In an iconic BMW TV commercial, a jet-powered car races across a dried salt lake, slicing through the air, kicking up clouds of dust, and nearing a speed record. Suddenly, the pilot deploys a braking parachute, the car halts, and the sound of a door opening fills the air—a person in a jumpsuit appears on the screen, peering straight at us to check the camera lens. It turns out the entire race was captured through the “eyes” of a BMW M5 sedan, with a camera mounted on its door.

This is a classic advertising gimmick, but it truthfully conveys that the most intriguing vehicles in movies often remain behind the scenes. Among them are those engineered in Russia.

I encountered this technology under similar circumstances. Last summer, I had the opportunity to ride in the track prototype Rossa—the same one that racer Roman Rusinov plans to produce. It features ten cylinders, 680 horsepower, and an acre of carbon fiber. Yet, the vehicle that arrived to film this car in action was an even more formidable beast.

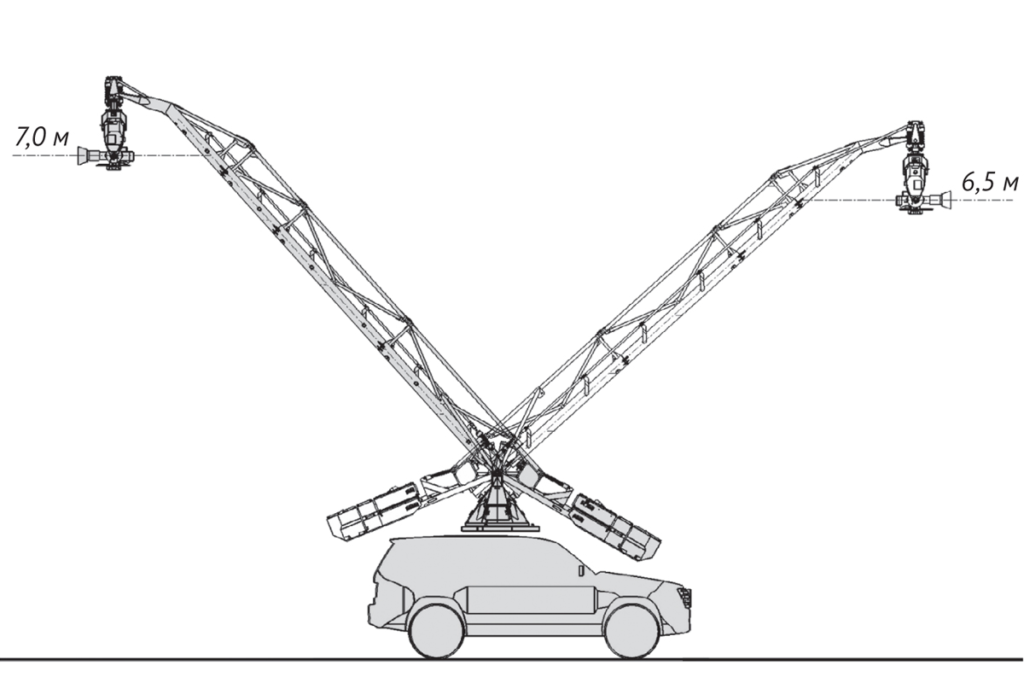

For most of its life, it was a 2010 Mercedes-Benz ML 63 AMG from the W164 series, residing with a Moscow dentist’s family. However, a couple of years ago, it fell into the hands of filmmakers and underwent a transformation worthy of Mad Max. Its body swapped metallic paint for matte film, bristled with wires and brackets, and a tower with a boom sprouted from its roof. This is the Russian Arm. Although the cladding reads “Performance Filmworks Edge Crane,” in the film industry, the term “Russian arm” refers to all automotive camera cranes with a stabilized camera, akin to how “Xerox” became synonymous with photocopying.

The “Russian Arm” is the king of the film set. Its cost rivals that of many supercars, with setups priced up to a million dollars, and daily operation costs running into the hundreds of thousands of rubles. What’s especially impressive is the scene before shooting begins: three people climb into the car’s cabin, with another two entering the trunk, each with a distinct mission.

The Mercedes ignites, catches up with the hero car, and begins to dance around it. They draw closer, drift apart, swap places, and sometimes charge towards each other. The magic of the crane ensures that the camera at the end of the boom maintains the frame, keeping its position regardless of the movements of the Mercedes carrying it. Not even sways, bumps, accelerations, or the absence of asphalt affect the shoot; the crane can easily traverse the roadside, and the camera’s position remains steady.

That day sparked the idea to persuade the crane driver to swap roles, making this remarkable vehicle the main character of the test.

However, there are other types of operator vehicles, not necessarily equipped with a tower. Camera cars with stabilized suspensions, such as “steadicams,” are also successfully employed on sets. They are much simpler and cheaper but can produce nearly the same effect. Or can they? At the end of last year, I invited both the Edge Crane based on a Mercedes and a more modest operator’s Volvo XC90 V8 to the testing ground.

The Hand of Tula

Form follows function, but in the case of a film crane, its function dictates not only its appearance but also the choice of the brand, model, and configuration of the carrier vehicle. A search for “Russian arm crane” mostly returns images of vehicles based on Mercedes ML and Porsche Cayenne models from various generations, often even the very first, still frame-based M-Class.

For a crane, essentials include a robust body, spacious cabin, durable suspension, and powerful engine. Precise traction control and handling are also crucial. That’s why the old AMG versions of the W164 generation seem almost tailor-made for this role. The 2010 model year was the last for the ML 63 AMG with the naturally aspirated 6.2-liter M156 V8 engine before the subsequent W166 generation switched to turbocharged engines.

This Mercedes underwent no special modifications to its engine and transmission. It traveled 150,000 kilometers “in peace” without serious issues—and just as effortlessly clocked another 20,000 kilometers after being repurposed. However, it seems not a single element of the body remains in its original form.

Rule number one: a vehicle with a crane should not reflect in the hero car or cast glare or shadows on it. Hence, instead of factory paint, a matte film is used. For the same reason, the rear lights and brake signals are made switchable.

Rule number two: the crane vehicle should not kick up dust, throw mud, lift snow, or emit exhaust into the frame. Therefore, in addition to wide mudguards under the rear bumper, a solid “full-length” skirt is installed.

Rule number three: the boom and tower must be easily accessible. Thus, the hood is reinforced with duralumin sheets to support a standing person, and steps are installed on the sides of the body.

Rule number four: the crane must be lightweight, strong, dismountable, and compact. For long-distance moves, the boom and all accessories must be disassembled by a three-person team in one day and packed into five containers. Assembly should also take just one day.

Rule number five: the crane must not carry unnecessary weight. Every kilogram on the roof raises the center of gravity, impairs handling, and increases body roll. Therefore, batteries and power units are installed in the cabin behind the rear bench, with numerous signal and power cables running to the roof through a hole in the body pillar.

Rule number six: there is no time to charge the crane’s batteries on set, so they are continuously recharged from the standard car alternator through special power units that convert 12 V to the 70 V required by the crane.

Rule number seven: a vehicle with a crane should have a large trunk from which the crane operator and focus puller can work. Therefore, instead of a floor panel and spare tire, a U-shaped bench is installed in the trunk area.

Overall, the cabin’s equipment would outmatch any Chinese electric vehicle: six monitors. Plus, two remote controls with joysticks. And this is practically the most basic configuration.

Behind the driver almost always sits the operator who controls the camera. The rest of the crew may swap places. The team must include a crane operator who manages the boom’s vertical movement and azimuth rotation (clockwise and counter-clockwise), a focus puller (focus assistant), and a director or assistant director.

The boom reads “Edge Crane”—the brand of the California-based company Performance Filmworks, which provides film cranes for various shoots and handles the development, modernization, and testing of such equipment and its accessories. However, this crane was actually built by the Russian firm Leskov from Tula, the primary engineering and manufacturing partner for Performance Filmworks. Although there are few Russian components, aside from the structural elements, the basic underlying principles that govern the crane’s operations are of domestic origin.

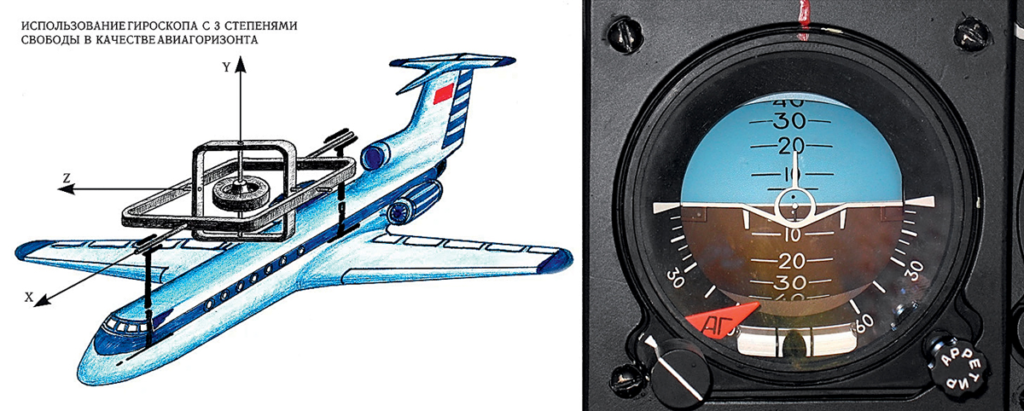

The story of the Russian Arm phenomenon deserves its own chapter—look for it in the historical section. For now, just remember that this crane operates based on gyroscopic indicator stabilizers. The theory and practice of their application in the film industry were developed by the staff of the Bauman Moscow State Technical University. It all began in the late ’70s at the department of gyroscopes and gyroscopic systems at the faculty of instrumentation engineering.

In the late ’90s, the technology gained recognition in Hollywood and by the mid-2000s had spawned so many analogs that the term Russian Arm became a generic name for any remotely controlled operator cranes mounted on a car roof. Today, the key developer, a former Bauman student, lives in the USA and is the chief engineer at Performance Filmworks. In Russia, Leskov handles the engineering, production of these cranes, and occasionally, the modification of vehicles.

So what’s really inside?

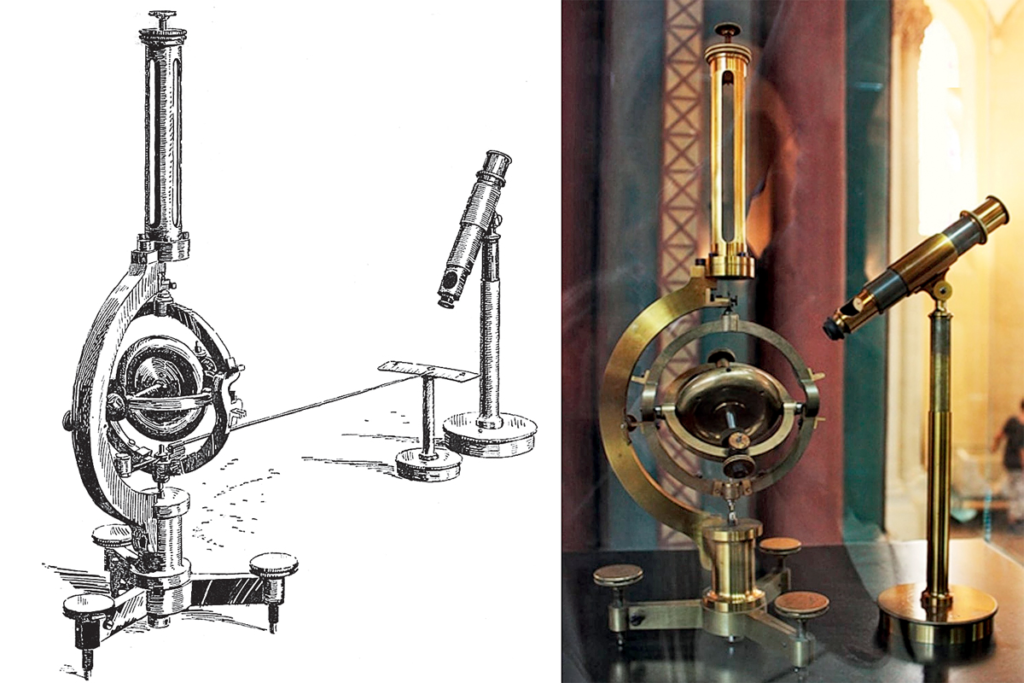

To understand, let’s start with what a gyrostabilizer is. It’s a device that operates on the principle of a gyroscope, that is, a spinning top. A rotor spun up to very high speeds tends to maintain its original orientation in space. The higher the speed of rotation, the greater the restoring torque to its original position. If such a top is placed in a frame with gimbals along all three axes, it forms a gimbal suspension where the rotor has complete freedom to maintain its original orientation.

If an arrow were attached to the inner frame of the gyroscope, it would make the simplest device with which the French physicist Jean Bernard Léon Foucault demonstrated Earth’s rotation 172 years ago. Later, the rotor was connected via rods to the steering mechanism, creating a gyrostabilizer that began being used on torpedoes by the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century, gyroscopes became a crucial component in navigation and orientation systems for the vast majority of transport vehicles, including rockets.

However, gyroscopes with rotating rotors are heavy, large, fairly noisy, and not always reliable. They require a drive to maintain rotation at tens of thousands of revolutions per minute and time to spin up. That’s why, since the mid-’90s, fiber-optic or vibrating gyroscopes have been used in camera stabilizers. The former are electronic sensors that measure angular velocity based on the time difference it takes for a light pulse to travel through a fiber optic coil. The latter do the same based on changes in the direction of their vibrations. Vibrating gyroscopes are modern angular velocity sensors used everywhere from hoverboards to smartphones.

They are also installed in the stabilizers of the Edge film crane. Besides them, there are tachometers, encoders, accelerometers, Hall effect sensors, potentiometers, measurement module assemblies with special calculation algorithms, and other sensitive elements. Based on signals from all sensors, a feedback loop is constructed, allowing special drives to compensate for vibrations, swaying, rolls, impacts, and other harmful effects.

Modern electronic filling significantly saves weight, but still, when we put the crane on the scales, it showed 2813 kg! A half-ton heavier than the factory’s equipped mass and right up to the allowed total. Such additional weight could not but affect dynamics, so the best result in acceleration to 100 km/h was almost two seconds worse than the factory figure: 6.8 s instead of 5.0 s. But is it just for seconds that we love the old naturally aspirated AMG?

The charisma of the engine remains with it one hundred percent. It’s an engine that makes you smile with pleasure. The throttle connection is flawless, the pull is stunning, and the sound unforgettable. The 6.2-liter “eight” easily revs up to 7000 rpm, but it has an even more important quality: even mundane trips at half throttle are filled with joy from interacting with a true big engine.

In addition, the 7G-Tronic “automatic” works perfectly here. In this generation, it already knows how to shift down three gears at once, so the Mercedes can almost instantly switch from calm driving to sharp acceleration. Simply put, this power unit knows how to do everything.

It’s so good that I even started to recall if there was any large seven-seater Mercedes with such an engine. And there was—the R 63 AMG. Also 510 horsepower, the same “automatic,” plus a family-friendly cabin. I’ll remember this thought.

Besides the engine, the ML 63 AMG captivates with a noble steering feel. It is sufficiently lengthy, a bit more than three full turns from lock to lock, but not at all lazy. Without unnecessary heaviness and sharpness, yet with rich feedback and a clearly defined center. Responses are quick and precise. An exemplary vehicle. But what would happen if we imagined that we were filming a chase and had to drive flat out?

“I’m not going to do a reshoot with this,” said Yaroslav Tsyplyankov, as soon as he saw the film crane. To be fair, it should be noted that emergency maneuvers were not part of the test program from the beginning because they can only be done with the tower turned on, that is, with almost the full crew in the cabin and the boom operator adjusting its position with every maneuver. Otherwise, what Yaroslav immediately guessed would happen. And with the tower turned off, sharp maneuvers should not be done also because there is a risk of damaging the mechanisms.

However, it is felt that three and a half tons above the roof increased body roll and the suspension struggles with such a load. Pneumatic struts are needed for such vehicles so that the body does not sag under the weight of the crane, but here the airbags are already working at their limit. Regardless of the selected shock absorber mode, the Mercedes rides hard and lets in bumps from roughness, even on thicker 275/55 R20 tires than prescribed by the manufacturer. However, it was hard to expect otherwise, as during operation the Mercedes drives with a full crew, adding about another 400 kg on top. And the process doesn’t always involve driving on asphalt: the AMG suspension wasn’t prepared for that.

So, the next plans for this Mercedes include replacing the airbags and installing even plumper 275/65 R18 tires to work more on rough terrain. Plus another specific upgrade—reprogramming the ESP to bypass the lock of driving with two pedals. This is necessary for perfect control of the vehicle when filming at a short distance, and the standard setting does not allow this.

A few days after the tests at the track, I had the opportunity to observe this crane in action on a real shoot. The technical task was very simple—moving the vehicle through regular streets from different angles—yet the process took almost half a day. Time goes into assembling the equipment and perfectionist execution of each frame. In short, the film crane does not simplify the work, on the contrary. But the reward is the quality of the picture. However, there are alternatives.

To check this, I borrowed my friend-operator’s car for one day, with whom we regularly work on different shoots. It was a 2006 Volvo XC90 V8 with a custom-built manipulator.

Swedish Tail

The initial requirements for the vehicle were very similar: a large, spacious crossover with a powerful engine. However, the concept of filming equipment here is radically different. A powerful vertical bar is mounted firmly between the roof rails and the towing loop. A mechanical pantograph-suspension is just as rigidly attached to it. By appearance, it resembles an “arm” more than the Russian Arm, but in terms of capabilities, it’s a relatively simple “steadicam.” Here, only parallelograms, springs, and dampers are involved. There’s no stabilization, and no active mobility, but it dampens vibration well, albeit only in the vertical plane. However, another part of the system does the main work.

A DJI Ronin 2 stabilizer is mounted at the end of this “arm”—it includes gyroscopes, joints, and servo motors. This operator’s suspension has mobility and stabilization across three axes. That means the operator can tilt the camera forward and back, lean it right and left, and pan 360 degrees around the vertical axis. But to change the perspective—for example, to move the camera higher or farther from the body—you’ll need to stop and pick up a wrench.

But such a tail is hundreds of times cheaper and tens of times lighter than the “Russian arm.” Other advantages include no extra load on the suspension, no deterioration in dynamics. The crew needs only a driver and an operator. All equipment can be removed and left in the garage. There’s no need to register changes in the vehicle’s design.

The only downsides are a limited choice of angles, blocked access to the trunk, and a less smooth, slightly less Hollywood-quality picture because the spring pantograph and Ronin handle vibration well but can’t completely overcome their own slow vertical sway. But otherwise, why not a replacement for the “Russian arm”?

I also enjoyed driving the Volvo; this vehicle knows how to charm. It has a cozy rounded design and a similarly rounded character. The XC90’s habits somewhat resemble a yacht—apparently, this trait was passed down from Yamaha’s DNA, which produced the V8 engine.

The rare layout of eight cylinders across the bay and high boosting is a Volvo hallmark. From a 4.4-liter volume, it managed to extract 315 hp, comparable to the BMW atmospherics of the same era. But this power is isolated from the driver. The sound is muffled, the throttle responses are smoothed. According to the stopwatch, the Volvo is a second slower than the Mercedes (7.9 s to 100 km/h on the best attempt), but for it, this is clearly not a competition in its sport.

Catching up with the filming vehicle and hanging centimeters from its bumper is not entertainment for the XC90, but work. And for the driver too. To achieve precise traction control, you need to use the manual mode of the “automatic.”

However, the suspension here is lively, comfortable, and will likely remain so for a long time. Nevertheless, the XC90 V8 has plenty of other features that unpleasantly surprise owners in terms of reliability. So I wouldn’t venture to say which of the two film crane vehicles is cheaper to maintain.

But I do know that as a camera car, the XC90 with its tail-suspension successfully performs 90% of the tasks for automotive video shooting at a level sufficient to impress the average viewer in a short clip. And the Russian Arm is necessary when shooting big cinema for the wide screen with a serious budget and a need for complex, but perfect, imagery. That’s essentially the difference between YouTube and Hollywood.

Photo: wikipedia.org | Dmitry Pitersky

This is a translation. You can read the original article here: Моторы закадра: ездим на кинокранах Mercedes-Benz ML 63 AMG и Volvo XC90 V8

Published October 10, 2024 • 14m to read