 29 Vecherka reported that it had been decided to paint all capital’s buses in a “de luxe” style and repair their passenger compartments. Inside, route signs would appear, and the headlights would be replaced with brighter ones. In the same year, the major overhaul (essentially, re-manufacturing) of bodies “of the Leyland type” at AREMKUZ ceased.

Ya-6 buses with Leyland-type bodies at the AREMKUZ plant

September 3 Vecherka raised the question of heating in buses. “Last winter, Muscovites froze in unheated buses. <…> Work has begun on installing heating appliances on the ‘Yaroslavkas.’ <…> Things are alright in this regard with the Leyland. However, 135 buses from the Plant named after Stalin may remain without heating. <…> …We need to obtain either batteries for electric heaters, or special pipes for heating using exhaust gas.”

1935, January 28, “Krasnaya Zvezda”: “Moscow has a bus fleet of 415 motor vehicles. Only about 100 are old Leylands. The rest of the buses are of Soviet production.”

1935, in front of the Triumphal Arch – not a Leyland, but a nearly identical-looking Ya-6 with an AREMCUZ body. The hood flaps were raised: although it wasn’t hot outside, the engine was heating up!

1936. All Moscow Ya-6 buses were written off—as Mosgortrans indicates, due to the low quality of the Yaroslavl chassis, including weak brakes. There is a suggestion that the units (American Hercules engines and gearboxes, Mercedes steering) were sent to a special reserve for Yaroslavl trucks in case of war.

1937, January 11, Vecherka: “We are to receive 500 new buses of the ZIS-8 type. This makes it possible to withdraw from ekspluatatsia the old, worn-out Leylands. By the end of the year, the fleet will consist of 1000 machines.” The word “ekspluatatsia” [exploitation] was then spelled with an ‘o’.

Leyland on Verkhnyaya Maslovka. Judging by the signs on the roof, the photo was taken back in the 1920s.

January 27, 1938, Vecherka: “At the bus stop—a queue. <…> Finally, the long-awaited Leyland appears. <…> Having gone a few dozen meters, the machine turns… And delivers the indignant passengers to the bus depot <…> due to a breakdown <…> of the gearbox.” It further spoke of numerous technical problems with the buses.

1939, August 9, Vecherka: “The Leylands and Fiats have long disappeared from Moscow’s streets…” This is the last mention in the Moscow press of those years about Leylands.

It is clear that not a single one of them has been preserved. Even when Vecherka, for the 50th anniversary of the bus launch in 1974, tried to find anyone connected to them, they only managed to locate a veteran who “as a boy would throw a hook [to hitch a ride] to ride on the tow of a Leyland, which was a common pastime.”

Leyland No. 127 (from the last delivery of 1928, with an AREMCUZ body) at the gas station in front of the Bakhmetevsky garage

All the more unsurprising are the confusion and gaps in the archives. According to Mosgortrans data, the capital received 177 Leylands, but analysis shows there were 175 (in 1928—not 33 machines, but 31, exactly 30 for AREMKUZ bodies and one Long Lion). The fate of the last 15 units sent to the USSR is unclear: the British suggest the destination could have been Kharkov, where 20 Leylands went in 1925, but no records remain at the factory. One can only say that the “Kharkov” bodies were somewhat different from the “Moscow” ones.

One of the first buses in Kharkiv – clearly a Leyland by its appearance

Today, the capital’s authorities, preparing for the opening of the Moscow Transport Museum, have decided to build a 1:1 scale “non-operational mock-up of a Leyland GH6 bus from 1924,” from the very first batch. And do you know how much it will cost? 25,936,989 rubles and 99 kopecks! It’s even known which donor vehicle parts are planned for use: the rear axle, front springs, driveshaft, and headlights—from a ZIS-5 truck; the brake system—from a GAZ-53; the rear springs—from a Valdai. By the way, about the same, around 27 million rubles, will be the cost of manufacturing another non-operational mock-up for the museum—a double-decker YaTB-3 trolleybus, also using components from donor KAMAZ trucks.

A computer rendering of the Leyland model for the Moscow Transport Museum.

But in any case, replicas, even carefully built ones, are not the same thing. If you want to feel the spirit of the time, go to the Jewish Museum… I mean, to the Bakhmetevsky Garage on Obraztsova Street, 11, and reread the words of the brilliant architect Melnikov, written by him in 1965: “At present, we have an abundance of our own domestic machines, and such a tenderly caring storage of them makes no sense <…> but the building I built remains profitable even today…”

Of course. Here are the provided technical specifications, translated into English and formatted in a clear, professional table.

Technical Specifications (Passport Data)

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Model | Leyland GH6 Special / GH7 Special |

| Seating Capacity | 28-29 / 6-7 (Note: The 6-7 figure is likely for standing passengers) |

| Length / Width / Height, mm | 8000 / 2320 / 3150 |

| Wheelbase, mm | 4826 |

| Curb / Gross Weight, kg | 6075 / 9107 |

| Engine, Displacement, L | 6.7 |

| Power, hp | 36 or 40 |

| Gearbox | 4-speed manual |

Of course. Here is the data from the table translated into English, maintaining the original structure and including the notes.

Shipments of Leyland Buses to the USSR (According to Manufacturer Data)

| Year/Month | Quantity | Model | Body Manufacturer | Destination City |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1924/06 | 8 | GH6 Special | Leyland | Moscow |

| 1924/11—12 | 16 | GH7 Special | Ham Works* | Moscow |

| 1925/05—07 | 40 | GH7 Special | Leyland | Moscow |

| 1925/05—08 | 20 | GH7 Special | Leyland | Kharkov |

| 08.10.25 | 30 | GH7 Special | Leyland | Moscow |

| 1927/02—06 | 50 | GH7 Special | Vickers | Moscow |

| 1928/11—12 | 30 | GH7 Special | AREMKUZ** | Moscow** |

| 1928/12 | 1 | Long Lion LSC3 | Leyland | Moscow |

| 1929/01—02 | 15 | GH7 Special | No Data | Kharkov (?) |

| Total | 210 |

Note: Also in 1925, 35 trucks, including fuel tankers, were supplied.

- It is possible that bodies for later batches were also produced by the Ham Works coachbuilder.

** According to Avtorevyu magazine data.

Of course. Here is the data from the table translated into English, maintaining the original structure and clarifying the note.

Deliveries of Leyland Buses for Moscow (According to Mosgortrans Data)

| Year | Quantity | Garage Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| 1924 | 24 | 1—24 |

| 1925 | 70 | 25—68, 11, 113, 114, 116—138 |

| 1926 | 28 | 139—149, 151—157, 159—169 |

| 1927 | 22 | 70, 73—88, 105, 107—110 |

| 1928 | 33* | in the range 170—207 |

| Total | 177 |

Note: Of these 33 units in 1928, 30 were chassis intended for AREMKUZ bodies.

Of course. Here is the data from the table translated into English, maintaining the original structure.

Deliveries of Ya-6 Buses with AREMKUZ Bodies “of the Leyland Type” for Moscow

(According to Mosgortrans Data)

| Year | Quantity | Garage Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 28 | 208—335 |

| 1931 | 65 | (Not specified in original data) |

| 1932 | 8 | (Not specified in original data) |

| Total | 101 |

Of course. Here is the data from the table translated into English, maintaining the original structure.

Number of Buses in Moscow (According to Mosgortrans Data)

| Year, Month | Quantity | By Brand (Breakdown) |

|---|---|---|

| 1925, December | 138 | Leyland — 94, MAN — 30, Renault — 12, Ford — 2 |

| 1929, January | 196 | Leyland — 175, MAN — 16, Büssing — 3, Fiat — 1, Ya-3 with AREMKUZ body — 1 |

| 1932, January | 268 | Leyland — 177, Ya-6 with AREMKUZ body — 65, AMO-4 — 25, Lancia — 1 |

| 1933, October | 369 | Imported — 125, Domestic — 244 |

| 1935, January | 415 | Leyland — 100, Domestic — 315 |

Photo: Fyodor Lapshin

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: Leyland московский: как автобусы из Англии ездили на улицах Москвы 100 лет назад

Published October 09, 2025 • 26m to read