When Mercedes announced the W124, BMW countered with the E34. Munich’s answer was loud and clear with the proclamation of the M5, and Stuttgart was quick to respond with the 500 E. Interestingly, despite the stark differences between these super sedans, they shared a peculiar starting point—both began their journeys in a truck body.

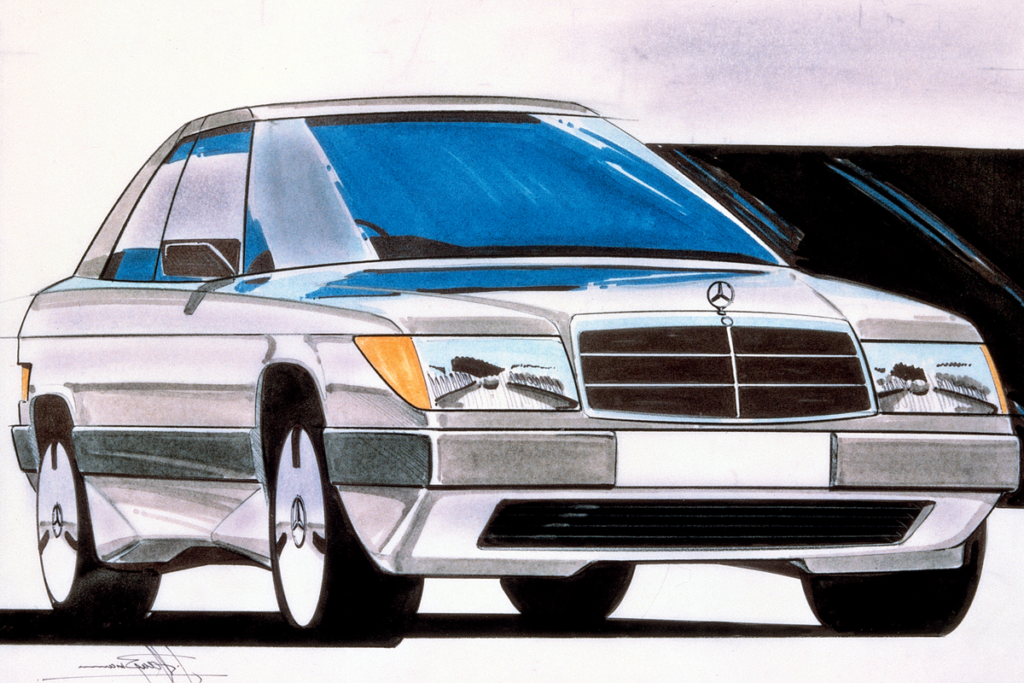

The W124 project began in 1977, with the initial design crafted by Peter Pfeiffer and Josef Gallitzendörfer, and was finalized by the head of the styling center, Bruno Sacco.

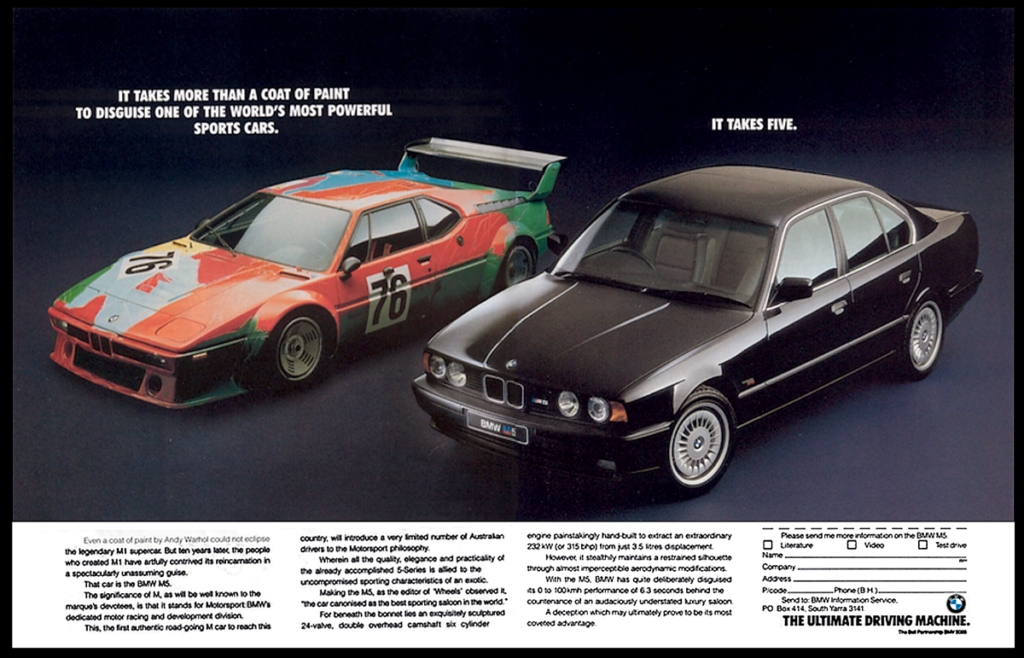

The rivalry’s tone was undeniably set by BMW in the 1980s, driven by an ambition to outpace Mercedes. The competition was so fierce that Munich had to double its efforts just to maintain pursuit. They needed a breakthrough to gain an edge, which came with the launch of the E32 ‘Seven’ in 1986, followed by the V12-powered BMW 750i a year later. The challenge then was to replicate this success with the ‘Five.’

Launched in 1988, the E34 sedans were bred with a singular focus—to outclass the formidable W124. Four years post its debut, the Mercedes still stood as a marvel of automotive engineering. During our retro test, I delved into the BMW Praxis, a dealer catalog used to train sales associates on the new ‘Five.’ This 240-page manual is a treasure trove of details about the E34, filled with insights seldom found elsewhere.

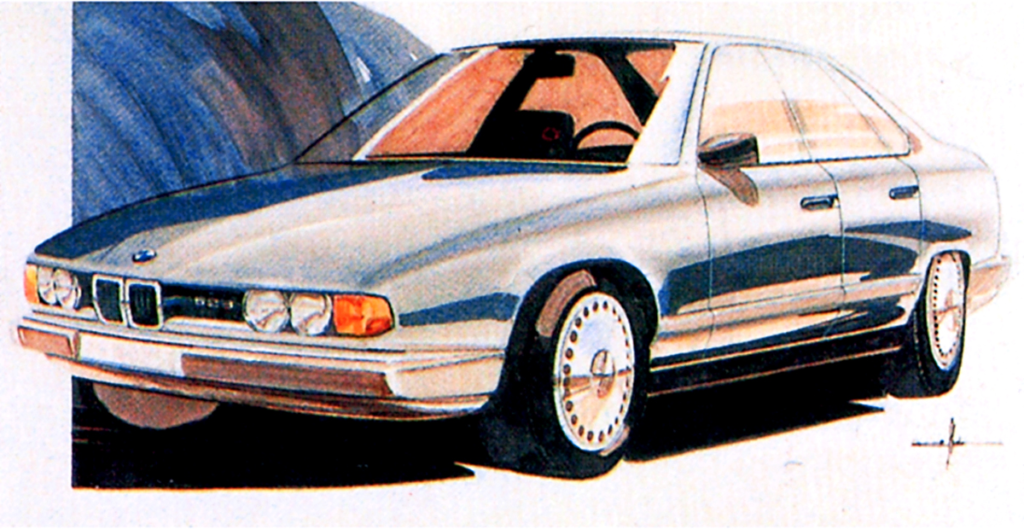

The Italian genes of the E34 were sketched in 1982 by Ercole Spada. The work on the “Five” was continued by Jay Mays, and completed under the guidance of Klaus Luthe.

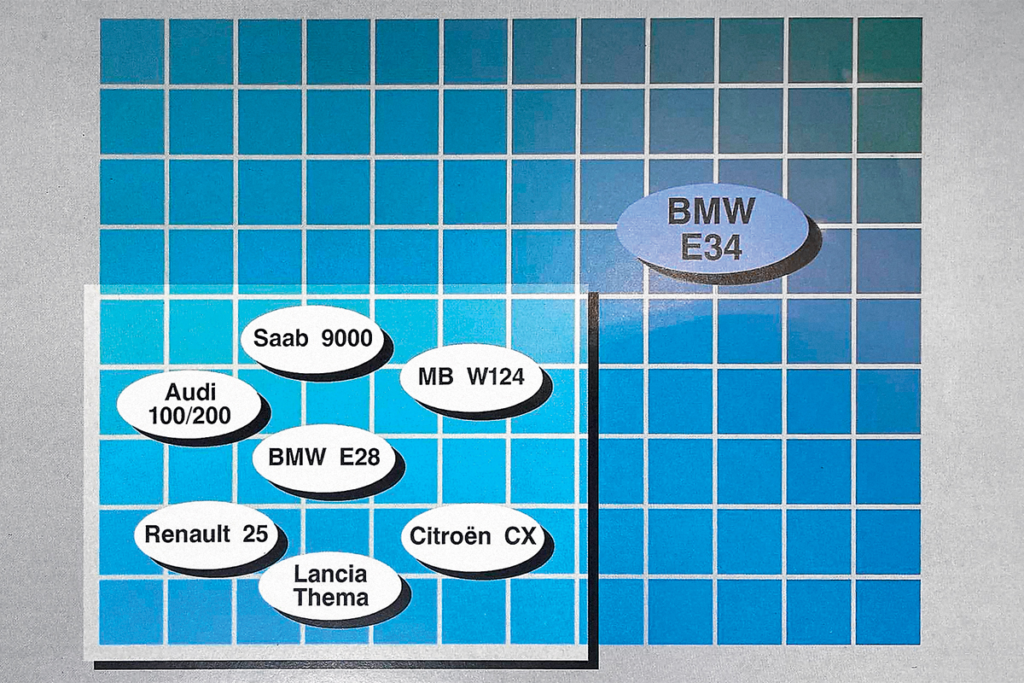

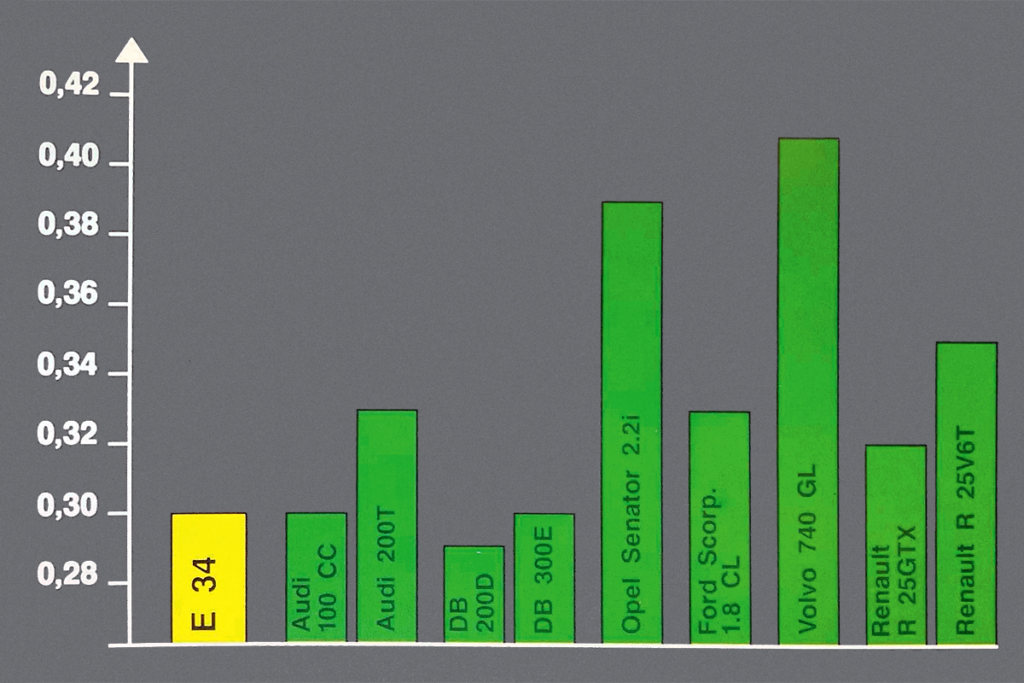

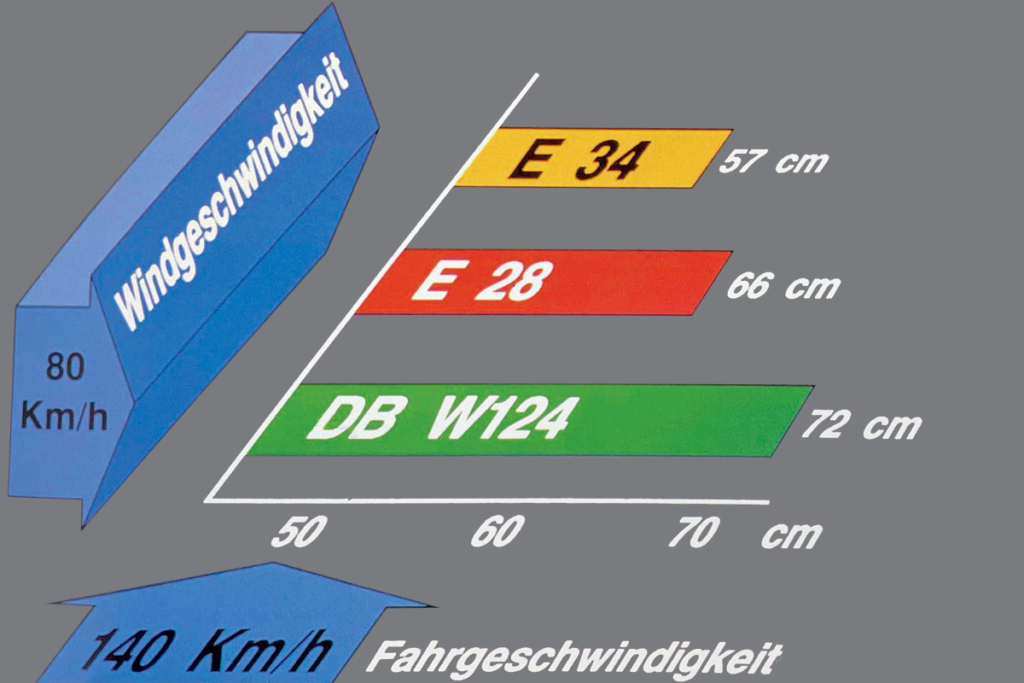

From marketing strategies to technical innovations, the rivalry was intense. BMW analyzed market shares across various professions, noting a preference for the ‘Propeller’ among mid-level managers and the ‘Star’ among top executives and freelancers. BMW also touted improvements in aerodynamics, claiming an 18% improvement over its predecessor and achieving a drag coefficient of 0.30, all while maintaining its iconic grille design. Subtly, they hinted that their results could have been even better if not for their standard tire policy—a jab at Mercedes, whose best aerodynamic figures were achieved with narrower tires.

The balance between functionality (vertical axis) and aesthetics (horizontal axis) as perceived by BMW. It turns out that Lancia is the least practical, while Audi is deemed the least beautiful.

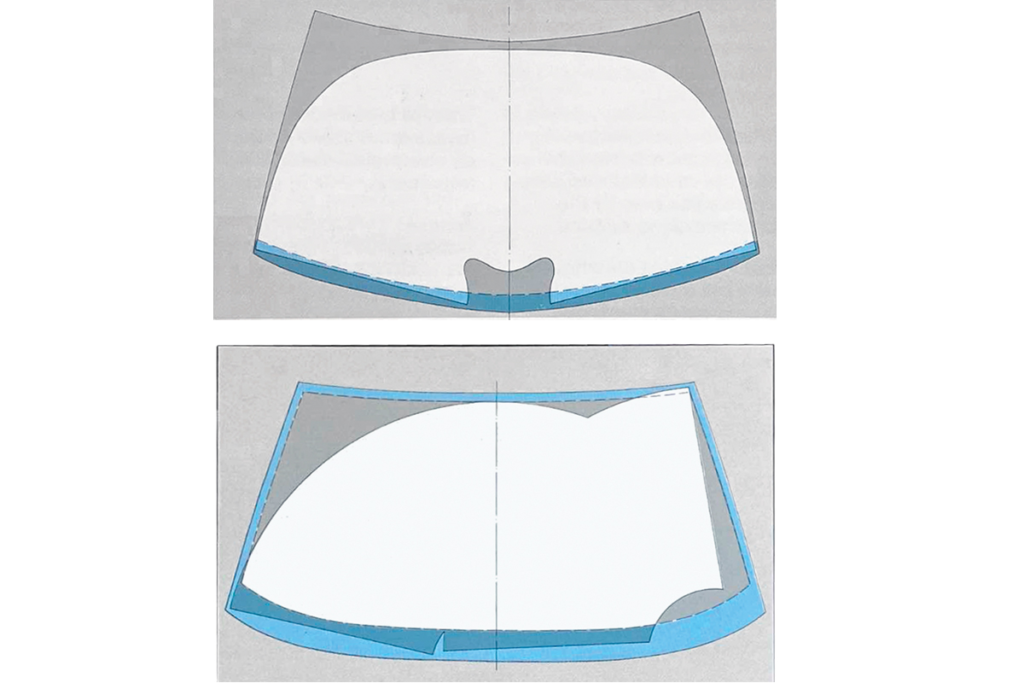

Innovations like Mercedes’s unique wiper system that cleared 86% of the windshield were met with BMW’s extended wipers that matched the cleaning area but added a mechanism for better blade performance at low speeds. Similarly, while Mercedes boasted automatic heating for mirrors and jets, BMW introduced a heated lock mechanism activated by holding the door handle—a feature of thoughtful engineering.

It’s evident how differently companies worked with the front end. For Mercedes, the optics and grille act as an aerodynamic tool that helps reduce lift. For BMW, the headlights are primarily the face of the brand. Nevertheless, the BMW Praxis catalog provides intriguing figures: to overcome air resistance at a speed of 180 km/h, the E34 needs 64 hp, and at 200 km/h, it requires 87 hp. This is 20% less than its predecessor, the E28, with a similar shark nose.

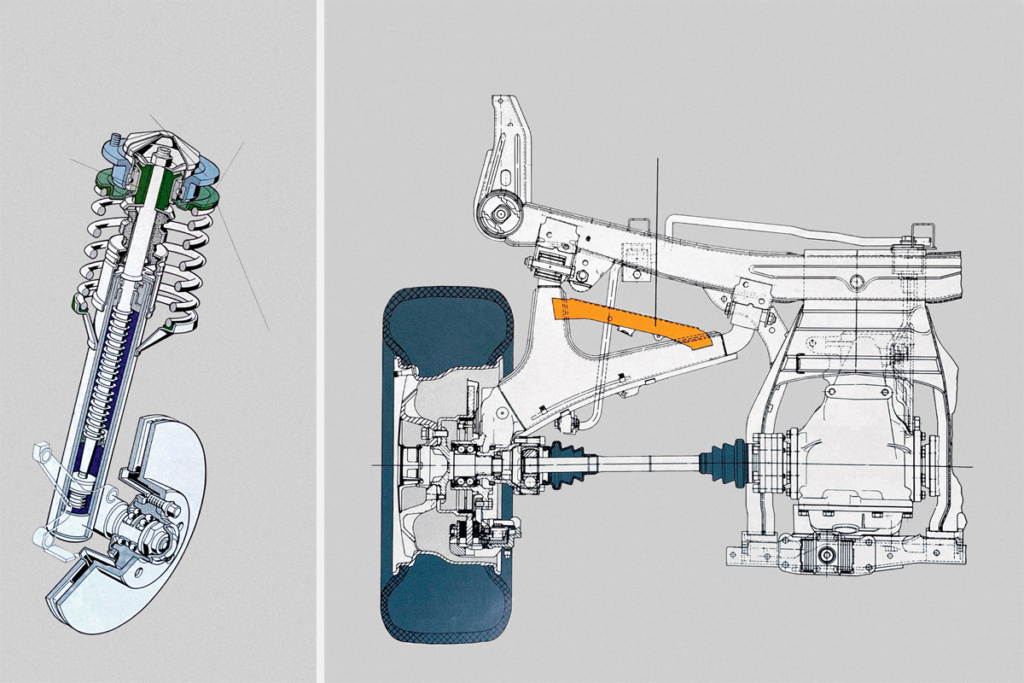

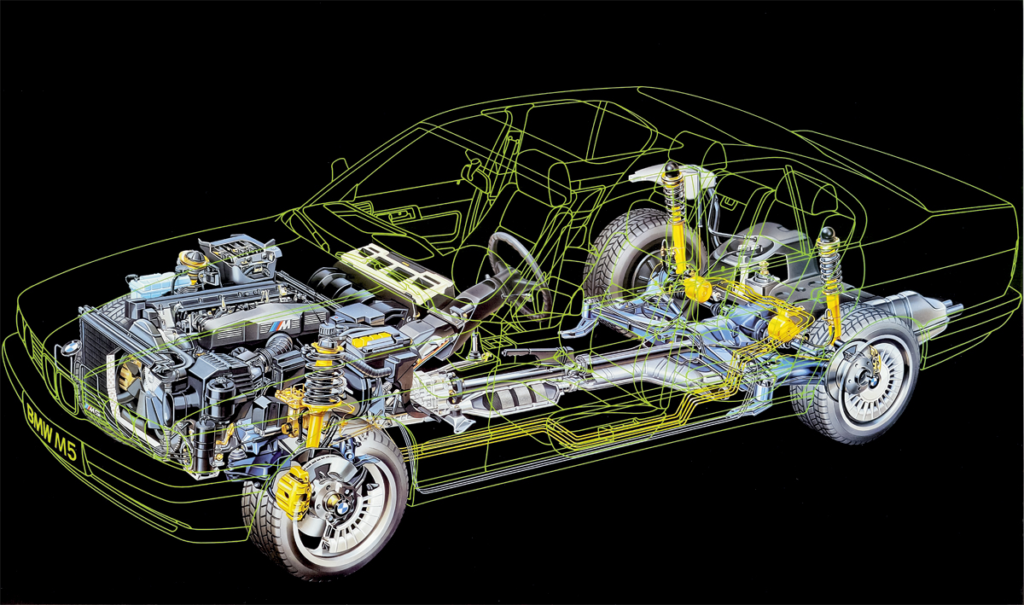

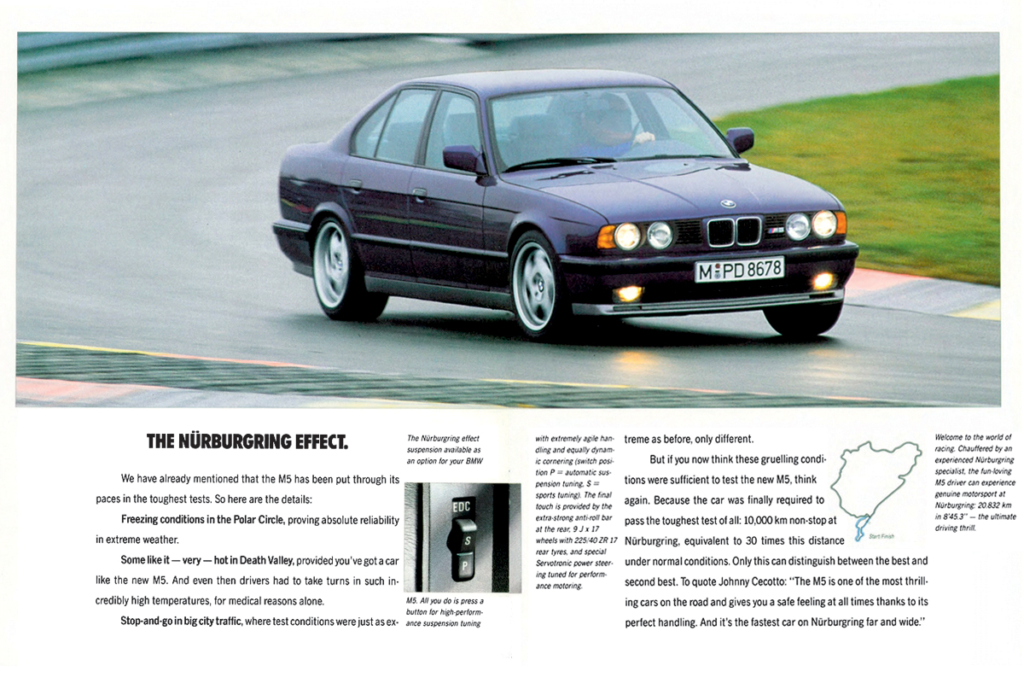

Each model introduced features designed to outdo the other. Mercedes’s famed five-link rear suspension was met with BMW’s enhancements to the E34’s existing setup, including electronically controlled dampers and a Servotronic steering system. BMW also answered Mercedes’s ASR with its advanced ASC+MSR system, which addressed not just traction but also wheel lock during deceleration.

The catalog even provided a rationale for the M5’s handling characteristics, suggesting that BMW intentionally tuned the chassis for neutral to slight understeer that could transition to oversteer with throttle input, presumably to counter the Mercedes’s tail-happy nature.

The aerodynamics of both classics and contemporaries. To catch up with Mercedes, BMW pulled employees from Audi.

This ongoing battle of one-upmanship not only pushed technological boundaries but also underscored a deep-seated rivalry. While the E34 momentarily edged ahead of the W124, it could not replicate the revolutionary impact of the V12 E32. Despite sharing a platform with the ‘Seven,’ the ‘Five’ always seemed a step behind its Stuttgart counterpart, chasing innovations like all-wheel drive and safety enhancements that Mercedes had pioneered.

Mercedes’ wiper reaches the top corners and provides a record windshield cleaning area for the automotive industry. BMW insists that the upper left corner is more important for visibility at traffic lights.

The BMW M5 remains a testament to this fierce competition, embodying the relentless pursuit of automotive excellence and innovation. As these rivals pushed each other to greater heights, they left a legacy of engineering prowess and performance that continues to inspire the automotive world.

Another reason to highlight superiority over Mercedes: in side winds, the E34 drifts less than the W124.

When Mercedes introduced the W124, BMW was quick to respond with the E34, heralding its own masterpiece, the M5. Stuttgart’s counter, the 500 E, marked the beginning of a fascinating rivalry between two distinctly different super sedans, both sharing a surprising origin: each model began its life on a truck chassis.

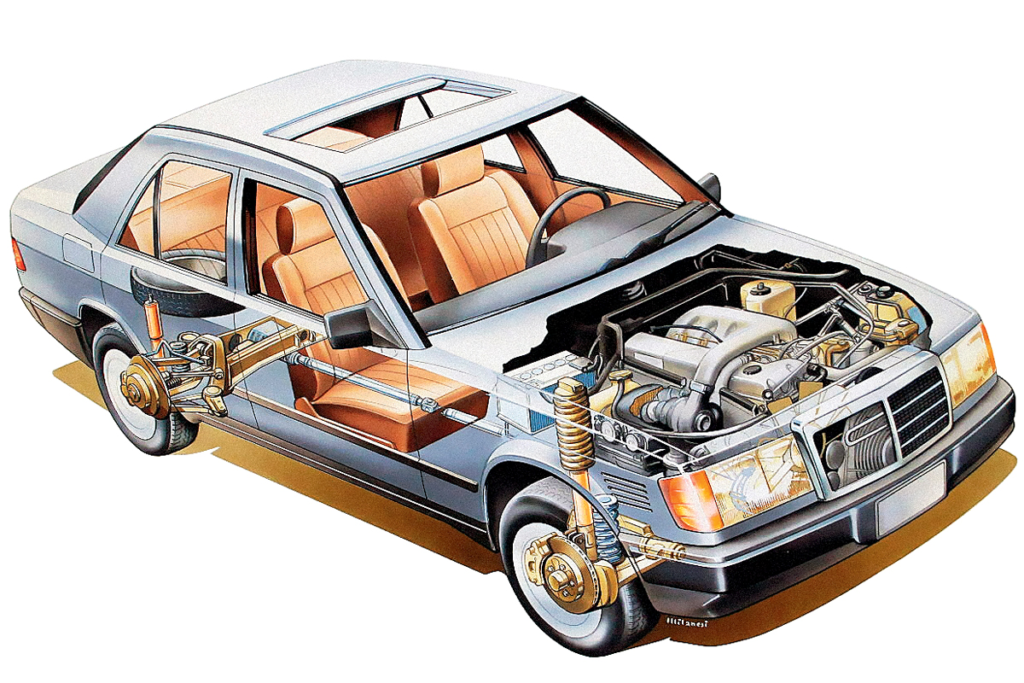

The main technical gem of the W124 chassis is the rear multi-link suspension, which appeared slightly earlier on the smaller sedans W201 and was subsequently installed on almost all Mercedes passenger cars. It has been copied by many other manufacturers. With modifications, this basic five-link scheme is still used today.

The 1980s saw BMW fervently striving to surpass Mercedes. Stuttgart was formidable, forcing Munich to double its efforts just to keep pace. To surpass Mercedes, BMW needed something extraordinary. They delivered in 1986 with the debut of the E32 ‘Seven’ and further astonished the automotive world a year later with the V12-powered BMW 750i. The challenge was to replicate this success with the ‘Five’.

For all E34 versions above the BMW 525i and 524td, McPherson struts with separate spring and shock absorber mounts were provided. At the rear, oblique arms were reinforced with braces. This was the last “Five” with such an old-school rear axle. As an option, except for the M5, a stiffer Sport suspension was offered.

Launched in 1988, the E34 sedans were laser-focused on one target—the outstanding W124. Four years after its debut, the Mercedes still epitomized the zenith of automotive engineering.

During our retrospective testing, I spent several days with a unique dealer catalog, the BMW Praxis, designed to train sales staff on the new ‘Five’. This 240-page bible of the E34 covers every minute detail and design decision of the vehicle. It’s packed with unique insights and commands a price of 30,000 rubles—a testament to its value. Notably, the W124 is mentioned on nearly every page, underscoring an apparent obsession.

BMW’s comparable complex multi-link suspension only appeared in 1989 on the E31 coupe, and then on the “Seven” E38 and “Five” E39. But the M5 E34, even before the Mercedes 500 E was released, was standard equipped with rear shock absorbers featuring a hydraulic self-leveling mechanism to maintain constant wheel camber angles and clearance.

The battle started with marketing strategies, with BMW delving into detailed market share comparisons across various professions. The ‘Propeller’ brand resonated more with middle managers, while the ‘Star’ found favor among top executives and freelancers. BMW also boasted of engineering feats, claiming a significant aerodynamic improvement over its predecessor and achieving a drag coefficient of 0.30, while preserving the iconic negative slant of its nostrils. It subtly suggested that these results could have been even better, hinting that competitors like Mercedes used narrower tires to achieve optimal figures.

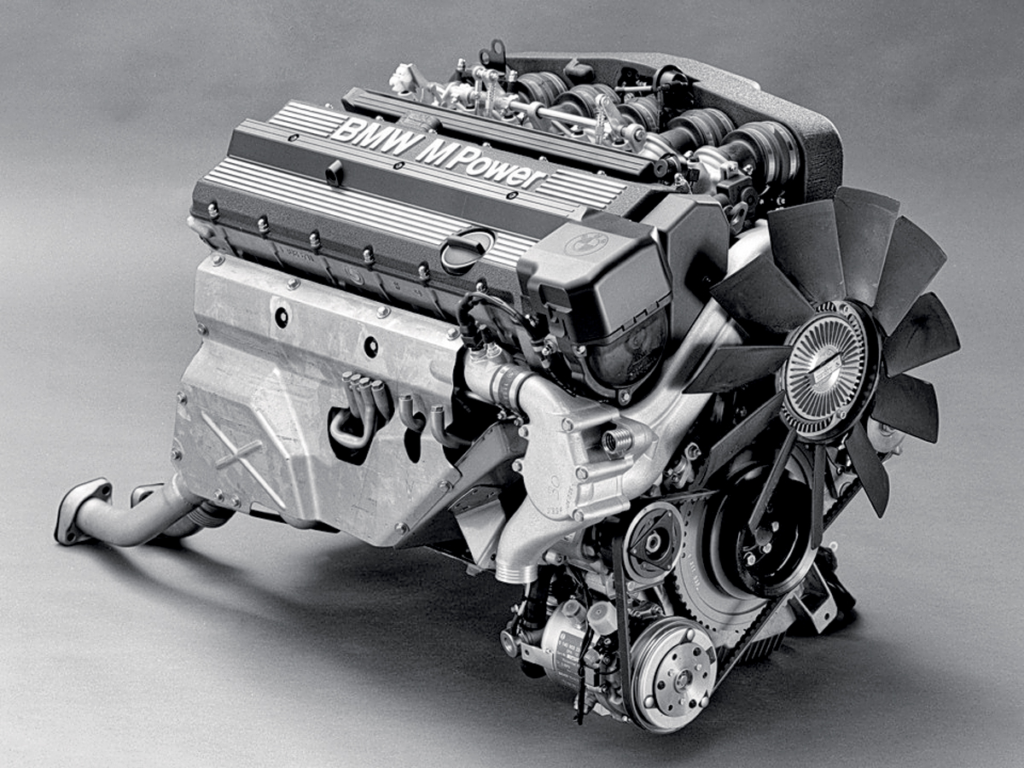

The lineage of M5 engines is traditionally traced back to the “six” M88 of the BMW M1, although the true progenitor was the BMW 3.0 CSL. The M88/3 version without a dry sump was allotted to the E28 M5 in Europe, while the first engine labeled S38B35 was its “catalytic” version for America. The S38 engines on the E34 inherited an iron block and a 24-valve DOHC head.

BMW matched Mercedes’s innovative windshield wiper system that cleaned 86% of the glass by extending their wipers’ reach and adding a mechanism at the base to enhance blade adherence at low speeds. They also introduced a unique feature where pulling and holding the door handle activates a lock heater, a clever addition for colder climates.

From the folding rear headrests operated by servos instead of springs, to a more sophisticated traction control system that managed both traction loss and sudden deceleration, BMW seemed determined not only to compete but to lead in innovation. Each model’s new features aimed to outdo the other, with BMW continually refining its designs to respond to Mercedes’s advancements.

The S38B36 engine (315 hp) of the pre-facelift M5 actually had a displacement of 3535 cc, but was designated 3.6 to differentiate it from the predecessor engine with a displacement of 3453 cc on the M5 E28.

Moreover, BMW’s catalog provided a rationale for the M5’s handling characteristics, indicating a deliberate tuning for neutral to slight understeer that could transition to oversteer when accelerating—perhaps a nod to the ‘drifty’ nature of the ‘124’.

This tit-for-tat rivalry not only pushed the boundaries of automotive technology but also highlighted the intense competitive spirit between the two brands. While the E34 briefly edged ahead of the W124, it fell short of replicating the ground-breaking impact of the twelve-cylinder E32. Despite sharing a platform with the ‘Seven’, the ‘Five’ was always in pursuit, adopting innovations like station wagon bodies, all-wheel drive, and enhanced safety features that echoed those pioneered by Mercedes. The BMW M5 remains a monument to this fierce rivalry, demonstrating how competition drives innovation and excellence in the automotive industry.

The Nürburgring effect means that during tests, the BMW M5 sedan with adaptive EDC shock absorbers completed a non-stop ten thousand kilometers on the Nürburgring’s “North Loop” and recorded the best time of 8’45.3″ (on a 20,832 km track).

Three years ago, to mark the 30th anniversary of the Mercedes 500 E, Porsche’s press service released an interview with Michael Hölscher, the project leader for the Typ 2758. Hölscher’s subsequent podcast appearances shed further light on the development nuances of this iconic model. He clarified that the sedan’s layout, the selection of the engine and transmission from the 500 SL roadster, along with its design and aerodynamics, were all determined exclusively by Mercedes. Porsche was primarily tasked with the integration of these components into the W124 chassis, which had not been initially designed to house V8 engines.

This collaboration required significant adaptations, including the relocation of intake ducts, the rerouting of brake and fuel lines, adjustments to the central tunnel, a widening of the track, and the conducting of a comprehensive driving test program. Interestingly, Mercedes opted not to include Nürburgring tuning in this project, underscoring a scenario where the client’s specifications were paramount for Porsche.

At the 1989 Geneva Motor Show, a convertible M5 with an E35 body was supposed to be shown, but a week before the premiere, BMW feared it would harm demand for the open M3 and canceled the project. The prototype was only unveiled in 2009.

A notable innovation from Zuffenhausen was the development of the electronic engine management system. Indeed, the 500 E was pioneering for both Mercedes and Porsche as it was the first vehicle equipped with a CAN-bus system.

Hölscher also debunked the myth that the 500 E couldn’t be accommodated on the Sindelfingen assembly line due to its excessively wide front fenders, which were rumored to have been designed by Porsche. He explained that these fenders were actually conceived by Mercedes designers, who were well aware of the constraints at the assembly line. The decision to not retrofit the Sindelfingen plant’s equipment for wider fenders but rather outsource certain production stages to Porsche was a cost-effective strategy. This raises an intriguing possibility: perhaps Mercedes intended for this special sedan to be assembled in a unique location, away from the standard production lines, much like BMW’s approach.

At the Porsche factory, Mercedes cars were assembled without a conveyor, on lifts, and carts. The VIN code of these cars should include the numbers 124.036.

Ultimately, the Mercedes 500 E was assembled across three locations. Stamped body panels were trucked from Sindelfingen to Zuffenhausen where Porsche added parts and assembled them into frames in the Reutter Bau building—named after the historic Reutter Karosseriewerk, a body shop that worked with Ferdinand Porsche from 1906 and played a significant role in early Porsche car bodies. After the initial assembly, the frames were returned to Sindelfinden for painting and then back to Zuffenhausen for final assembly in the Rössle Bau plant, previously home to the Porsche 959 production.

The early 90s, the finished products at the factory in Zuffenhausen: various Porsche 964s and forty Mercedes in the background.

The logistical complexity of this process was considerable; it took 18 days to manufacture each vehicle. Despite this, the production process proved to be more efficient than that of the BMW M5. Mercedes initially planned for Porsche to produce ten cars daily, but due to overwhelming demand, production rates doubled.

Priced higher than the S-class at 135,000 Deutsche Marks, with a peak in demand and production in 1992, the 500 E soon transitioned into the E 500 as part of the 1993 facelift that transformed the entire “124” series into the E-class. Although the engineering remained the same, the price increase to 146,000 Marks led to a decline in sales, culminating in the cessation of production in 1995. However, the less powerful 400 E (later E 420) continued until 1996 in double the numbers.

The 10,000th “Five-Hundred” Mercedes was produced in October 1994—already with the facelifted index E 500. After that, another 479 units were assembled. The car was gifted to Hans Herrmann, who raced for Mercedes in Formula 1 in the 50s, and in 1970 won the very first Le Mans for Porsche.

This project not only stabilized Porsche’s financial situation but also set the stage for future projects like the Audi RS2, where Porsche exerted a greater engineering influence. Michael Hölscher’s leadership extended beyond this project, contributing to the development of the Carrera GT and Porsche 918 Spyder before his retirement in 2016.

Mercedes, having recognized the lucrative nature of performance models through the 500 E project, decided in 1993 to keep this “caviar” of the auto business exclusive, leading to the release of the first Mercedes C 36 AMG and setting the stage for future high-performance innovations known well today.

Photo: BMW | Mercedes-Benz | Sergey Znaemsky

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: Эхо друг друга: как создавались BMW M5 и Mercedes-Benz 500 E из нашего ретротеста

Published June 20, 2024 • 12m to read