If you think this is a retro review, hold my beer. This is a story about a ten-year-long marriage. A relationship that began with love, descended into domestic routine, nearly ended in divorce, and eventually became a pragmatic union. It made the car better — and me more cynical. In short, this is what it’s like to live with a classic car in Russia.

I first met Andrey Sevastyanov — two-time Russian rally champion and head of the B-Tuning racing team — in the mid-2000s. In just a few years, he introduced me to everything I’d only read about in Autoreview as a kid: tuning, service, motorsport. And when I started thinking about buying my first car, Sevastyanov said, “You need something modern, safe, and reliable. Like a Ford Fusion.” So what did I do? I bought an Alfa Romeo 75 from the 1980s.

On the way home, the clutch died. Then the tow hook snapped. Then the headlight went out. When Sevastyanov saw it on his trailer, he sighed, “You’ve brought me everything I tried to protect you from — dim headlights, bald tires, unreliability, rust.” I just stood there, smiling like an idiot, completely in love.

Living with that Italian car nearly drove me mad, but it taught me the golden rule of old cars: the body must be solid. Interiors can be swapped, engines rebuilt, suspension overhauled. But if the sills buckle under a lift, you’ve already lost.

So when Alexey Zhutikov — whom you might know from automotive YouTube — and I decided in 2014 to buy a classic BMW 5 Series, our criteria were clear.

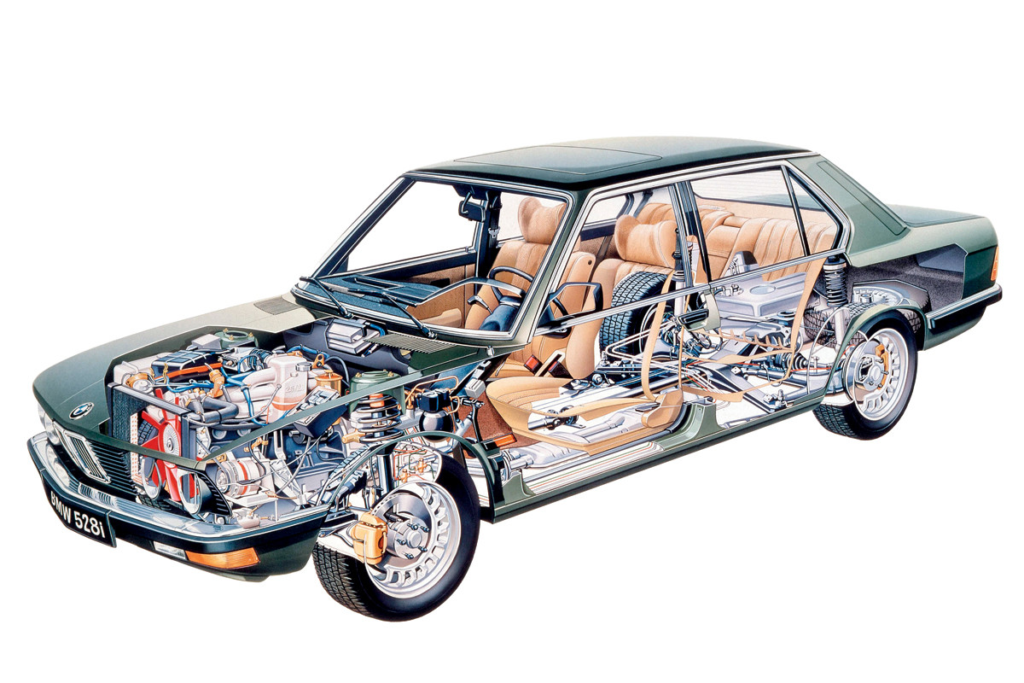

The BMW E28 “five” was produced from 1981 to 1988. Technically, it was a fairly moderate evolution of the previous E12 model: a 2625 mm wheelbase, McPherson struts at the front, semi-trailing arms at the rear, powerful versions were equipped with rear disc brakes (instead of drums) and a rear anti-roll bar (the front was installed as standard). For the first time, not only gasoline engines (1.8-3.5 l, 90-286 hp) were offered, but also a 2.4 diesel engine of its own design, and in naturally aspirated and turbocharged versions (86 and 116 hp, respectively). A total of 722 thousand cars were produced, all with a sedan body.

Why did we want one? Nobody knows. But we found a car with a great body. Yes, the engine was dead. The interior was incomplete. The paperwork was dodgy. But who cares when you’ve got a real Bavarian shark? One of those “project cars” you always see in classifieds.

We knew the road ahead would be rocky. But not this rocky. Our 1982 BMW 520i (E28 generation) was sent to the garage of another racing driver and motorsport master, Mikhail Zasadych. Over six months, it went from a lifeless shell to a functioning car.

Distant 2014. While Mikhail Zasadych tunes the engine, painters and fitters bring the body back to life

The engine was fully rebuilt and honed to tight tolerances — the crankshaft could be turned by hand. But the Bosch K-Jetronic mechanical fuel injection had a mind of its own, gulping down more than 20 liters per 100 km.

The body got new doors, a new hood, dent removal, and frame-straightening. We hadn’t noticed that the gaps between the rear doors and fenders were too small — a legacy of an old rear-end collision. Thankfully, it was straightened easily, and the whole body was resprayed in 1980s-style acrylic.

Only two liters, but six cylinders! When new, this M20 engine with mechanical injection K-Jetronic produced 125 hp and 165 Nm. How much it develops after rebuilding and switching to electronic injection Motronic, no one knows

We also replaced the suspension with H&R springs and Bilstein shocks. That turned out to be a mistake. The first of many.

At the time, spending 300,000 rubles on restoration felt outrageous. Ten years later, I realize Zasadych gave us an incredibly generous deal. But we were still far from perfection. The cosmetics, the interior, the mechanics (that fuel injection!) — all unfinished. Still, the car ran! For the first time since that snowy February day we’d paid 60,000 rubles for a Bavarian shark living in a snowbank.

Was it happiness? Not really. Like dating — when the initial rush fades and turns into a long grind, the magic disappears. After six months of garage visits and expenses, our passion dulled. The injection wasn’t tuned, the transmission wobbled, reverse didn’t engage well, and dozens of small issues spoiled the experience. The car moved, but evaluating any driving qualities was impossible. It wasn’t a car yet — just a promising project.

We tried another shop run by a friend. That was mistake number two. In an ideal world, friends keep promises. In the real one, friends put you off: “We’ll get to it after this customer.” Friends skip checks: “Let’s just get it done quickly.” That’s how our injection tuning went.

I remember that day as if it were yesterday. After leaving the service, the car drove three kilometers and stopped.

In the first attempt, the K-Jetronic flooded the crankcase with gasoline. The second attempt caused engine knock that destroyed the rebuilt block. The first replacement engine was left outside and rusted through. The second one was installed, and we ditched K-Jetronic for the newer Motronic system. But after welding the radiator support, they painted the front fenders and apron straight onto bare metal. Why bother doing it properly? We also replaced the entire brake system, lines included.

With classics and youngtimers, it’s rarely about “new” parts — it’s about finding different ones. OEM parts are insanely expensive, if you can even find them. Mostly you’re looking for rust-free doors, a dash where the clock still works, or trim that hasn’t lost its chrome. Every removed panel reveals three more problems. You start feeling like a character from Kafka’s The Castle, endlessly chasing some molding or door handle surround.

Two large saucers for the speedometer and tachometer, a central console facing the driver. This is a classic now, but the E28 generation was the first “five” with such an interior. This car has no airbags: the driver’s airbag was only installed on the E28 in 1985, and for a considerable surcharge of 2,310 marks.

That’s why most shops avoid working on classics. Too unpredictable. With a modern car, a mechanic knows how long it takes to change bushings and where to buy them. With a 40-year-old BMW, anything can happen, and cars often sit on lifts for weeks. For a shop, it’s lost profit at best, a loss at worst.

So one day, you find your car sitting dusty in a corner. It’s been there for a week. Parts weren’t ordered. Or the wrong ones were. And you’re switching garages again for the next season of Fix Me If You Can. My BMW 520i went through six.

Sometimes the E28 actually moved. Rare moments when I had time — and the car had the mood. Classic cars hate sitting. Fire them up every few months, and something always fails: dead battery, dry-rotted fuel lines spraying gasoline onto a hot block. Especially fun in winter. If you could bet on whether the car would start, the casino would always win.

The heater was overhauled several times

But the electric adjustment of the mirrors did not require intervention and still works

That’s why the successful drives were so precious. I forced myself to drive the BMW. To keep it healthy — and to fall in love with it. And, in time, that self-therapy worked. Maybe not love, but definitely fondness. That’s when I could finally see the 520i as a car — not just a decade-long project.

The most striking realization? Just how far automotive technology has come. It’s amazing. Based on my experience driving dozens of cars, I’d say cars became “modern” around the early 1990s. You don’t have to adapt to them. But a car from the ’70s? You sit down and immediately feel the era — tall trees, greener grass, and primitive machines.

The power steering is expectedly light, but “long”

The power steering? Its only job was to reduce effort. No feel, no precision. Same with the transmission — we replaced it, rebuilt it, and it’s still a relic. Sure, the shifter works. First and third never get confused. But compared to even a 1990s E36 320i, the five-speed Getrag in the E28 feels wooden and clunky. No finesse. No grace. Especially if you’ve ever driven a Mazda MX-5’s brilliant manual.

It turned out to be impossible to find the original cover, so we sewed it from scratch using patterns

It’s the same with everything. The clutch works, but harshly. The brakes are fine — just fine. And that’s the charm of a 40-year-old car! It pulls you out of the modern world, where cars are effortless. Behind the E28’s wheel, you don’t just drive — you command the car. A unique, vivid experience made stronger by its interior and exterior character.

The styling is its own reward. Officially designed by Claus Luthe, the E28 refined the ideas of Paul Bracq and Marcello Gandini, inherited from the earlier E12. Clean lines, perfect proportions, huge glass areas — not a gram of excess. Park an E28 next to today’s cars and it looks like Audrey Hepburn in a room full of clowns. No fake vents, no useless creases. That elegance forgives a lot. But not the suspension.

The olive interior goes well with the rich green body. By today’s standards, these seats are so-so

Zasadych’s idea was logical: if you’re rebuilding the chassis, why not make it tighter, more planted? We trusted H&R and Bilstein. What we didn’t consider was the roads. On a track, sure, this setup would improve handling. But on Russian roads? The springs and shocks were stiffer than the body. Every bump first hit the suspension, then rattled through the car — and your spine. Useless behavior that made the car feel worse, not better.

There is little more space in the back row than in modern 3-series cars. Manual windows were the norm in BMWs in the 1980s.

At first, I endured it. Then I reverted to the stock suspension after just one long trip. And you wouldn’t believe the transformation. Soft, smooth, composed — exactly how a classic should feel. Trying to make it a race car is like asking your grandpa to run the 100m at the Olympics.

But even with the softer suspension, the BMW mostly stayed parked. A few outings per season. You know what happens when old cars sit. So I decided to sell it.

Winter 2020, BMW still with “sport” suspension and non-original BBS-Mahle wheels. At the time, it seemed like a great solution

Was it hard? Of course. But the alternative was paying for parking, insurance, maintenance — and hunting rare parts — for a car I barely drove. Selling seemed like the only smart move.

Only… nobody bought it.

Some just wanted a free test drive. They’d gush over the condition, shower me with compliments, promise to return — and never did. Maybe I was too honest. Maybe 350,000 rubles sounded like too much — even though I’d put over a million into it over the years (I stopped counting). Sure, a lot of that money went into fixing other people’s mistakes. But still — I stopped being a seller and became a monkey with a camera. So I gave up.

Then someone I knew asked to borrow it. They returned it with a giant grin.

No matter how we soldered the dashboard, we couldn’t defeat the Inspection alarm light

Eureka.

To me, this green BMW had become a tale of wasted time and money. But to others, it was a ticket to a theme park — a train to Platform 9¾. I casually posted it for rent on social media. And boom.

During the May holidays in 2021, renters drove the car more than I had in years. Then I remembered I also had a Cadillac Fleetwood and a BMW E36 320i. My friends had unused classics too. That’s how Autobnb was born — a vintage car rental service for those who see cars as more than transport. My E28 was the beta — the car that started it all.

In three years, the E28 racked up 30,000 km. But how much it’s driven in 40 years? Who knows. Who cares. Three engines, two gearboxes, new suspension, new brakes — odometer numbers mean nothing. Especially since two out of three dashboards didn’t even have working odometers.

That once-finicky BMW now tours Russia’s Golden Ring, competes in rallies, stars in commercials, and brings joy to dozens of people. The 520i is living its best life.

BMW has often been filmed in various unusual projects. Here it was lightened as much as possible to show the best lap time

It needed that shake-up. That regular use. Yes, new problems appeared: the rear bumper mount rusted off (we welded it), the exhaust started rattling (we fixed it), the audio system died (we replaced the speakers). But breakdowns per kilometer have dropped dramatically. Only one time did it fail completely — a coolant hose popped off.

Miracle? Magic? Holy water through a TV screen? Almost. Because nothing lasts forever. After the 2023 season, we sent it for diagnostics. The bill was sobering. It felt like the car’s restoration buffer was finally used up.

Lightness, elegance and conciseness. For this design I am ready to forgive the “five” almost everything

New power steering reservoir, filters, fuel pressure regulator, spark plugs, fuel pump, front control arms, injectors — and a bunch of other items. Including fuel tank work. It cost several hundred thousand rubles. Was it a lot? Yes. Expected? Also yes. And worth it? Absolutely. Because those three years of joy had paid it all back.

Before writing this, I took the E28 out for a drive — for the first time in a year. A summer evening. Empty road. Windows down. The warm glow of halogen headlights. Just me and the car, reminiscing about the last decade. Pure bliss.

I even believed — for a moment — that the M20B20 inline-six really was making 125 horsepower and 165 Nm. At least, cruising at 110 km/h felt easy. The pleasant pull past 3,000 rpm made me delay every shift.

But one evening was enough. As crude as it sounds, a one-night stand is the perfect format for this car. Anything more — and we’d fall back into domestic boredom. Which usually ends in divorce. And I don’t want that.

Rustam Akiniyazov instead of an afterword

From the very beginning, her name was obvious: Bertha.

When Nikita suggested we take the 40-year-old German beauty to the seaside, it sounded amazing. Driving to the beach with the windows down, turning heads — priceless. The 2,000-km road trip was daunting, but hey — I once drove to Crimea as a student in a Lada. Even rebuilt the engine in Millerovo. The mechanic let us use the garage and tools. Life teaches you things. Maybe my hands still remember.

This time, we made it — no breakdowns! But not without issues. On the highway, it was clear: the injection was running rich (confirmed by the 20L/100km fuel consumption and the smell of gasoline). Worse, exhaust fumes were leaking into the cabin — dangerously.

We couldn’t figure out how. But the paradox was real: the faster we went, the worse it smelled. So we opened all the windows. Plenty of air — and carbon monoxide.

At the destination, we found the cause. The trunk gasket was missing — the service shop either forgot or didn’t find a replacement. At speed, the negative pressure behind the car sucked exhaust straight into the trunk — and then the cabin. A trunk seal from a Lada 21099 fixed it completely.

And from that day forward, her full name became:

Bertha Nikitishna Gassenwagen.

Photo: Alexey Zhutikov | Efim Gantmakher | Ilya Agafin | BMW | Nikita Sitnikov

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: BMW E28: жизнь с олдтаймером в российской действительности

Published June 26, 2025 • 12m to read