Mali stands at the heart of West Africa’s history and culture. It was once home to great empires that influenced trade, learning, and art across the region. The country’s heritage is visible in its ancient cities, mud-brick mosques, and manuscripts that reflect centuries of scholarship. The Niger River remains central to life, linking farming villages, markets, and historic towns along its path.

Visitors who come to Mali can explore places like Djenné, known for its grand mosque and traditional architecture, or Timbuktu, once a center of learning and trade across the Sahara. Music, storytelling, and craftsmanship continue to play an important role in local life. Though travel requires preparation and care, Mali offers deep insight into West Africa’s cultural roots and enduring traditions.

Best Cities in Mali

Bamako

Bamako is Mali’s main political and cultural center, situated along the Niger River and structured around busy markets, administrative districts, and riverfront activity. The National Museum of Mali offers one of the region’s most detailed introductions to Malian history, with collections of archaeological material, masks, textiles, and musical instruments that outline the diversity of the country’s ethnic groups. Nearby, markets such as Marché de Médina-Coura and the Grand Marché bring together artisans, traders, and agricultural producers, giving visitors a direct look at regional commerce and craft traditions.

Music remains a defining feature of the city. Griots, singers, and instrumentalists perform in neighborhood venues, cultural centers, and open-air clubs, reflecting long-standing oral traditions and modern musical developments. Because of its central location and transport links, Bamako also serves as a starting point for travel to southern Mali’s towns, rural areas, and the river regions toward Ségou and Mopti.

Djenné

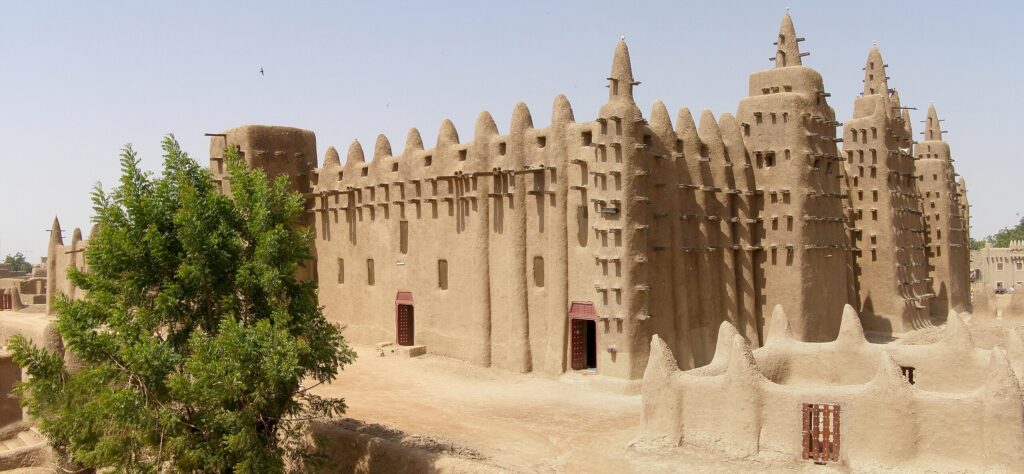

Djenné is one of Mali’s oldest urban centers and a key example of Sudano-Sahelian earthen architecture. Its focal point is the Great Mosque of Djenné, recognized as the world’s largest mud-brick building and maintained through an annual community event known as the Crépissage. During this process, residents apply fresh mud plaster to protect the structure from seasonal weather, offering a rare instance of monumental architecture preserved through ongoing local practice. Visiting the mosque and the surrounding square provides clear insight into how Djenné’s built environment has been sustained for centuries.

The town is also known for its weekly market, which draws traders and farmers from surrounding villages. The market occupies the central square and creates a temporary hub of regional exchange, with stalls selling textiles, livestock, food staples, and handmade goods. Walking through the narrow streets of Djenné reveals traditional adobe houses, neighborhood courtyards, and small workshops that illustrate long-standing patterns of urban life along the inland delta. Djenné is typically reached by road from Mopti or Ségou and is included in itineraries focused on historic towns

Timbuktu

Timbuktu developed as a major center of Islamic scholarship and a key node on trans-Saharan trade routes linking West Africa with North Africa and the Middle East. The city’s historic mosques – Sankore, Djinguereber, and Sidi Yahya – represent the core institutions around which teaching and manuscript production once flourished. Although some structures have been restored, their form still reflects the architectural principles of the Sahel and the organizational layout of the old scholarly quarters. Manuscript libraries maintained by local families preserve texts on astronomy, mathematics, jurisprudence, medicine, and poetry, offering evidence of the city’s intellectual networks over several centuries.

Access to Timbuktu is limited and requires careful planning because of security conditions in northern Mali. Travel typically involves coordination with local authorities, charter flights, or supervised overland routes. Visitors who reach the city usually combine mosque visits with meetings at manuscript preservation centers to understand the transmission of knowledge and the role of family custodians.

Mopti

Mopti sits at the confluence of the Niger and Bani rivers and functions as a major commercial hub for central Mali. Its port area is central to daily activity, with boats transporting goods and passengers through the Niger Inland Delta. The Great Mosque of Mopti, built in the Sudano-Sahelian style, anchors the old quarter and reflects the city’s long connection to river-based trade and Islamic scholarship. Surrounding markets offer fish from the delta, salt from the north, textiles, leatherwork, and handicrafts produced by different ethnic groups in the region.

Because of its position between the inland delta, Dogon Country, and northern transport routes, Mopti often serves as a staging point for travel deeper into Mali. River excursions on pinasses (traditional wooden boats) provide access to delta villages and seasonal wetlands, while road journeys connect Mopti to Bandiagara, Sévaré, and other inland towns.

Best Historical and Archaeological Sites

Great Mosque of Djenné

The Great Mosque of Djenné is the most prominent example of Sudano-Sahelian mud-brick architecture and a central landmark of the town. Built from sun-dried adobe, wooden beams, and plaster, the structure requires regular maintenance to withstand seasonal rain. This need for upkeep has led to the annual Crépissage, a community-led festival during which residents prepare and apply fresh mud to reinforce the walls. The event demonstrates how architectural preservation in Djenné relies on collective effort rather than external intervention.

The mosque stands beside the town’s main square, making it a focal point for both religious life and weekly trade. Although access to the interior is restricted to Muslims, visitors can observe the exterior details from multiple angles and learn about construction techniques from local guides. The site’s UNESCO designation highlights its significance as an enduring example of earthen architecture and a living tradition of community maintenance. Travelers typically visit the mosque as part of broader itineraries exploring Djenné’s historic neighborhoods and the Niger Inland Delta region.

Tomb of Askia (Gao)

The Tomb of Askia in Gao was constructed in the late 15th century under Askia Mohammad I, reflecting the consolidation of the Songhai Empire and the increasing role of Islam in political and social life. The structure’s pyramidal form, reinforced by projecting wooden beams, follows architectural principles common to the Sahel and served as both a burial place and a symbol of authority. The surrounding complex includes a mosque and prayer spaces that have been expanded or adjusted over time, illustrating how the site remained active within the community.

Located near the Niger River, the tomb has long functioned as a landmark for Gao and the wider region. Its UNESCO World Heritage status recognizes both its architectural importance and its connection to the historical development of West African empires.

Ancient Trade Routes & Caravan Towns

Across Mali, the remains of former caravan towns illustrate how trade networks once connected the Niger River region with North Africa and the wider Sahara. These routes moved gold, salt, leather goods, manuscripts, and agricultural products, supporting large empires such as Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. Settlements along the caravan corridors developed mosques, manuscript libraries, storage compounds, and markets that served traders arriving from different regions. Even today, town layouts, family lineages, and local customs reflect the influence of these long-distance exchanges.

Many caravan-era towns retain architectural elements shaped by trans-Saharan commerce – earthen mosques, fortified granaries, adobe houses with internal courtyards, and streets oriented to accommodate pack animals. Travelers exploring Mali’s historic centers – such as Timbuktu, Gao, Djenné, or towns around the inland delta – can trace how trade routes influenced religious scholarship, political authority, and urban growth.

Best Natural and Cultural Landscapes

Dogon Country

Dogon Country extends along the Bandiagara Escarpment, a long line of cliffs and plateaus where villages are built at the top, base, or on the slopes of the rock face. The region contains ancient cave dwellings attributed to earlier populations and granaries, houses, and meeting structures constructed from stone and mud. This layout reflects Dogon social organization, land use, and long-term adaptation to the environment. Walking routes between villages demonstrate how footpaths connect settlements used for farming, local trade, and community gatherings.

Trekking itineraries typically include villages such as Sangha, Banani, and Endé. Local guides explain Dogon cosmology, the role of masks in ceremony, and how shrines and communal buildings fit into village life. Distances and terrain allow for both short visits and multi-day routes. Access is usually arranged from Sévaré or Bandiagara, and conditions require advance planning.

Niger River & Inland Delta

The Niger River forms the backbone of Mali’s economy and settlement patterns, supporting agriculture, fishing, and transport across much of the country. Between Ségou and Mopti, the river widens into the Inland Delta, a seasonal floodplain where water spreads into channels, lakes, and wetlands. During the flood season, communities adjust their activities—farmers plant along retreating waterlines, herders move livestock to higher ground, and fishermen travel through temporary waterways to reach productive fishing areas. The region’s cycles shape trade, food supply, and local migration.

Boat journeys on the Niger offer direct views of this river-based way of life. Travelers see fishing crews casting nets, riverbank villages built from mud-brick, and pirogues transporting goods to market towns. Some itineraries include stops at small settlements where visitors can learn about rice cultivation, pottery making, or the use of the river for daily household needs. Access points for river trips are typically in Ségou, Mopti, or villages along the delta’s edge.

Sahel & Southern Savannas

Mali’s landscape shifts gradually from the dry Sahel in the north to more humid savannas in the south, creating a range of environments that support different forms of agriculture and settlement. In the Sahel, communities organize farming and herding around short rainy seasons, relying on millet, sorghum, and livestock as the main sources of livelihood. Villages built from mud-brick structures are positioned near wells or seasonal streams, and baobab trees mark communal areas and farmland boundaries. As the terrain becomes greener toward the south, fields expand to include maize, rice, and root crops, and river systems support fishing and irrigation. Many cultural festivals and community events follow the agricultural calendar. Ceremonies may mark the start of planting, the arrival of the rains, or the end of the harvest. These gatherings often include music, storytelling, and masked performances that reinforce social ties and local identity.

Best Desert Destinations

Sahara Fringe & Northern Mali

Northern Mali marks the transition from the Sahel into the wider Sahara, where dunes, gravel plains, and rocky plateaus extend for hundreds of kilometers. This environment shaped the development of trans-Saharan trade routes used by Tuareg caravans to move salt, grain, livestock, and manufactured goods between West Africa and North Africa. Settlements along these routes often grew around wells, oasis gardens, and seasonal grazing areas, serving as rest points for traders and pastoral communities. Remains of caravan tracks and encampments still exist across the region, illustrating how mobility and resource management structured life in the desert.

Travel in northern Mali requires careful planning due to distances, climate, and security conditions, but historically significant locations such as Araouane and the salt mines of Taoudenni highlight the long-standing economic connections between the Sahara and the Niger Valley. These routes once linked cities like Timbuktu and Gao to coastal markets through large-scale camel caravans.

Tuareg Cultural Regions

Tuareg cultural regions stretch across northern Mali and adjoining parts of the Sahara, where communities maintain traditions rooted in pastoralism, metalwork, and oral history. Social life is organized around extended family networks and seasonal movement between grazing areas, with camps and settlements positioned according to water availability and herd management. Silver jewelry, leatherwork, saddles, and metal tools are produced using techniques passed down through generations, and these crafts remain a central part of Tuareg economic and ceremonial life. Music and poetry – often performed with string instruments such as the tehardent – convey themes of travel, lineage, and landscape, forming a distinct cultural expression known internationally through modern desert blues.

Tuareg influence is important for understanding Mali’s broader cultural identity, especially in regions connected historically to trans-Saharan trade. Their role in guiding caravans, managing oasis resources, and transmitting knowledge of desert routes shaped interaction between the Sahel and North Africa. Visitors who engage with Tuareg communities, whether in urban centers like Gao and Timbuktu or in rural areas of the Sahara fringe, gain insight into how nomadic traditions adapt to contemporary economic and environmental pressures.

Hidden Gems in Mali

Ségou

Ségou is located on the Niger River and served as the political center of the Bambara Empire before the colonial period. The town’s riverside layout reflects its long-standing role in agriculture, fishing, and river transport. Walking along the riverfront takes visitors past colonial-era buildings, administrative structures, and small ports where boats still move goods and passengers between settlements. Ségou is also known for its craft traditions. Pottery workshops operate in and around the town, showing how clay is collected, shaped, and fired using methods that have been practiced for generations. Textile dyeing centers, especially those that use fermented mud-dye techniques, provide further insight into local craft economies.

The town hosts several cultural events throughout the year, drawing musicians, artisans, and performers from across Mali. These gatherings highlight the region’s artistic heritage and its connections to surrounding rural communities. Ségou is reached by road from Bamako and often serves as a starting point for river trips toward Mopti or for visits to villages along the Inland Delta.

San

San is a central Malian town known for its importance to Bobo and Minianka communities, whose spiritual practices and social structures shape much of the region’s cultural life. The town contains shrines, meeting houses, and communal spaces used during ritual events, while local workshops produce masks, instruments, and ceremonial objects tied to longstanding animist traditions. Mask performances, when held, mark agricultural cycles, rites of passage, or community agreements, and local guides can explain the symbolism and social roles involved.

San is located on major road routes between Ségou, Mopti, and Sikasso, making it a practical stop for travelers moving between southern and central Mali. Visits often include walks through artisan quarters, discussions with community representatives, or short excursions to nearby villages where farming, weaving, and ritual practices remain closely linked to seasonal rhythms.

Kayes

Kayes is located in western Mali near the Senegalese border and developed as an early hub of the Dakar–Niger railway. The town’s layout and remaining railway structures reflect this period of transport expansion, which connected interior regions with coastal markets. Walking through Kayes reveals administrative buildings, markets, and residential quarters shaped by the town’s role as a commercial gateway between Mali and Senegal. The surrounding area is characterized by rocky hills and river valleys that contrast with the open Sahel farther east.

Several natural sites lie within reach of the town. The Gouina and Félou waterfalls on the Sénégal River are popular stops, accessible by road and often visited during the dry season when river levels allow for clearer views of the cascades. Small villages near the falls offer insight into local farming and fishing practices. Kayes is connected to Bamako and regional centers by road and rail, making it a practical entry or exit point for overland travel.

Kita

Kita is a regional center in southern Mali, surrounded by farmland and low hills that support cotton, millet, and vegetable cultivation. The town functions as a trading point for surrounding villages, with markets where local produce, textiles, and handmade goods are exchanged. Walking through Kita provides a straightforward look at rural commercial life, including small workshops where instruments, tools, and everyday household items are produced.

Kita is also recognized for its music traditions, which remain active in community gatherings, ceremonies, and local festivals. Travelers can meet musicians or observe rehearsals and performances that reflect cultural practices of the Mandé region. The town lies on road routes connecting Bamako with western Mali, making it a convenient stop for those traveling between the capital and Kayes or the Senegalese border.

Travel Tips for Mali

Travel Insurance & Safety

Comprehensive travel insurance is essential for visiting Mali. Make sure your policy includes medical evacuation coverage, as healthcare facilities are limited and distances between major towns can be long. Insurance that covers trip cancellations or unexpected changes is also advisable, given the potential for regional travel disruptions.

Conditions in Mali can change, so travelers should always check updated travel advisories before planning or undertaking their trip. A yellow fever vaccination is required for entry, and malaria prophylaxis is strongly recommended. It’s also important to use bottled or filtered water for drinking and to maintain good sun protection and hydration, especially in arid regions. While parts of the country remain stable, others may have restricted access; traveling with local guides or through organized tours is the safest approach.

Transportation & Driving

Domestic flights are limited, and most travel within Mali relies on buses and shared taxis that connect major towns and regional centers. During the high-water season, river transport along the Niger provides a scenic and culturally rich way to move between cities such as Mopti and Timbuktu.

Driving in Mali is on the right-hand side of the road. Road conditions vary significantly – while main routes between large towns are generally serviceable, rural roads are often unpaved and require a 4×4 vehicle, particularly during or after the rainy season. Travelers who plan to drive should carry an International Driving Permit along with their national license, and be prepared for police checkpoints on major routes. Patience and local knowledge are key to safe and enjoyable travel across the country.

Published December 21, 2025 • 15m to read